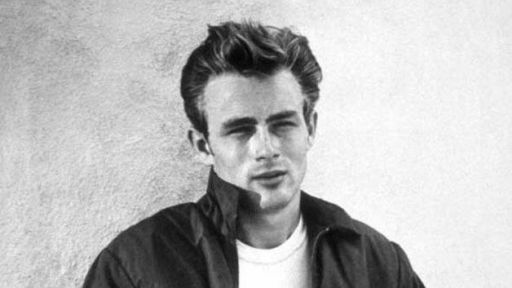

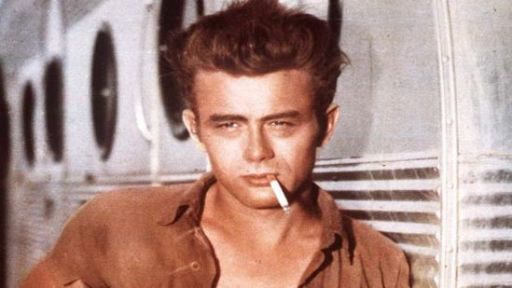

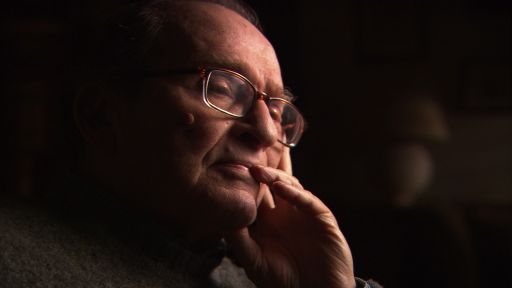

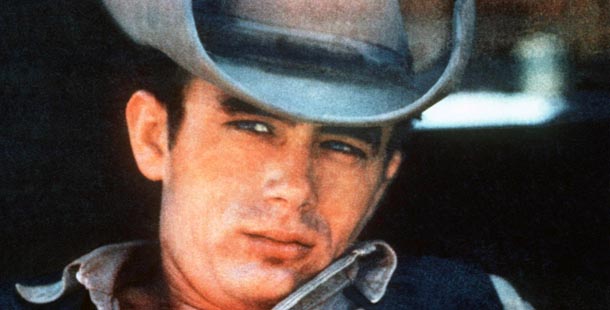

Excerpted from photographer Dennis Stock’s book, “James Dean: 50 years Ago.”

1955

“…When I look back at Los Angeles in the early fifties, and specifically Sunset Boulevard, it reminds me of the board game in which you try to move clockwise and upward, past designated obstacles, into “Stardom and Wealth.” Rolling the dice at the start, as a visitor on Mexican downtown Alvaro Street, the player inches past the pastel bungalows of Old Hollywood. With many other aspirants, we come to a holding pattern at the crossroads of Crescent Heights and Sunset. This intersection marks the beginning of the infamous Sunset Strip. If the dice were good, the roller continued and was hurled into the status filled setting of Beverly Hills. A jump or two more and the ultimate was at hand: a sunset-bathed beach house. This road was literally and figuratively bumpy, curved and highly deceptive. Till this day, few participants reach the Pacific enclave of the stars. Those who do are usually badly scarred and bruised.

“…When I look back at Los Angeles in the early fifties, and specifically Sunset Boulevard, it reminds me of the board game in which you try to move clockwise and upward, past designated obstacles, into “Stardom and Wealth.” Rolling the dice at the start, as a visitor on Mexican downtown Alvaro Street, the player inches past the pastel bungalows of Old Hollywood. With many other aspirants, we come to a holding pattern at the crossroads of Crescent Heights and Sunset. This intersection marks the beginning of the infamous Sunset Strip. If the dice were good, the roller continued and was hurled into the status filled setting of Beverly Hills. A jump or two more and the ultimate was at hand: a sunset-bathed beach house. This road was literally and figuratively bumpy, curved and highly deceptive. Till this day, few participants reach the Pacific enclave of the stars. Those who do are usually badly scarred and bruised.

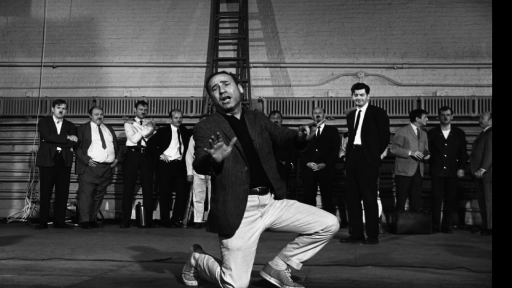

The Sunset Strip in the fifties (I doubt it has changed much) was the battlefield for those who needed to conquer Hollywood. In this two-mile area of nightclubs, restaurants, strip joints, and agents’ offices the struggle for recognition was fought. Starlets, directors, producers and actors elbowed one another for the space of two brief lines in the trade gossip columns. The establishments on the strip thrived on the anxiety of the fame-seekers, catering to the illusion of success; the prices were high, the facades ornate. Waiting at the foot of the strip for their turn were contestants who lived in the romantic hotels and cottages of the bygone twenties.

Those who arrived from the disciplines of the Broadway environment tried to make as gentle a transition into Hollywood as possible. They lived in the symbolic settings of the Chaplin and Keaton era, the Chateau Marmont and the Garden of Allah. The aging bungalows and suites insulated the ambivalent seekers from the East. The coffee-shops, diners, and drugstores were commandeered by the less affluent and served as social centers for the New York crowd. It was in this surreal, intense atmosphere that I met James Dean for the first time…

There was no question that our meeting was investigatory in nature. Sparingly, Jimmy volunteered information about his background, and I elaborated on my qualifications and credentials. His awareness of my friendship with Humphrey Bogart and my membership in the elite photo agency Magnum helped to further the idea of a collaboration. My intent was solely to lead the conversation back to Jimmy’s past so that I could start to formulate an outline of situations that we could visit and document with the camera. The story, as I explained it, was to reveal the environments that affected and shaped the unique character of James Byron Dean. We felt a trip to his hometown, Fairmount, Indiana, and to New York, the place of his professional beginnings, would best reveal those influences. We agreed to a trip to both of those locales in the not too distant future. As was customary in my business, I would solicit an assignment guarantee to cover expenses. The obvious magazine to approach was Life. If I was assigned to the Life editors, we could set up a schedule for visiting Indiana and New York. We further agreed that I would have the first exclusive rights to the picture story on Jimmy.

It took only a week for Life to approve the assignment. I notified Jimmy, and we tentatively set our departure for Indiana and New York for two weeks hence. Meanwhile, I made a point of socializing a great deal with Jimmy, for the more I knew about his moods, the easier it would be to anticipate gestures and situations. By now there was an ever-increasing interest in the new star as the press became more and more aware of East of Eden. The upshot of Jimmy’s increasing popularity was reflected in the new stipulations he tried to enforce on the Life coverage. At one point he insisted on a cover guarantee and the hiring of a friend of his to write the text. It was an unusual and highly egocentric gesture. I said I’d pass the request on to the editors. It was a foolhardy demand, which I never conveyed to the magazine, gambling on our growing friendship to keep the assignment afloat. I told Jimmy the editor’s answer was no. For days he acted like a spoiled kid, and then finally came around, making it possible for us to leave for Fairmount the first week in February, 1955.

For Jimmy it was going home. But it was also the realization the meteoric rise to fame that had already begun to cut him off forever from his small-town Midwestern origins, and that he could never really go home again. Still, in those bitter-cold late winter days, as Jimmy and I roamed the town and farm and fields of Fairmount, visiting family and friends, I came to know, or at least to glimpse the real James Dean.”