“As I always said, if people wanted to know who James Brown is, all they have to do is listen to my music.”

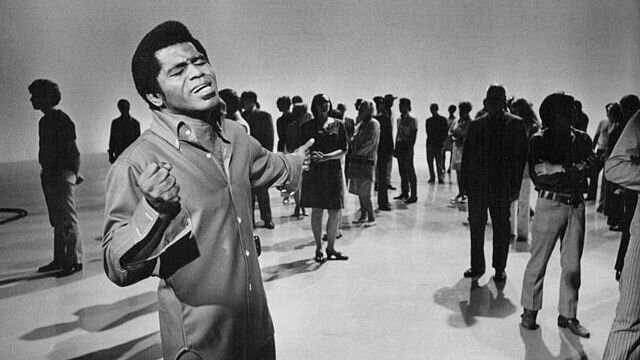

“The Hardest-Working Man in Show Business,” “Soul Brother Number One,” “the Godfather of Soul,” “the Minister of New New Super Heavy Funk” — in whatever guise, James Brown is unquestionably one of the most charismatic musical icons of the 20th century. An irrepressible performer, ruthless but highly proficient bandleader, awesome dancer, and, unquestionably, the man who flipped soul music on its head to create funk, Brown became a huge black cultural symbol in the 1960s and ’70s. He’s certainly altered the course of black popular music more than once, with his innovations flowing into the careers of Michael Jackson, Mick Jagger, Public Enemy, Prince and a multitude of others.

“The Hardest-Working Man in Show Business,” “Soul Brother Number One,” “the Godfather of Soul,” “the Minister of New New Super Heavy Funk” — in whatever guise, James Brown is unquestionably one of the most charismatic musical icons of the 20th century. An irrepressible performer, ruthless but highly proficient bandleader, awesome dancer, and, unquestionably, the man who flipped soul music on its head to create funk, Brown became a huge black cultural symbol in the 1960s and ’70s. He’s certainly altered the course of black popular music more than once, with his innovations flowing into the careers of Michael Jackson, Mick Jagger, Public Enemy, Prince and a multitude of others.

The music he cut in his prime, as well as his idiosyncratic screams and squeals, have formed the bedrock of hip-hop. He’s subsequently become the world’s most sampled artist. He’s also had to struggle with addiction and personal tragedy, especially in his later years. In 1988, he was imprisoned for two years, convicted of aggravated assault and failing to stop for a police car following a high-speed police chase from Georgia into South Carolina. His third wife, Adrienne, died unexpectedly after undergoing plastic surgery in 1996. But today, he still tours, and his performances belie his septuagenarian physique. James Brown is undoubtedly a complex, sometimes misunderstood, but always absorbing figure.

James Brown’s early career

He was born in a one-room shack in the woods of South Carolina in 1933. His parents split up when he was four years old and he moved in with his Aunt Honey, the madam of a brothel in Augusta, Georgia. Poverty dominated his youth; he danced for money, shined shoes, picked cotton, and was dismissed from school for “insufficient clothes.” He developed his unique, compelling voice by singing in church. But at the age of 15, after breaking into a car, he was sentenced to between eight to 16 years in jail. While incarcerated, he led a gospel choir, demonstrating his organizational prowess at an early age, and was befriended by a local musician, Bobby Byrd. Upon his release three years later, he was aided by the Byrd family and became part of Bobby’s vocal group.

Eventually gravitating toward R&B music, the group, which came to be known as the Famous Flames, performed across Georgia in the mid-’50s. They impressed Ralph Bass, a King Records talent scout, with their demo tape of “Please Please Please,” and the song was released in 1956, becoming their first hit single. In 1958, “Try Me” was also released and more hits followed. In the late 1950s and the 1960s, James Brown stubbornly mastered every dance craze like the “camel walk,” the “mashed potato,” and the “popcorn.” He invented some too, often declaring he was about to “do the James Brown.”

His concerts were passionately anticipated. “Pee Wee” Ellis, his saxophonist, once commented: “When you heard James Brown was coming to town, you stopped what you were doing and started saving your money.” Recorded in 1962, the album LIVE AT THE APOLLO is an awesome document of Brown’s dramatic shows and the raw, emotive power of his voice. The record sold millions of copies, establishing James Brown as one of the leading black performers of the period.

James Brown and The Flames

The Flames toured ceaselessly throughout the 1960s, often performing five or six nights each week, and Brown, who promoted and planned his tours, was a sharp businessman, hitting “money towns” at the weekends. A perfectionist, he famously fined his musicians for missing notes or playing the wrong ones. And when he yelled out the name of a musician, that person was expected to improvise perfectly on the spot. Another saxophonist, Maceo Parker, admitted, “You had to think quick to keep up.” In 1965, during THE T.A.M.I. SHOW in Santa Monica, James Brown performed before the Rolling Stones. Of their respective performances, music historian Nelson George, observed: “Mick Jagger jiggled across the stage doing his lame funky chicken after James Brown’s incredible camel-walking, proto-moon-walking, athletically daring performance.”

In 1965, the immaculate rhythmic tension of “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” ushered in a new style of music — funk. Throughout the 1960s and into the early 1970s, James Brown increasingly abandoned melody and harmony, focusing on rhythm in songs like “Cold Sweat,” “I Got the Feelin’,” and “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose.” Brown admitted, “I was hearing everything, even the guitars, like they were drums.” By the end of the 1960s, he was mercilessly reducing every instrument to a percussive role.

James Brown and the civil rights movement

James Brown’s involvement with the civil rights movement also began in the mid-’60s. He embraced it with the same energy and dynamism he devoted to his performances. In 1966, the song “Don’t Be a Drop-Out” urged black children not to neglect their education. In the same year, he flew down to Mississippi to visit the wounded civil rights activist James Meredith, shot during his “March Against Fear.” From 1965 onward, Brown often canceled his shows to perform benefit concerts for black political organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1968, he initiated “Operation Black Pride,” and, dressing as Santa Claus, presented 3,000 certificates for free Christmas dinners in the poor black neighborhoods of New York City. He also started buying radio stations.

By 1968, James Brown was very much more than an important musician; he was a major African-American icon. He often spoke publicly about the pointlessness of rioting and in February 1968, informed the black activist H. Rap Brown, “I’m not going to tell anybody to pick up a gun.” On April 5, 1968, African Americans rioted in 110 cities following civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination the day before. James Brown was due to perform in Boston, Massachusetts. Mayor Kevin White and Brown decided to proceed with the show and televise it. They realized people could not resist watching a James Brown concert, and the riots gripping other cities were averted in Boston.

In May 1968, President Lyndon Johnson invited James Brown to the White House. The following month, the government sponsored him to perform for the troops in Vietnam. In August, he recorded “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Brown later attested the song “cost me a lot of my crossover audience,” but it definitely caught the rising spirit of African-American nationalism and became the unifying anthem of the age. He graced the cover of LOOK MAGAZINE, which asked, “Is this the Most Important Black Man in America?”

James Brown’s legacy

Throughout the first half of the 1970s, James Brown continued to make the charts with songs like “Sex Machine,” “Get on the Good Foot,” and more political material like “Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing.” His popularity dipped momentarily when he supported Nixon’s reelection in 1972, but he bounced back, writing the soundtracks to BLACK CAESAR and SLAUGHTER’S BIG RIP OFF. In 1973, his first son, Teddy, died tragically in a car accident and the IRS stalked him for millions in back taxes, but the concerts and hits didn’t stop. He performed at the Ali-Foreman fight, “the Rumble in the Jungle,” in Zaire and was paid $160,000 to play at the President of Gabon’s inauguration in 1975. In 1976, 20 years after his first hit single, James Brown entered the charts with “Get Up Offa That Thing,” but his career was consumed by disco, a payola scandal, and financial and domestic difficulties.

In 1980, his appearance in the film THE BLUES BROTHERS was the start of his comeback. Having a hit single with “Living in America,” from ROCKY IV, helped too. In 1986, he was one of the first inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Emerging hip-hoppers, like Afrika Bambaataa and Public Enemy’s Chuck D, either recorded with him or praised him as an important influence. Despite this, Brown continued to struggle, very publicly, with personal demons, imprisonment, and addictions well into the 1990s.

James Brown wrestled free of these afflictions. In 2001 he married singer Tomi Rae, who’s borne him a son, James Brown II. He also raised $30 million on Wall Street against future royalties. He performed regularly, quickly selling out such prestigious venues as London’s Albert Hall. Even the state of South Carolina has officially forgiven him for his late-’80s transgressions. James Brown is undoubtedly a soul survivor:

“Where I grew up there was no way out, no avenue of escape, so you had to make a way. Mine was to create JAMES BROWN.”

by James Maycock