I first fell in love with the words of James Baldwin during my senior year at Vassar College.

While working toward a B.A. in French Literature (along with a D.E.F. degree from the Sorbonne / Institut des Sciences Politiques in Paris), I read everything Baldwin wrote from Go Tell It on the Mountain to The Fire Next Time. I then became a writer myself: first as an editor at Simon & Schuster; a reporter / editor for LIFE Magazine; and a foreign correspondent for TIME Magazine. After leaving Time Inc., I traveled the world as a freelance journalist, writing stories on everything from Vietnam to Hollywood. Journalism led to film, and an award-winning documentary film script (“The Fed”). Then – after two Hollywood screenplays plus a year producing TV commercials – I joined Maysles Films.

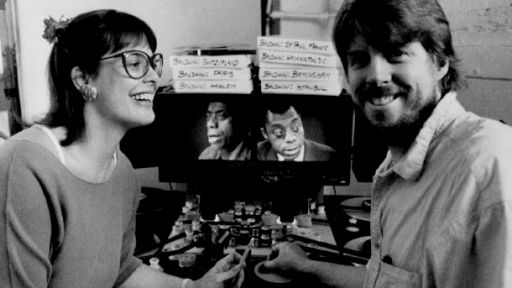

It was 1986 when Albert Maysles and I began collaborating on a film project with James Baldwin. Our goal was a cinéma-vérité film about the writing of Baldwin’s next book. Then, on December 1st, 1987, at age 63, James Baldwin died. A cinéma-vérité film was no longer possible – but the need for a film about Baldwin suddenly took on new importance. Susan Lacy, Executive Producer of the award-winning PBS series, American Masters, agreed – and with Al Maysles’ blessing, I became the film’s director.

The first event that I filmed was James Baldwin’s funeral.

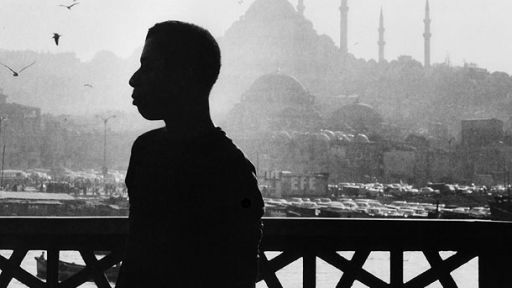

Funded with my own savings, it gave me credibility as a filmmaker – and allowed me to begin raising funds elsewhere. After forming a non-profit production entity (Nobody Knows Productions), I enlisted the help of historical filmmaker / archival master Bill Miles as my Co-Producer. Gradually, our team formed: Co-Producer / Co-Writer Douglas Dempsey; Associate Producers Joy Birdsong and Joe Wood. Then came twelve months of research and six weeks of production (with Cinematographer Don Lenzer and Sound Recordist Peter Miller): in Istanbul, the South of France, Harlem, Connecticut and North Carolina … all places where Baldwin chose to live and work. Then, finally (with Editors Steven Olswang and Sandra Guthrie), we spent eight intense months combining our original material with the wealth of archival footage, audio recordings and still photographs that we’d unearthed in nine different countries.

I’m extremely proud of all we accomplished. A film which tells Baldwin’s tale and spreads his message of brotherhood, in his own words, without narration. A film which, like Baldwin’s writings, has now been translated, screened and broadcast in countries all over the world.

The whole experience was a privilege. I’ve often said that during the making of Baldwin, I felt like a conduit … for something far greater than anything I could do or say on my own. Somewhere back in post-production, one of our editors said, “I’ve only been on this project two weeks, and already Baldwin has changed my life.” He certainly changed mine. After years as a so-called idealist, after years as a writer on the fringes of film, I met Jimmy – and everything meshed. Suddenly I had the courage to take the next step. We all did.

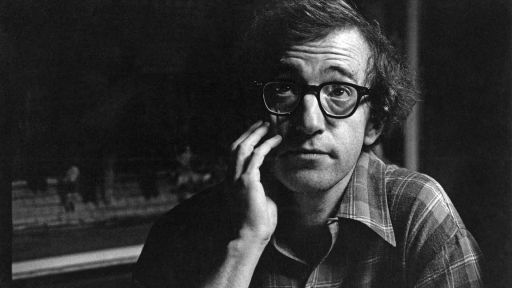

Jimmy does that to people. Here was someone lucid, honest, constant, saying the things we felt but never really said. Here was someone who lived what he believed, someone tough-minded enough to say not that the world would change, but that it could change … if we’d just make the effort. And he was real: excessive, exuberant, frustrated, torn– With the guts to insist that we really are brothers, that love is not an indulgence, it’s an imperative. As he says on camera, near the end of his life and near the end of this film:

“The day will come when you will trust you more than you do now, and you will trust me more than you do now. And we can trust each other. I do believe, I really do believe in the New Jerusalem, I really do believe that we can all become better than we are. I know we can. But the price is enormous – and people are not yet willing to pay it.”