Producer and director Jeremy Marre spoke to AMERICAN MASTERS about the making of the film and what he wanted it to reveal about this legendary artist.

Producer and director Jeremy Marre spoke to AMERICAN MASTERS about the making of the film and what he wanted it to reveal about this legendary artist.

Q: Why did you select James Brown as the subject for your film?

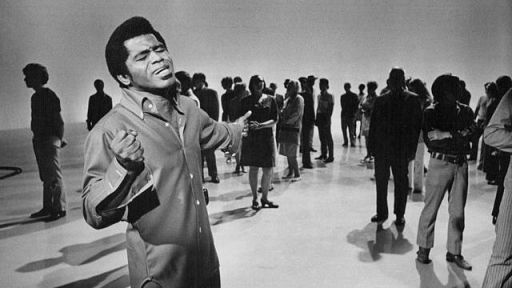

Jeremy Marre: I don’t know exactly when I first became interested in making a film about James Brown. I’d been aware of his music for years, but when I make a film about someone, it has to tell a story, it has to reveal the character and personal history of that man or woman, it has to uncover new aspects of his or her life, struggles, achievements, and creative powers, and James Brown seemed to fulfill all these criteria.

I had seen little that revealed the power and majesty of his musical vision and much that emphasized the weaknesses or misfortunes that filled headlines and occupied TV trivia programs. My aim was to present Brown’s life and music within the context of his times, propelled and to some extent explained through his own words and through the eyes and ears of those closest to him, personally and professionally.

Q: What aspect of James Brown’s life held the greatest interest for you?

JM: The political context of his work particularly interested me, and Brown is such a three-dimensional character: he leaps at you from vinyl or CD through the intensity and originality of his rhythms and through that striking contrast between his successes and suffering, his immense strengths and all too apparent weaknesses, the love and loathing he inspired, and his ability in the face of overwhelming odds to be and to remain James Brown.

Q: When do you think you became aware of James Brown and his musical impact?

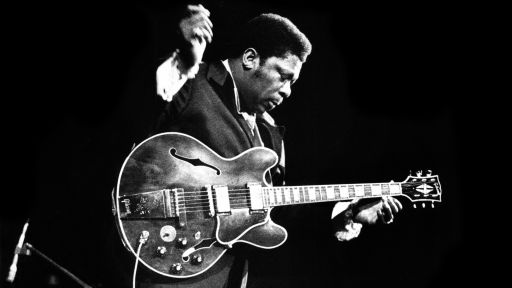

JM: I’ve no idea when I first became aware of James Brown. He’s one of those figures you somehow feel you’ve always been aware of. I’ve made so many films about music and musicians, a large number of them in America, that it’s been impossible to escape his influence, his musical shadow, by which most, if not all, contemporary musicians have been touched. When I made my first overseas music film, ROOTS ROCK REGGAE, Bob Marley and Bunny Wailer told of Brown’s influence. More recently, I made REBEL MUSIC for AMERICAN MASTERS, and again the debt to Brown (his earlier soul sounds) became apparent. More recently still, I was making a three-hour TV series called THE VOICE, which examined the power, influence, and evolution of the world’s “great” voices (from Caruso to Sinatra, from Pavarotti to Dylan, from Chuck D to Bono), and again Brown’s name at some time appeared on everybody’s lips: from the soul era or funk or his influence upon hip-hop and rappers. “Without Brown,” said Wyclef Jean, “there would be no rap as we know it,” and so the music of Brown seems to have accompanied me all through my travels and films of the recent years, in Africa (Nigeria to the Congo), in Asia (India to Japan), and across the Americas and Europe.

Q: Did you learn anything unexpected about the artist during the filming?

JM: I suppose the thing that surprised me most about James Brown, while I was making the film, was his political status in America during the ’60s. “Is This the Most Important Black Man in America?” asked a leading magazine in 1968, and the answer is probably yes. Brown symbolized black aspirations, announced black pride, and delivered a statement in words and music that inspired and uplifted his people — all people — at that time. “Don’t Be a Drop-Out” and “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud” were fiercely independent statements by a man who was nobody’s puppet.

When he flew to comfort James Meredith (the civil rights spokesman who had been shot in the back), or when he performed in Boston to keep his people from looting and burning, or played in Vietnam against the wishes of the white political establishment, or supported Martin Luther King, James Brown was a spokesman who inspired both admiration and fear in the hearts of different sections of American society. I also learned that Brown’s early life — with its joys, separations, incarceration, rejections, and overriding ambition — shaped the man and his music. When Mr. Brown, in the course of this film, describes the source of his famous scream, it’s a chilling reminder of the era he lived in and the personal scars that remain upon a man who appears to have the brazenness and ego of a king, but is in fact as vulnerable as that small child whose mother deserted him in a one-room shack in South Carolina.

Q: Are there any interesting anecdotes from the making of the film that you’d like to share?

JM: Perhaps the most vivid anecdote I can bring to mind is my first filming with James Brown. The crew and I were dressed in suits and ties (as instructed) ready to welcome Mr. Brown (as we were told to call him). When the door swung open, a tirade of abuse was heaped on us by the man himself: who did we think we were, how could we presume to tell his story, he was the only man in the world who knew who and what James Brown was, that he would tell us nothing, nothing … a baptism of fire indeed. Then Mr. Brown sat down and asked why we hadn’t been filming his offensive! He was ready to start now. He’d made his point. James Brown likes to be in charge.

There were other great moments. A two-minute drive in his car became a four-hour filming session as he spontaneously revisited the places of his past in Augusta, Georgia — where he was arrested as a child; the brothel he grew up in; the canal where he hid, submerged, from the police; the school that rejected him for wearing unsuitable clothes. Or when we all prayed quietly together over dinner, holding hands, or when we were allowed to film an intense band rehearsal (something Brown has always kept private in the past), and Brown grabbed the mike and gave the band a heart-wrenching rendition of “Georgia.” All as unforgettable as the Southern hospitality we enjoyed.

Q: How would you describe your approach to the film?

JM: My approach to the film was, as I said, to reveal the true man behind the music, and thereby reveal the heart of the music itself. To do so required four days of in-depth interviewing with James Brown, and unfettered access to reveal — at performances and rehearsals — the power and appeal of his music, as it evolved from gospel to raw soul, to political statement, to funk to prototypical rap. I wanted to get away from objective commentary styles. Because of the powerful nature of this music — and indeed this man — I wanted to put as much as possible in his own voice and words. And then counterpoint it with observations — often revealing and sometimes less than sympathetic personally — by the men and women who were most intimate with Brown during his extraordinary career. So I had the idea to use his autobiography as a commentary, explaining from within the source of his music, and the anxieties, deprivations, and achievements of his life. When they came from the man himself, they had a different perspective, a stronger emotion, than any third-person commentary could impart. I wanted to reveal the changes in the man and his music as his life progressed, and as he was confronted by the massive hurdles that were placed in his way, sometimes deliberately by others, sometimes by himself. I should add that Brown never interfered with the content, and neither he nor his entourage requested any changes to the cut they saw.

Q: What were some of the obstacles you encountered while making this film?

JM: There are always obstacles. Restrictions in time and budget mean you can’t film everything and everybody you want. Chasing voices, interviewees who could reveal, intimately, the real James Brown was never easy. Wonderful characters like Bobby Byrd, singers like Marva Whitney and Martha High, musicians like Fred Wesley and Little Richard, friends like Dan Aykroyd (remember THE BLUES BROTHERS?) and the Reverend Al Sharpton, who knew and loved Brown since he was a child. To find them, and a dozen others (from his first girlfriend to his traveling partner in Vietnam) confronted us with logistical problems and many an anxious wait, while the snow fell around us and flights were diverted. But find them we did.

I was even banned from entering the theater where we shot his live show, at House of Blues, because I’d forgotten my British passport. It was only when our long-suffering line producer discovered my picture (at a party) in BEAT magazine and thrust that under a guard’s nose that I was allowed to enter and direct a show that included an unforgettable 16-minute version of “Man’s World.” Incidentally, much more of that live show, and some phenomenal rehearsal sequences too, will be available as extras on the DVD of this film.

Q: Can you talk a bit about the other films you’ve made?

JM: I’ve made too many films to list, but they’ve often been music documentaries or musical biographies. I’ve mentioned REBEL MUSIC (the life of Bob Marley) and THE VOICE, but I’ve tended, in general, to make films where I felt there was something that needed saying and where I as a filmmaker could help make a statement on behalf of people who had no access to the media. My BEATS OF THE HEART series (about world music) shows how music can be the voice of a people (“the cry of the people,” Jimmy Cliff said): from the gypsy or Romany people who still travel across borders to black South Africans, then still suffering under apartheid, or the proud musicians of the Tex-Mex borderlands. I’ve made many films about people who are outsiders, even within their own countries, and that too, in its way, applied to James Brown. I’ve also made a number of programs in the series CLASSIC ALBUMS, looking at the detailed process of making and recording music. And I’ve shot real-life stories, from Madagascar to Mexico, from China to Thailand, that tell of people’s struggles to make their voices heard, and of the impact that just one voice can have upon the rest of the world. And that’s James Brown too.