In 1948 James Baldwin left Harlem and New York for Paris, following in a long line of talented African Americans who hoped to experience life free of the terrible burden of racial prejudice and injustice.

Like Richard Wright before him, James Baldwin went to Paris, as he put it, to “cheat the destruction” which faced him as a black man in America. He left because he wanted to “be and honest man and a good writer.” But as he worked on books such as “Go Tell it on the Mountain,” “The Amen Corner” and “Notes of a Native Son,” works focused on his life back home, he began to realize that what he needed to do more than anything else to achieve his goal was to participate directly in the struggle for racial justice. Once he realized this he was “released from the illusion that I hated America,” and he returned home after nine years in Paris to claim his birthright. He would no longer be an expatriate turning his back on the agonies of his country; he would use his particular talents and powers to proclaim to his people — black and white — that, like it or not, they were all “brothers” and that they needed to make that fact the focus of the struggle. In the great 1962 essay, “Down at the Cross,” included in “The Fire Next Time” he spoke like a biblical prophet, calling on “relatively conscious whites” and “relatively conscious blacks” to act like lovers by coaxing out the consciousness of their countrymen and in so doing “end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country.” The essay was an immediate success. In 1961 Baldwin had published a collection of essays entitled “Nobody Knows My Name”; in May of 1963 his picture appeared on the cover of Time, and everyone knew his name.

Although Baldwin’s message was well-received by those who hoped the racial divide in America could be overcome, there were many who believed the divide was or should be permanent; these people had nothing good to say about someone who insisted on the “brotherhood” of all Americans.

For racist whites he was a man to be feared, a dangerous and all too articulate representative of the integrationist movement. To some blacks he was an “Uncle Tom,” all too willing to reach out to his oppressors. Caught in the middle, James Baldwin persevered. He never forgot that theories and ideologies change and that the individual must find “one’s own moral center and move through the world hoping that this center will guide one aright.” He continued to criticize his nation for its hypocrisy in regard to race but to call for unity, and gradually even his African American detractors began to receive his message. At his funeral in New York in 1987 Amiri Baraka, who had been a Baldwin critic, now recognized him as “God’s black revolutionary mouth.”

BY DAVID LEEMING

About David Leeming

David Leeming received his B.A. in English from Princeton University in 1958 and his Ph.D. in Comparative Literature in 1970 from New York University, where his dissertation, under the direction of Leon Edel, was on Henry James and the French Novelists.

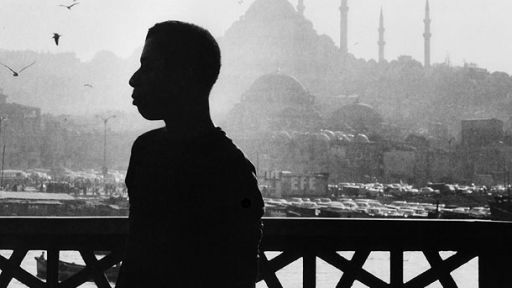

Following his graduation from Princeton, Leeming taught at Robert College in Istanbul for eight years. He met James Baldwin there in 1961. Later, during his graduate school years in New York, he worked as Baldwin’s personal assistant, sorting and filing papers, attending to correspondence, and doing speech research. In 1965 he accompanied Baldwin back to Istanbul where, with Baldwin’s younger brother David, they lived for a year. During that time Baldwin completed Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, a novel which he dedicated to Leeming and to his brother David. Leeming maintained his friendship with Baldwin during the years that followed. The two exchanged many visits: in Amherst, Massachusetts, where Baldwin often taught in the 1980s; in London, when their paths crossed; in Connecticut, where Leeming lived with his wife and children; and in St. Paul de Vence, France, where Baldwin lived for part of each year. Leeming spent the last days of Baldwin’s life in St. Paul de Vence, where he helped David Baldwin care for his brother.

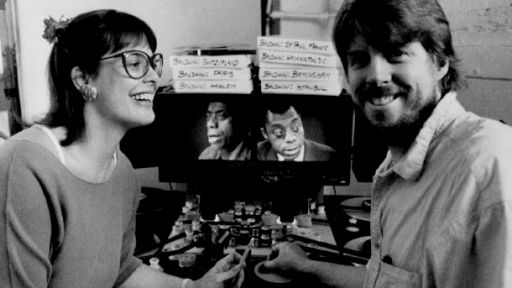

Read more about Leeming on the official film page of James Baldwin: The Price of a Ticket.