TRANSCRIPT

♪♪ ♪♪ -There are days -- this is one of them... ...when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it.

From my point of view, no label, no slogan, no party, and no skin color, and, indeed, no religion, is more important than the human being.

-Now, when you were starting out as a writer, you were Black, impoverished, homosexual.

You must have said to yourself, "Gee, how disadvantaged can I get?"

-No, I thought I hit the jackpot.

-Oh, great.

[ Laughter ] -It was so outrageous, you could not go any further, you know.

[ Laughter ] So you had to find a way to use it.

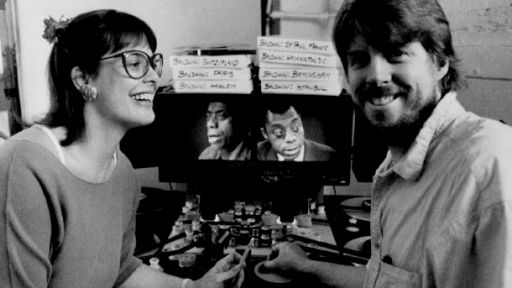

-♪ Sometimes I feel ♪ ♪ Like a motherless child ♪ ♪ Sometimes I feel ♪ ♪ Like a motherless child ♪ ♪ Sometimes I feel ♪ ♪ Like a motherless child ♪ ♪ A long way ♪ ♪ From home ♪ [ Drumbeat ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Sobbing ] [ Continues sobbing ] -I first met Jim when he and I and the world were young enough to believe ourselves independently salvageable.

We became friends in the late '50s, just as the United States was poised to make its quantum leap into the future; just as Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and other Southerners were girding themselves for the second civil war in one hundred years; and just when Malcolm X was giving voice to the anger in the streets and in the minds of Northern Black city folks.

In that riotous pulse of political fervor, James Baldwin and I met again and liked each other.

In this particular society... ...we are supposed to be so contained.

Men are supposed to be men, women are supposed to be women, and not need, really need, anybody else.

The ability to ask, "Will you be my brother?

", the courage to ask, is often missing.

James Baldwin was a brother.

Incredible!

-He lived his life as witness.

He wrote until the end.

We hear of the writer's blocks of celebrated Americans, how great they are, so great, indeed, that their writing fingers have been turned to checks.

But Jimmy wrote.

He produced, he spoke, he sang, no matter the odds.

He remained man and spirit and voice ever-expanding and ever more conscious.

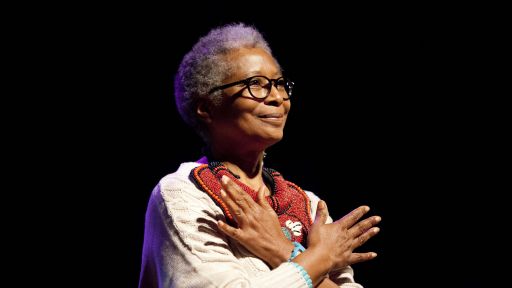

[ Applause ] Let us hold him in our hearts and minds.

Let us make him a part of our invincible Black souls, the intelligence of our transcendence.

Let our Black hearts grow big, world-absorbing eyes like his, never closed.

Let us one day be able to celebrate him like he must be celebrated, if we are ever truly to be self-determining.

For Jimmy was God's Black revolutionary mouth -- if there is a God -- and revolution his righteous natural expression.

[ Applause ] ♪♪ [ Mellow jazz plays ] ♪♪ ♪♪ -I was born in Harlem in 1924 when it was a very different place than it is now.

My father came from New Orleans, my mother came from Maryland, and if they had waited, you know, two more seconds, I might have been born in the South.

The first house I remember was on Park Avenue, which is not the American Park Avenue.

Or maybe it is the American Park Avenue.

-Uptown Park Avenue.

-Uptown Park Avenue, where the railroad tracks are.

We used to play on the roof, and I can't call it an alley, but near the river, there was a kind of dump -- garbage dump.

That was the first -- Those were the first scenes I remember.

I remember my father had trouble keeping us alive.

There were nine of us, and I was the oldest.

So I took care of the kids and dealt with Daddy, whom I understand much better now.

Part of his problem was, he couldn't feed his kids.

But I was a kid, and I didn't know that.

And he was very religious, very rigid.

In fact, in a word, he wanted power.

He wanted Negroes to do, in effect, what he imagined White people did -- that is to have -- to own the houses, to own U.S. Steel.

And this is what, in effect, killed him.

Because there was something in him which could not bend.

He could only be broken.

[ Soft, dramatic music plays ] ♪♪ You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world.

But then you read.

It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me the most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.

♪♪ I went to the 135th Street library at least three or four times a week, and I read everything there.

I mean, every single book in that library.

♪♪ In some blind and instinctive way, I knew that what was happening in those books was also happening all around me.

And I was trying to make a connection between the books and the life I saw and the life I lived.

[ Children playing ] I knew I was Black, of course, but I also knew I was smart.

I didn't know how I would use my mind, or even if I could, but that was the only thing I had to use, and I was going to get whatever I wanted that way, and I was going to get my revenge that way.

So I watched school the way I watched the streets, because part of the answer was there.

-He did a play, when I was very, very small.

He had to be very small himself.

He must have been about 8 or 9 years old when he wrote his first play.

And he also wrote the school song, which they used until the school closed down.

The whole family went to this school, P.S.

24, 128th St. between Fifth and Madison, and everyone had to sing this same song.

If I can remember, let's see.

♪ Farewell, farewell to 24 ♪ ♪ We shall miss you evermore ♪ ♪ We hate to say goodbye to you ♪ ♪ That's what we all must know ♪ ♪ To teachers, we must say goodbye ♪ ♪ And to our friends, oh, my, oh, my ♪ ♪ We grieve to say we're very sad ♪ ♪ But going forward is a thought to make us glad ♪ ♪ Tuh-dum tuh-dum tuh-dum tuh-dum ♪ And this is something, you know, we all went through.

And [Laughs] it was one of the things, I guess, that you never forget.

-By the time I was 14, I knew I wanted to be a writer.

And I wrote all the time.

I wrote at first on paper bags.

I wrote plays and poetry and stories, and writing was my great consolation.

My father was very opposed to it, very frightened by it, and that frightened me.

My mother was frightened -- was frightened, too, but my mother was another kind of person.

She didn't try to stop me.

-Did you think he was going to be as big a success and as important?

-No, no, I didn't think that.

But I knew that he had to write.

-I-I got something from school today, and Mom said I should show you.

-Hmm.

History of New York, huh?

-I-I wrote it over and over again, and I had to read a lot of books about it.

-It might have been nice if you had written something about the Bible.

Something about your own people and God.

-I will, next time, sir.

I'll tell you this: My father frightened me so badly, I had to fight him so hard, that nobody has ever frightened me since.

And I went into the church, partly because I had been driven there all my life, and my father had always determined that I would be a preacher, I'd always said I wouldn't be, but life outwitted me, you know, and corroborated him, because at that point in my life, there was no place for me to go.

I had no intention, ever, of becoming a preacher or of entering that terrifying church that I'd spent nearly 14 years, by that time, trying to get out of.

But I was so afraid of everything else, that in a way, I ended up with the devil I knew, though I couldn't have said it then.

[ Gospel music plays ] -♪ Jesus ♪ ♪ Jesus ♪ ♪ It's alright ♪ ♪ It's alright ♪ ♪ In the morning ♪ ♪ Late at night ♪ ♪ Midnight ♪ ♪ We have no prayer ♪ -Hey, man, you don't have to have no title behind your name just to go tell somebody Jesus loves you.

You don't have to have a title behind your name to say, "Jesus saves," that Jesus delivers, that he's set free today!

-Hallelujah!

-Praise the Lord.

-But you got to take what he's giving you and put it to good use.

-Amen.

-You can go to school all you want to, get all kind of D.D.s or Ph.Ds or whatever else you want behind your name, but if you don't take that and put it to good use, it's worthless.

-Amen.

-The whole question of Jimmy and religion is a knotty question, it's a difficult question.

It's one that as a biographer, obviously, I have to deal with, and I haven't really finished dealing with it.

I think it's important to realize that, rhetorically, the church is extremely important to Jimmy, the language of the church, the language of the Bible primarily, the patterns of the Bible, even the struggles of the Bible.

-I had been a boy preacher for three years.

And those three years, really, in a sense, you know -- those three years in the pulpit, I didn't realize it then, that is what turned me into a writer, really.

Dealing with all that anguish and that despair and that beauty for those three years.

And I left because I didn't want to cheat my congregation.

I knew I didn't know anything at all.

And I couldn't leave -- If I'd left the pulpit, I had to leave home.

So I left the pulpit and I left home in the same day.

That was quite a day.

[ Chuckles ] And, uh, well, in a sense, I became a writer because I thought if I got through, my old man would be proud of me.

You know?

I started writing when I was very, very, very young.

I started being published when I was 22.

And once I was out of Harlem, I began to see -- Well, I was a book reviewer, you know?

I wrote some of the early, early essays in that time.

But I had written myself into a wall.

I was -- You know, I was -- I was expected to write about one subject only.

So, for two years, I reviewed all those post-war "Be kind to colored people," "Be kind to Jews" books.

All 47,000 of them came across my desk.

And [Chuckles] I simply had to go, you know, and try to figure what in the world was happening to me.

Negroes were not served here, Negroes cannot eat there.

If you were a Negro, there was nothing you could do at all.

And one evening, something happened to me which was -- which has frightened me ever since.

And it was simply that I walked into a restaurant where I knew I would not be served.

But I walked in with the determination to be served or to die.

And I waited, I wasn't served, of course.

The woman said -- poor little girl -- said that Negroes were not served here, and I wanted to kill her, but I couldn't get close enough to her, so I threw a glass a water at her.

And when the glass of water hit the mirror behind the bar, I woke up.

It was a terrible turning point in my life.

[ Whoosh ] [ Glass shatters ] I never forgot it, because it was the first time in my life that I ever wanted, really, to hurt anybody.

And that drove me, finally, out of the country.

[ Soft music plays ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ The best thing I ever did with my life, I think, was, in effect, flee America and go to Paris in 1948.

And it gave me time to vomit up a great deal, a great deal of bitterness.

♪♪ At least, I could operate in Paris without being menaced socially.

No one cared what I did.

-I met Jimmy in '49, in Paris.

Uh...

I was 17, he was 24.

We were both kids in the streets.

No money.

And we became friends.

-Everybody was poor in Paris.

Those who worked were poor.

Jimmy was very poor, and he was living in a cheap hotel on the Left Bank.

He'd move around.

He loved to give parties.

Loved to invite people in, and he didn't spend a lot of money on them.

People would just -- just come just to be -- just to be there.

[ Mid-tempo music plays ] And even then, when we were young, we use to break up bars and drink all night long.

♪♪ We would sit up at night, dance and sing and laugh until 5:00 or 6:00 in the morning, and the neighbors would say "We heard you, but you didn't bother us."

-All our time, all our life was ours.

I mean, we had no job, nothing else to do than live.

And he lived.

My God, he lived.

Me too, I lived.

We went around the streets, drinking, a lot already.

I heard also about the complaints about that, but, you know, we could drink.

We both could drink very well.

[ Chuckles ] Very well.

I used to see him every day, we would talk, usually all night, and, uh, we were in love with each other, you know, Being two young kids, both in different ways lost.

I was a very lost kid, and he was certainly, but another way -- a completely different way.

-He said that he came because he wanted to be a writer, and he couldn't be a writer in America.

It was that simple.

-It was very significant.

The first thing I wrote in Paris, once I caught my breath, was "Everybody's Protest Novel," you know, to get that behind me and to find out what I could really do, you know, if I really was a writer instead of a pamphleteer.

-I think the next thing that really was impressed on me, because I had been reading some things, was "Notes of a Native Son."

When that book came out, it impressed me because a young Black man, you know, whose picture looked like he was earnest and serious about what he was saying, and I think he was impressive on a whole generation of Black people, not just writers.

-I mean, he never lost sight of the fact that he was an American.

He always considered himself very much an American, even in -- you can see that in his early essays, the "Notes of a Native Son" essays, in which really he is using Paris, using France, as a means of discovering his own identity.

-I was very lucky.

The first thing I realized in Paris was that you don't ever leave home.

You take your home with you.

You better.

You know?

Otherwise, you're homeless.

-France was not without its race prejudices.

It simply didn't have any guilt vis-à-vis Black Americans.

And Black Americans who went there, from Richard Wright to Sidney Bechet, were so colorful and so talented and so marvelous and so exotic, who wouldn't want them?

Of course.

But among the people they did not want in France were the Algerians.

As Jimmy said, they were the niggers of France.

To him, they were his brothers.

He was very outspoken during the Algerian War, when they were trying to win their freedom from France in the '50s.

He wrote about the Algerians in this excerpt from "No Name in the Street."

"I had come to Paris with no money, and this meant that in those early years, I lived mainly among les misérables.

And in Paris, les misérables are Algerian.

They scraped such sustenance as they could off the filthy, unyielding stones of Paris.

The French called them lazy, but they were not lazy.

They were mostly unable to find work.

And their rooms were freezing.

And although they spoke French, and had been, in a sense, produced by France, they were no more at home in Paris than I."

[ Indistinct shouting ] James Baldwin was relentless in his insight.

He knew where he was.

[ Indistinct conversations ] -The problem with him was that he needed quiet.

He loved the streets.

But he had to get out of the streets once in a while and get off someplace where he could work.

He was -- He was -- He was moving all the time, to find places where he could work.

-So we went to Switzerland.

I had that idea to go to Switzerland, where he would have a house of his own and nothing else to do in that village.

That I knew.

There was nothing else.

There was all snow, all mountains, so there was nothing else but just work.

I mean, it's life like 10 centuries ago.

Now it has changed a lot, but at that time, it was a lost village, really -- nothing else but snow, mountains, a few cows, and people.

It's true that, uh, we must have been a very strange couple, that's true.

A very strange couple in that village.

[ Chuckles ] Well, what can you do?

C'est la vie.

He'd be writing.

I would go do the shopping.

I would take him out again, after the work, have drinks, and have fun.

It was a very strange experience, but mostly for the people of the village.

But then that's how we learned about the first reaction of people towards a Black man, and these reactions come from a whole culture.

And that's in his essay, "Stranger in the Village."

There, he lived all that winter, and it was a fabulous experience for him, you know, in a whole, I mean, white village, all white.

The snow, mountains, everything was white.

A lot of children.

That, he loved.

The children adored him, and they loved him, and he loved the children, and we went along very well.

I mean, Jimmy -- I guess he charmed them, really.

[ Chuckles ] We had a marvelous winter.

He did his work, and how well.

And that's where he finished his first novel, "Go Tell It on the Mountain," okay?

-It's true, in that chalet, in the snow, I listened to Bessie Smith and to Fats Waller, and they carried me back to what I myself had been like when I was a little boy and gave me the key to the language which gave me "Go Tell It on the Mountain."

[ Child giggles ] -Because of the sound of the typewriter, I remember when he finished the novel, because he typed, you know, "The End."

You know, bing, bing, very slowly, with hitting, you know, very strongly.

Then, I think I came out of the kitchen, I said "Eh, bien, mon vieux, je crois que c'est fini."

And he said "Yes, it's the end!"

So we got out, we had a lotta, lotta drinks.

Okay?

We got drunk, and that was it.

But then we came down to the valley, put that novel on the mail, and it was published, obviously.

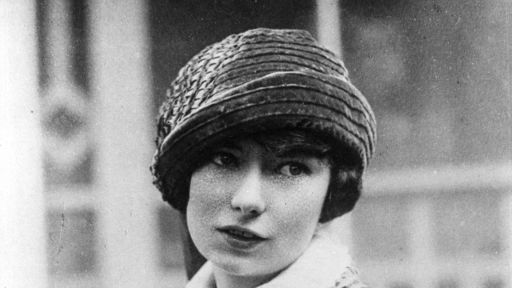

[ Chuckles ] -Well, in 1948, I was the publicity director of Knopf, Alfred Knopf, the publisher.

And sounds grand, but it was $75 a week then, however.

And I read a lot of magazines in the course of doing publicity.

And I read these marvelous pieces by a James Baldwin.

First, in "Commentary" magazine, a piece about Harlem.

And then a few pieces in "The New Leader," which is sort of a Trotskyite I guess, magazine of the times.

Still going.

And they were so wonderful, these pieces, that I went to the editor-in-chief, named Harold Strauss, and I said, "Harold, look at this.

This is a wonderful writer.

He's concise, he's powerful, he's witty, and he's saying something, and you should get after him."

I wasn't doing any editing then.

And Harold said, "Oh, thank you," and he read the pieces.

He said they were very nice.

He liked them very much, and he knew the woman who was Jimmy's agent then, who's also named Strauss -- Helen Strauss, no relation whatsoever.

And Helen said, "Yes, Jimmy's working on a novel, and I'll send it over to you."

And eventually, Harold got this bale of a manuscript in all different size pages and different typewriters obviously used on it over the course of the years.

And he looked -- he read some of it, and he called me in and he said, "I don't like this kind of book, Bill.

It's not a real straightforward narrative novel, you know.

Would you look at it?"

And so I took it home in here, this very apartment.

And I read it, and I thought, "My God, this is a big book.

This is important."

And I took it in, back to the office.

And two other editors read it and agreed with me, said it was a wonderful book.

And we did it.

-And I think this is an autobiographical novel.

You know, he wrote these confessionals, he wrote a lot of autobiographical work, explaining what it is to grow up in Harlem.

I'm gonna give an example of this excellent scene here with -- and notice the detail, and the economy of this passage.

Okay?

And this is Sunday morning in church.

Okay, now get this: "The sisters in white, heads raised.

The brothers in blue, heads back.

The white caps of the women seeming to glow in the charged air, like crowns.

The kinky gleaming heads of men seeming to be lifted up.

And the rustling and the whispering ceased.

And the children were quiet.

Perhaps someone coughed, or the sound of a car horn or a curse from the streets came in.

Then, Elijah hit the keys, beginning at once to sing, and everybody joined him."

[ Piano plays softly ] -♪ Precious Lord ♪ ♪ Take my hand ♪ ♪ And lead me on ♪ ♪♪ -Baldwin's idea was that Christianity could expand and include more people, even Whites.

You notice in "Go Tell It on the Mountain," the father believes that Whites are irredeemable.

-[ Scoffs ] When the White man start giving us prizes, I've got to ask myself, "What is he after?"

White man's been our torment for over a hundred years.

Anything he do, everything he tries is a way of beating us down, keeping us small.

[ Sighs ] You don't believe me, do you?

[ Sighs ] -How can I put this?

The Baptist church in which I grew up, in all but actual fact, you know, in all but actual vocabulary, assumed that all the saved were Black and all the doomed were White.

It was a kind of, um, fantasy revenge.

And it was also, very importantly, a way of getting them from one day to another, through their lives, and as it turns out, through generations.

But, you know, times do change.

-Well, I was very excited about it, and I was pushing it in all directions, but it didn't get great reviews.

It got nice reviews.

They were okay, but not fantastic.

The "Times" was disappointing, as I remember.

That's the most important place to have a review.

And hardly a dog barked, as they say in England, when the book came out.

But it was -- And it sold reasonably well.

But, of course, later on, it went on to sell millions in various paperback editions and be adopted at school courses and so on.

But Jimmy -- little Jimmy then didn't know that.

I hear Baldwin as a part of the continuity, begun, if you will, for me anyway, with Frederick Douglass in 1849 in the slave narrative.

I hear his voice.

I hear Baldwin when I think of Jupiter Hammon, a slave in the 18th century.

I hear Baldwin in the music -- the lyric, really -- of George Moses Horton, a Black slave writing about 1840, '50.

He wrote, "Alas, and was I born for this, to wear this slavish chain."

I hear Baldwin.

-After "Go Tell It on the Mountain" was published, he wrote me in 19-- It would be 19-- January of '54, that he has a project, and said, "It's a great departure for me, and it makes me rather nervous.

It's not about Negroes, first of all.

Its locale is the American colony in Paris.

What is really delicate about it is that since I want to convey something about the kinds of American loneliness, I must use the most ordinary type of American I can find.

The good White Protestant is the image I want to use.

This is precisely the kind of American about whose setting I know the least.

Whether this will be enough to create a real human being, only time will tell.

It's a love story, short, and -- wouldn't you know it -- tragic.

Our American boy comes to Europe, finds something, loses it, and in his acceptance of his loss, becomes, to my mind, heroic.

It's called 'Deep Secret: One for My Baby.'"

Well, it wasn't called "One for my Baby."

It was called "Giovanni's Room," eventually.

And he finished it and sent it to his agent, who gave it to Knopf.

And wouldn't you know, I was on vacation when it came in -- when the manuscript came in.

And the two editors who had worked on "Go Tell It" read it, and I guess they were scared.

They were scared about the -- Homosexuality was the theme, and that was not on the books in those days.

There was very little written about homosexuality -- certainly very few novels -- And they turned it down.

And when I got back from vacation, I was horrified, but it was gone by that time.

Gone back to the agent, who was peddling it to somebody else.

-Jimmy Baldwin was neither in the closet about his homosexuality, nor was he running around proclaiming, you know, homosexuality.

I mean, he was what he was.

And you either had to buy that or, you know, mea culpa, go somewhere else.

-I think the trick is to say "yes" to life.

I think the details -- It's only we, at 20th century, which is so obsessed with the particular details of anybody's sex life.

I don't think those details make any difference, and I will never be able to deny a certain power that I have had to deal with, which has dealt with me, which is called love.

And love comes in very strange packages.

I loved a few men, I loved a few women.

And a few people have loved me.

That's, I suppose, all that saved my life.

-"Giovanni's Room" had some pretty good reviews, and it sold probably better than "Go Tell It," originally.

I remember, there was one review by Nelson Algren, who is himself a magnificent novelist, in "The Nation," and he said at the end of it, "This novel is more than another report on homosexuality.

It is the story of a man who could not make up his mind, one who could not say 'yes' to life.

It is a glimpse into the special hell of Genet --" that would be Jean Genet, the French homosexual writer -- "told with a driving intensity, its horror sustained all the way."

That's good stuff.

-You published "Giovanni's Room" very early on.

-I finished the book in '55 or '56.

-And that, to deal with homosexuality, was difficult.

-Yes.

-And you already were dealing with, you know, Black writer.

-Mm-hmm.

-What made you decide to do that?

-Well, one could say, almost, that I didn't have an awful lot of choice.

"Giovanni's Room" comes out of something which tormented and frightened me, the question of my own sexuality.

It also simplified my life in another way, because it meant that I had no secrets.

Nobody could blackmail me.

You know, you didn't tell me; I told you.

[ Soft jazz plays ] ♪♪ -Jimmy Baldwin went to France to write.

He tried to go somewhere where he was secluded and removed.

And he liked France.

You know, more American artists need to be able to see the rest of the world, as well as participate in the social development of the United States, because it broadens their perspective.

-Well, the French left him alone and allowed him his space, his corner, and what he needed most.

And when he returned, one could see the difference immediately.

There was a difference in me also.

I'd grown older.

And he was a man, and I was a young man.

We could now share something -- something we hadn't before.

We could drink together, we could sort of talk together, you know.

You know, there was a -- oh, a vast amount of difference between the man who -- the young man who left And the old man who returned.

And it has nothing to do with age.

[ Up-tempo music plays ] ♪♪ We became closer and closer.

And perhaps it was that moment when two brothers could sit and talk to one another, and talk, you know, about each other's lives, and what we felt, what we believed in.

[ Soft music plays ] -I met Jimmy in New York.

I suspect it was the late '50s.

He was going to some of the same literary parties that I was going to.

And Bob Silvers, he buttonholed me at a party one day and said, "Well, Jimmy is in bad trouble financially.

He's trying to write a book.

Um, he's -- He's really hard-up.

He has to support a lot of his family.

I know you have a guest house up in Connecticut.

Would it be a possibility, maybe, to take Jimmy in?

He needs a place to write."

"Another Country" was the book that Jimmy was writing at that time.

He was suffering over it.

He would come over here to this house from the guest house where he was working, And -- And I think he -- It may have been the first book as I recollect, in which he said, "I am not really in total command of what I'm trying to do."

-There were times he'd come in and say, for instance, "This person is not speaking to me today.

I don't know what's the matter with him.

I haven't done anything wrong."

And I'd say, "Well, stay with them, you know.

Go ask them how they feel, how they're feeling."

We talked about his characters, just the way I'm talking.

He'd ask me and come in and say, "Well, how are you feeling?"

and I would ask about them that way, you know.

"How are they this morning?

What are they doing?

Have they left the bar yet?

Are they still drinking themself to death?"

Or whatever.

Something like that, you know.

-He labored all that winter, and I might say, with a great deal of conflict because the subject was quite bold and really quite daring.

It had to do with Blacks and Whites, with their relationships -- intimate relationships.

And maybe he felt that he was on uncertain ground.

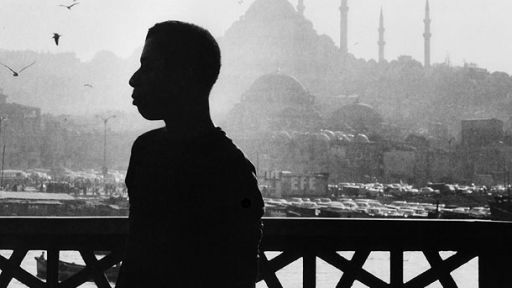

[ Soft Middle Eastern music plays ] ♪♪ So Jimmy escaped the problem by going to Turkey, of all places, where he had been invited by a friend who -- a Turkish actor whom he had met in New York.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Muezzin chanting ] -There is something -- there is something in this land -- there is something ancient that Jimmy felt was as ancient as his African blood.

It's silly to say that he felt he was near his roots, but he felt he was near some roots as valid as his.

[ Mid-tempo Middle Eastern music plays ] ♪♪ The old city, it reminded him of Harlem, I think.

The people, the faces, the warmth, the smell, the crowds, the noise -- you know, everything.

[ Indistinct conversations ] He loved the book market.

It reminded him of his childhood days, perhaps, in Harlem.

♪♪ ♪♪ -And when I was living in Istanbul -- I don't want to be romantic about poverty, because it's not pretty -- nevertheless, the Turks, the people I was dealing with who had nothing, reminded me of the people I grew up with who had nothing, who would give you anything, really.

The shirt off their back, money, bread.

♪♪ -The first time I met Jimmy was in December of 1961.

I was teaching at Robert College in Istanbul, and he was staying with his friends Engin Cezzar and Gulriz Sururi.

I went to a party at their place, and someone said, "Why don't you go into the kitchen to meet Jimmy?

He wants to see what Americans in Istanbul are like."

And there was a lot of laughter about that.

And I went in, and there was this rather astounding-looking man sitting at a kitchen counter.

And he made a kind of flourish with the pen on the paper.

And he turned around and he said, "It's finished, baby."

And those are the first words he said to me.

And then I introduced myself, and I said, "What's finished?"

And he said, "'Another Country' is finished."

So, he had just finished it the moment I walked into the room.

-In this passage from "Another Country," a White character in a taxi is riding through Harlem.

He's talking about his best friend, a Black friend, who has died, and he speaks of the Black family's reaction to his presence.

"I walked into that house, and they were just sitting there, Ida and her mother and her father, and there were some other people there, relatives maybe, and friends.

I don't know.

No one really spoke to me, except Ida, and she really didn't say much.

And they all looked at me as though -- well, as though I had done it.

And, oh, I wanted so badly to take that girl into my arms and kiss that look off her face and make her know I didn't do it, I wouldn't do it.

Whoever was doing it was doing it to me, too."

"Another Country" is about Blacks and Whites trying to connect, trying to respect each other, trying desperately to love each other.

-If everyone had been in love, they'd treat their children differently, they'd treat each other differently.

-Yes, well, but perhaps that is one of the points in "Another Country," which, it seems to me, is as much about love as about anything else.

-It is about love.

-It is more, it is more.

-It's about the price of love, too.

-Which is the price of life.

-Yes, but people don't seem to realize that.

[ Indistinct conversations ] -Much to Jimmy's surprise, "Another Country" turned out to be his most successful book yet.

It was on "The New York Times" best-seller list for weeks and weeks.

It was even translated into more than two dozen languages.

And that, of course, made Jimmy very happy, most especially because it would make it possible for Yashar Kemal, his great friend, to read the book.

-[ Speaking native language ] -Jimmy loved a good rousing discussion.

I remember one time when he was living in this house, I said to him "Why do you let so many people come into the house?

So, why do we spend so much time eating and drinking and staying up late when you're trying to write a novel?"

And he said to me, "If I didn't live that way, I couldn't write the novel.

If I lived a safe, quiet life, I wouldn't be living life.

Therefore, you just have to put up with the people around and the noise and the drinking, the staying up late."

[ Up-tempo music plays ] But always, at the end of the evening, although one wondered how anybody could have worked at that point, he would sit up and write until, what shall I say, late in the morning.

[ Soft jazz plays ] ♪♪ ♪♪ -It sort of -- it was, anyway -- kind of a place to rest and to work, because I couldn't live in Paris anymore, and New York is impossible.

And it was, in some ways, another way of life, another set of assumptions which are not -- are not mine, or, you know, not -- which I didn't grow up with, because I'm not a Muslim, but which can teach you a great deal about your own set of assumptions because they are -- once you find yourself in another civilization, you're forced to examine your own.

[ Waves lapping shore ] -♪ We shall overcome ♪ ♪ We shall overcome ♪ ♪ We shall overcome some day ♪ -Even though he may have been skeptical about the Kennedys, he felt that he really had to come back and be part of what was happening in America.

It would have been just impossible for him to sit in France or Turkey while this very important movement was taking place in his own country.

-♪ Oh, just like a tree ♪ ♪ That's planted by the water ♪ -♪ Oh, oh, oh ♪ -♪ We ♪ -♪ We shall not be ♪ -♪ We shall not be moved ♪ -♪ Oh, we ♪ -When Dorothy Counts was spat on by the mob, when she was trying to go to school, that was when I decided I was coming home.

And I came home, you know, to see, you know, to do whatever I could do.

-♪ Just like a tree ♪ ♪ That's planted by the water ♪ -♪ Oh, oh, oh ♪ -♪ We shall not ♪ -And I went South, and I began to deal with a reality which had always been incipient in me but never been expressed or, you know, objectified.

I fell in love with those people.

And I was very happy to be South, even though it was very frightening.

Something in me -- Something in me recognized it.

Something in me had come home.

-You learn from the world you live in, brother.

-He's not even teaching me about the future of my people.

-What do you go to school for, then, dummy?

-We don't even have a country!

-I know that.

-Do we have a country?

-You say the United States is your country, which is not your country.

You have no flag, brother.

-A boy last week, he was 16, told me on television -- thank God we got him to talk -- maybe somebody will start to listen -- he said, "I got no country, I've got no flag."

Now, he's only 16 years old.

And I couldn't say, "You do."

I don't have any evidence to prove that he does.

-He was the person who had initially -- or one of the first people -- to cry out what we were feeling, and, in fact, what we were going to feel and what we were going to do.

He was one of the first to articulate it.

-And the moment you are born, since you don't know any better, every stick and stone and every face is White.

And since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose that you are, too.

It comes as a great shock, around the age of 5 or 6 or 7, to discover the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.

It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you.

[ Light laughter ] It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you.

-In that time that he was here, that I first began to see that terrific, almost schizoid, wrenching that he suffered.

Being pulled in one direction by the demands of his art, and the other direction by his moral need to do what he was also good at, which was to preach.

That is, to preach the Gospel of equality, to preach the Gospel of revolution, if you want to call it that.

-He once said that he left the pulpit in order to preach the Gospel, and in a certain sense, that's true.

This was something he could do.

You could say this was God's gift to him, and this is what he made use of.

-He had begun to make notes for the work that later became "The Fire Next Time" while he was here, and discussed it with me -- discussed the need to write an essay -- a long polemical essay to tell White Americans what it was like to be Black.

-"Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands.

We have no right to assume otherwise.

If we -- and now I mean the relatively conscious Whites and the relatively conscious Blacks -- if we do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and change the history of the world.

If we do not dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, re-created from the Bible in songs by former slaves, is upon us.

'God gave Noah the rainbow sign.

No more water.

Fire next time.'"

-Did you have any idea that this was going to be a kind of live grenade, tossed -- at least, into the White world?

-It didn't occur to me at all.

Isn't that funny?

Not at all.

I wrote it as a kind of -- as I repeat, a kind of plea to Black people and to White people about this country.

-What he did was to write it in a language that fairly educated, White middle-class people could understand.

And I think he led many of them to change their ways, to become more sympathetic to civil rights.

-Many people, including myself, believe it's one of the great documents of the 20th century.

He was becoming very distinctly one of the most -- certainly, if not the most -- eloquent early spokesmen for the Black movement.

-I don't know what most White people in this country feel.

I can only conclude what they feel from the state of their institutions.

I don't know if White Christians hate Negroes or not, but I know that we have a Christian church which is White and a Christian church which is Black.

I know, as Malcolm X once put it, that the most segregated hour in American life is high noon on Sunday.

That says a great deal to me about a Christian nation.

It means that I can't afford to trust most White Christians, and certainly cannot trust the Christian church.

I don't know whether the labor unions and their bosses really hate me.

That doesn't matter, but I know I'm not in their unions.

I don't know if the real-estate lobby has anything against Black people, but I know the real-estate lobbies keep me in the ghetto.

I don't know if the Board of Education hates Black people, but I know the textbooks they give my children to read and the schools that we have to go to.

Now, this is the evidence.

You want me to make an act of faith, risking myself, my wife, my woman, my sister, my children on some idealism which you assure me exists in America which I have never seen.

-I never said that.

[ Applause ] -I think part of his disillusionment was that some of these people in New York weren't really liberals.

I mean, you know, Blacks were the first ones to attack liberalism.

-One of these liberal, well-intentioned people would say something like, "Uh, well, you don't mean, Jimmy, that -- that Black people might --" And he would interrupt and said, "Yes, baby, they gonna burn your house down."

-It's up to you.

As long as you think you're White, there's no hope for you.

As long as you think you're White, I'm going to be forced to think I'm Black.

-We can never be satisfied, as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating, "For Whites Only."

[ Cheers and applause ] No -- No, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.

[ Cheers and applause ] -Jimmy Baldwin was in the tradition.

People are always saying to me, for instance, "Why is your poetry, why is your play so political?"

But that's our tradition, you know.

Whether you're talking about Frederick Douglas or W.E.B.

DuBois or Zora Neale Hurston or, you know, Toni Morrison or Alice Walker, that's our tradition.

And why is it our tradition?

Because not only is it our tradition, even from Africa, to include society as the focus of art -- you see, as its principle focus -- the development of society -- but as an oppressed people, we have no other choice but to fight.

-Do you feel the Broadway stage is a good place to get across your views on the race-relations question?

-Well, yes.

You know, but I don't -- I don't want to get into a long discussion of the American theater, which is another story.

But, yes, yes, yes, I do.

I'm very glad that we are opening on Broadway.

I hope it shakes up a few people.

♪♪ -Richard?

-Hmm?

-Richard, I want to help you.

I want to help you more then anything thing else in this world.

-How?

-Well, just like I used to.

I won't let you go anywhere without me.

-♪ Oh, if I could ♪ -Boy, you still determined to get your neck broke, huh?

-Yes.

Yes, well, it's neck-breaking time.

-By the time "Blue for Mister Charlie" came, Black people were not going to the theater, because there was nothing for them to go to the theater for, there was nothing they could identify with.

And their culture was not being explored in the theater, so I think perhaps what Jimmy meant, when he said there was no American theater, he meant there was no true American theater, because the American theater, as it was then, did not reflect him and his culture.

-Oh, morning, son.

-Mm-hmm.

-You up early.

Sleep well?

-Yeah, okay.

Boy, where you off to, looking so sharp?

Looks like you might be going to meet the man.

-[ Chuckles ] Going down to the mayor's office.

We're getting a biracial committee started.

-Oh, Daddy, why you knocking yourself out trying to have a cup of coffee with Mister Charlie?

He don't want you.

What you want with him?

-There's a whole lot more to it than that.

If you stick around here long enough, you'll see what I mean.

-Yeah, well, don't let me hold you up.

-Need anything downtown, Mama?

-Oh, no, thank you, son.

-Are you sure?

-Mm-hmm.

-How about you, son?

Need anything?

Like me to bring anything back for you?

-Well, there are a lot of things I need, Daddy, but I ain't too sure you could bring them back.

-Well... you certainly learned to be pretty insolent up North, didn't you?

Well, you just forget all that, son, and start remembering you're back home.

I'm still your father.

Yeah, and I can still knock you down.

-You gonna be late, Daddy.

-At least, before the civil rights movement, as long as they thought he was advocating a kind of, you know, Dr. King nonviolence, [Coughs] that was okay.

They could at least, you know, admit him to the edge of the pantheon marked "colored."

But, once "Blues for Mister Charlie" came out, he actually -- That play is about class struggle.

You know, there's a Dr. King character.

There's a Malcolm X character.

They're struggling for influence over the students, which is real life -- struggling for, you know, SNCC and the Carmichaels and the Rap Browns.

-The reason, perhaps, that "Blues for Mister Charlie" was considered such a terrible thing, you know, because this man was telling -- This man spoke the truth.

He spoke the truth.

I mean, he didn't pretty it up, he didn't color it up, he spoke the truth, the way it was, the way he saw it, the way he knew it.

That's perhaps why he was called a propagandist by many.

They just didn't want to deal with what he was saying.

-I've been dreaming of that day ever since I left here, dreaming of my Mama falling down the steps of that White man's hotel.

-Richard, she fell.

-No, Ma'am.

-The stairs were wet and slippery, and she fell.

-She was pushed.

-She fell!

-You saw the way they were always hanging around her, always around her 'cause she was pretty and Black.

-Now, Richard, you can't go through life believing that all the suffering in the world is caused by White people.

-Yeah, I can't?

Don't you tell me I can't.

They are responsible for all the misery I've ever seen.

That's good enough for me.

It's because my daddy ain't got no power that my Mama's dead.

And my Daddy ain't got no power, 'cause he's Black.

And the only way a Black man's is ever gonna get any power is to drive all them White people right into the sea.

-[ Gasps ] You gonna make yourself sick.

You gonna make yourself sick with hatred.

-I'm gonna make myself well with hatred.

-It can't be done.

It can never be done.

-Hmm.

-Hatred is a poison, Richard.

-Well, not for me, Grandmama.

-Mr. Baldwin, do you think you'll ever write anything that doesn't have a message?

-[ Chuckles ] -Assuming that there can be things written without a message.

-I don't quite know what that means.

In my view, no writer who ever lived could've written a line without a message.

You know, it depends on... What you're asking me, I think, is to what extent do I intend to become a polemicist or a propagandist.

Well, I can't answer that, because the nature of our situation has imposed on everybody involved in it things that one wouldn't ordinarily do, and you take risks which you wouldn't ordinarily take.

I don't think of myself as a public speaker or a civil rights leader or any of that.

But I'm not about to sit in some tower someplace cultivating my talent.

-It's not just a matter of letting go.

These privileges are part of you.

They're who you are.

It's right here in your gut!

-Then what is the point of all this struggling if Mister Charlie can't change?

-Who's Mister Charlie?

-You're Mister Charlie, Parnell.

All White men are Mister Charlie.

There's a little something you don't understand.

When you're a Black man with a Black son, you forget all about White people and everybody else and concentrate on trying to save your child.

That's why I let Richard go North.

Well, I failed.

Yeah, Lyle just walked him up the road and killed him.

-We don't know that Lyle killed him, and Lyle denies it.

-What do you mean, we don't know Lyle killed him?

-I mean we don't know!

We can just say it looks that way.

But, Meridian, circumstantial evidence can be a very tricky thing.

-When it involves a White man killing a Black man.

-The resolution of that play, where he says, you know, the preacher takes the gun -- this is the King character -- takes the gun and puts it in the pulpit and says "Well, I got the Bible and the gun.

One of these is gonna work."

You see?

That's another step forward.

And I think his writings since then, you know, demonstrated his coming to grips more and more and more clearly as an artist, and as, you know, a thinking human being and as an activist.

-That's why a play like "Blues for Mister Charlie" was not -- too much attention was not -- It was frightening.

It was frightening to see these things.

-My mama's afraid I'm pregnant.

[ Chuckles ] My mama's afraid of so much.

But I'm not afraid.

Oh, no, no, no.

I hope I am pregnant.

Yes, I hope I am.

One more illegitimate Black baby.

That's right, you jive mothers.

And I am going to raise my baby to be a man.

A man, do you hear me?

Oh, you let me be pregnant.

You let me be pregnant.

Don't let it all be gone.

Oh, Juanita, Juanita, you are going crazy.

Lord, don't you let me go mad.

You let me be pregnant!

Let me be pregnant!

[ Soft jazz plays ] ♪♪ -We don't teach you to turn the other cheek.

We don't teach you to turn the other cheek in the South, and we don't teach you to turn the other cheek in the North.

-Right!

-We teach you to obey the law.

We teach you to carry yourselves in a respectable way.

But at the same time, we teach you that anyone who puts his hand on you, do your best to see that he doesn't put it on anybody else.

[ Cheers and applause ] [ Gunshot ] [ Solemn music plays ] -Something happened to Jimmy when that assassination took place.

It was the long line of horrendous American assassinations.

♪♪ -I mean they're killing my friends.

It's as simple as that.

And have been, all the years that I've been alive.

For no reasons which, you know -- which have any validity.

[ Siren wails ] [ Hard rock 'n' roll plays ] ♪♪ -By the time we got to the mid-'60s, by the time things started to explode, a lot of criticism of Baldwin came.

Many of the people who were exploding had not read Jimmy Baldwin and, consequently, were very susceptible to the strong criticism that was clearly articulated in Eldridge Cleaver's "Soul on Ice."

Many of us equated the Black revolution with our manhood, with militancy, and masculinity.

And here was Eldridge Cleaver saying that Jimmy Baldwin hated his Blackness and hated his masculinity.

-And we've got to have enough self-respect to lay down our lives and to pick up the gun.

-Jimmy became a pariah.

Cleaver was representative of a raging, and quite logical, hatred... [ Siren wails ] ...on the part of Blacks for Whites.

[ Gunfire ] -There are days -- this is one of them -- when you wonder... what your role is in this country and what your future is in it.

-Jimmy was split by a love -- a desire for love and of communion, on the one hand; and on the other, by a kind of understanding that as long as the system existed as it did in this country, there could be no such getting together.

This sounds like a paradox.

But he loathed violence, and that is why he could never truly join the militants who rose in the 1960s.

-Not that you are willing to die -- not that you are willing to die but that you are willing to kill for your freedom!

-It is not a romantic matter.

It is the unalterable truth.

All men are brothers.

That's the bottom line.

If you can't take it from there, you can't take it at all.

♪♪ Love has never been a popular movement.

And no one's ever wanted, really, to be free.

The world is held together -- really, it is held together -- by the love and the passion of a very few people.

-Like anybody, I would like to live a long life.

Longevity has its place.

But I'm not concerned about that now.

I just want to do God's will.

-♪ Oh, oh ♪ ♪ Deep in my heart, yeah ♪ ♪ We do believe ♪ -Here is a letter Jimmy is writing from New York, dated the 12th of April, 1968.

"Dear Brother, between two or three weeks ago, I had to fly from Hollywood to New York to do a benefit with Martin at Carnegie Hall.

I did not have a suit, and had one fitted for me that afternoon."

"I wore the same suit at his funeral."

-♪ We shall be free someday ♪ ♪ Oh, oh ♪ -"What can I say to you, my dear?

Medgar, Malcolm, Martin -- murdered.

I really cannot talk, and yet I must."

[ Inhales deeply ] "Pray to those Gods who are not Western, who are not Christian, for our lives, for your brother's life.

I can't write anymore now.

Please understand.

My love will never change.

Your brother, Jimmy."

-Jimmy had moments when he came back from America, when he was very depressed, because he -- he lived in a very intense way there.

[ Soft jazz plays ] He hadn't been in good health for a while.

His heart had gone off, and they had to give him very serious treatments.

♪♪ He came to the South of France, and he spent months here, getting that together.

♪♪ And one day, he said, "Look, I'm going to buy this house."

He said that if it hadn't been for this place, he wouldn't be alive.

-This village, in a way -- in a big way -- saved his life, you know.

They looked after him.

They protected him in a way in which he couldn't be protected in America, let's say.

He finally had found a place where he could work.

You know, he found a place where he could sit and feel comfortable and at home.

Because to live that long -- and it takes you that long just to land -- you find yourself moving around the world.

You're writing on planes, you're writing in apartments, you're writing here and you're writing there, and then, finally, you find a place where you can come and write and live... and have friends, you know.

-Jimmy came here to my house a great deal for lunch and for dinner sometimes, and I went to his house for dinner.

His birthday party was always a great event for the entire South of France, it seemed.

And we often had lunch at the Colombe d'Or, which is like a family place for Jimmy.

He'd sit there for hours, not just with me but with all of his friends, Simone Signoret and her husband Yves Montand, and Nina Simone and Miles Davis, whoever was passing through.

He loved long, philosophical discussions.

We talked about the churches a lot in Harlem, and the music in the churches.

And sometimes we'd be full of red wine and sit down at the piano, and I'd knock out those songs.

And David and Jimmy and I and Bernard would sing "Hide Me in Thy Bosom" or "Have a Little Talk with Jesus," you see.

[ Laughs ] -♪ And we'll tell Him all about our troubles ♪ ♪ Hear our favorite cry ♪ -"Our favorite cry"?

-[ Laughs ] -Is it "feeble" or "favorite"?

-It's "feeble," you're right.

-♪ Hear our feeble cry ♪ ♪ Answer by and by ♪ ♪ Feel a little prayer wheel turnin' ♪ ♪ Feel a little fire a-burnin' ♪ ♪ A little talk with Jesus makes it right ♪ [ Music stops ] -What else now?

-Oh, my goodness, let's see.

-There was one you were thinking.

You went way back.

You and Jimmy went way back.

-I liked, uh... -♪ I'm singing in my soul ♪ ♪ Oh, I'm singin' in my soul ♪ ♪ When those trumpets blow ♪ ♪ I sing from morn till night ♪ ♪ It makes my burdens light ♪ ♪ I'm singing in my... ♪ [ Both laugh ] -Oh!

-Oh, I like that one.

[ Birds chirping ] -I'm not really, in America, a private person.

You know, I'm -- I'm a public person.

A public person cannot write.

Writers have always had to find -- and I'm not the only case, or even the most spectacular -- you have to find a way to do your work, because if you don't do your work, then you really are useless.

-You do spend a long time between novels.

Why is that?

-I'm that kind of writer.

There's no answer to that.

You know, everybody works the way he can work.

I must point out, though, too, that I have been working the last few years, between assassinations.

And that doesn't make it any easier either.

-He was working on "If Beale Street Could Talk," and he was -- It was the first novel he had written since America.

And that bothers him very much.

-It's a book that stands out from the other books.

It's a very bitter book.

And I think that's because he'd been disillusioned by what happened in the '60s, by the assassination of Malcolm X, the assassination of Martin Luther King.

You know, it's a very desperate period, and sort of like a post rev-- I would call it a post-revolutionary novel in which all the injustices remain, police brutality, and, uh, you almost feel as if the characters in that book are stalked like animals, like game.

-"I had certainly seen him before that particular afternoon, but he had been just another cop.

After that afternoon, he had red hair and blue eyes.

He was somewhere in his 30s.

He walked the way John Wayne walks, striding out to clean up the universe, and he believed all that.

Like his heroes, he was kind of pinheaded, heavy-gutted, big-assed, and his eyes were as blank as George Washington's eyes.

But I was beginning to learn something about the blankness of those eyes.

What I was learning was beginning to frighten me to death.

If you look steadily into that unblinking blue, into that pinpoint at the center of the eye, you discover a bottomless cruelty, a viciousness cold and icy.

In that eye, if you do not exist, you are lucky."

-Ah, people say Jimmy grew bitter.

[ Chuckles ] Put it this way to you -- you cannot go to a page and describe a human being in love or a human being in his pain if you are bitter.

-Bitterness is like cancer.

It eats upon the host.

Jimmy was not bitter.

What Jimmy was, was angry.

He was constantly -- He was angry at injustice, at ignorance, at exploitation, at stupidity, at vulgarity.

Yes, he was angry.

-What is it you want me to reconcile myself to?

I was born here almost 60 years ago.

I'm not going to live another 60 years.

You always told me it takes time.

It has taken my father's time, my mother's time, my uncle's time, my brothers' and my sisters' time, my nieces' and my nephews' time.

How much time do you want for your progress?

-Jimmy wouldn't let people off the hook, and some people are bothered by that.

And one way of handling the problem is to say, "Oh, his powers have slipped," you know.

[ Teletypewriter clacking ] [ Soft jazz plays ] ♪♪ -It's too bad that the public has to regard a writer of Jimmy's value and worth and contributions as somebody who was "in and out of vogue."

I don't think somebody who fought for human rights and dignity, the way Jimmy did, should be like last year's bow tie or this year's straw hat.

-What people tend to forget is that Jimmy spent a large part of his later years teaching, as well as writing.

He lectured all over the country.

He taught for several years in Amherst.

And this was very important to him.

-I thought he was a marvelous teacher and very invested and really cared that he was getting through to the students and that -- that there was that connection, that there was a dialogue going on.

One of the reasons that I think he decided to teach is that he wanted to be around young people who are getting the basis for their ideas.

And he was interested in what they were thinking.

-Well, I was fortunate.

My whole senior year I got to spend basically on James Baldwin's knee.

He would give us assignments, we would do writing, and then we would come in and read to each other.

Because Jimmy was so busy, because he was on the road while he was teaching the course, he would always take the class out for drinks afterwards because this is how he could get to know his students.

We hung out, and, you know, we laughed, and that's how our friendship started.

-He liked reading the students' work.

He liked -- He liked budding creativity.

Really liked being around it.

And he liked the fact that the students looked up to him for guidance and that they asked real intelligent, well-informed questions about, "How did you do that?

How do I do it?"

-One of my problems going to Mount Holyoke and going to such a staid college was that they always complained that I wrote in Black English, and -- First they would complain that you're writing in Black English, and then I'd say, "Well, I speak Black English, and I speak, you know."

And they'd say, "Well, okay, if you're going to write in Black English, you gotta just write in Black English.

You can't mix it with regular old American language."

And, you know, so, those were the kind of battles I was fighting until Jimmy came along.

And Jimmy said, "Write whatever you want to write."

And, you know, not only, "Write what you want to write," but, "This is my experience, too.

You know?

This is real.

I can relate to this."

-Black people need witnesses in this hostile world which thinks, um, everything is white.

-Are you still... in despair about the world?

-I never have been in despair about the world.

I'm enraged by the world.

-Enraged.

Alright.

-But I don't think I'm in despair.

I can't afford despair.

I can't tell my nephew, my niece... You can't tell the -- You can't tell the children there's no hope.

-Most people would agree that Jimmy was a hero, in a sense, that Jimmy was an adventurer.

Jimmy didn't take the easy way.

There are people who have liked him to go on writing "Go Tell It on the Mountain" over and over again.

But Jimmy didn't like going back to what he had already done.

Now, it may be that in any given novel he wasn't as successful as he was in some other given novel, but that's the game.

That's the game of writing novels.

It's not an easy game.

And, uh, the things he attempted in the later works were much more difficult, I think.

-You know, James Baldwin gave Black people an example.

I know he inspired me to write.

When you see another Black person out there writing, when all you've been fed is Milton and Shelley and all these people who were dead 200 years ago, that gets your attention.

-God knows the handicaps and the hazards are very, very, very real and, you know, tremendous.

But if we can get beyond the place where we are now, something very important may happen in the world.

I believe that.

-He brought that cry into the cocktail parties, as well as the universities, as well as the streets.

And I think that all of us, you know, owe James Baldwin -- those of us who are interested in Black liberation, those of us who are interested in human progress, and those of us that are interested in writing -- owe him a great -- a great debt.

-On the 1st of April, Jimmy had an appointment at the Institut Cinc, which is a private hospital.

And they gave him an examination and found that it was cancer.

He said the doctors had told him it was very, very serious and he knew it was very, very serious.

But he had things to do.

He would say, "I'm skating on my reputation now.

I've got to do something else."

He wanted to finish a play.

He was rewriting a play, "The Welcome Table."

And he wanted to get that done.

He knew, himself, that it wasn't going to be as long as I thought it would be, because he gave up his novel.

He read the first six pages of his new novel to me, then he gave that up.

-The last letter I got from him, he wrote on July 4th.

And he said to me... "July 4th!

'87.

My Dear Cindy, a note.

Forcing myself to attempt to write by hand in an attempt to counter arthritis..." Of course, he doesn't mention the operation at all.

"I suppose, in fact, that much of what I'm doing these days is an attempt to keep the lines of communication open.

I seem to be, anyway, as the church members always put it, clothed and in my right mind, but everything seems very strange and tentative.

The way of time is different.

It goes fast, much more slowly.

It is gone, suddenly, the day, which had seemed so slow and heavy.

And then there is the night, where I've always been more at home.

I seem to curl up in the stillness at the center of the dark.

I listen.

And something is listening to me.

All journeys are extraordinary.

But one has got to make many, perhaps, in order to find this out.

What a marvelous phrase, to find out."

-Well, we never mentioned that he was going to die.

He was quiet.

Reading.

Eating.

A little, not much.

Sweet as always.

Very, very nice.

No complain.

No complain.

Nothing.

-The last place he came, when he was very sick, was here, and had salami and bread and butter, cheese.

And it was -- At that time he was very sick, but he'd gotten up.

He wanted to go out.

He said, "I want to go see Yvonne."

And I said, "Okay."

So we brought him here.

And they sat there, and I just left them alone.

He said one morning -- He said, um... "I see Simone's face on the wall."

"Do you ever see people's faces on the wall?"

He said, "I see her face on the wall."

And I called the doctor, and the doctor said, "I think he's going to go tonight."

And -- He couldn't swallow anymore.

So I was trying to find a bent straw, so he could pull it in.

He didn't have the strength to pull it in a straw.

-And that -- In the evening, I went out of his room, told David to come help me bring -- take Jimmy.

And we stayed there.

David felt it was the last hour.

Yes, it was amazing.

We were the three of us, sitting.

David was holding his hand, and I was sitting on a chair, in the beginning, and Bernard was putting water on his lips.

David talked to him.

We felt -- We felt -- He looked at us.

He looked at us.

He didn't talk.

He looked at us.

And it -- I have the feeling we accompanied him, you know, a part of his trip.

And Jimmy looked, little by little, looked elsewhere, and as I told you, we accompanied him.

Then, personally, I had the feeling, at one point, I came back, came back to life.

He was gone.

That was it.

Jimmy had gone.

♪♪ -[ Singing in native language ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Everybody who came into contact with Jimmy had his or her life changed, I think.

And that's the mark of a real teacher.

It's the mark of a real preacher.

And it's the mark of a prophet, and I think Jimmy was in many ways a prophet.

-He said, "I pray I've done my work so, that when I've gone from here and all the turmoil, through the wreckage and rumble, and through whatever...

When someone finds themself digging through the ruins..." He said, "I pray that somewhere in that wreckage they'll find me.

Somewhere in that wreckage.

That they can use something that I left behind.

And if I have done that, then I've accomplished something in life."

[ Exhales deeply ] -A day will come when you will trust you more than you do now... ...and you will trust me more than you do now.

And we can trust each other.

I do believe, I really do believe in the New Jerusalem.

I really do believe that we can all become better than we are.

I know we can.

But the price is enormous, and people are not yet willing to pay it.

-♪ Precious Lord ♪ ♪ Take my hand ♪ ♪ And lead ♪ ♪ Lead me on ♪ ♪♪ ♪♪