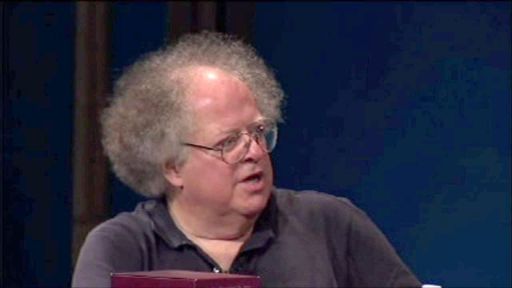

Susan Froemke answered questions via email about the making of the documentary James Levine: America’s Maestro. This interview was originally published on Inside Thirteen.

Can you discuss the role Maestro Levine played in transforming the Metropolitan Opera’s Orchestra into what it is today?

Susan Froemke: I learned during the filming that when Levine became the music director of the Metropolitan opera in 1974 at age 31, he felt that the Met was a great orchestra but one that needed improvement in certain areas. He also believed that opera was in a state of quiet crisis and told the New York Times at the time, “I often think, my God, I’m going to be in the generation that sees this whole thing die.” For him, what was at stake was the quality and emotional content of the Met’s performances.

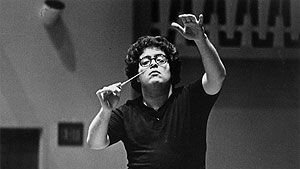

Levine’s dream was to bring the Met orchestra up to the level of the Cleveland Orchestra at its peak. “I wanted to hear the Met orchestra play Mozart operas with the sophistication and communication of detail like George Szell’s Cleveland Orchestra.” In the 1960’s, Levine had studied for six years with Szell, first as an apprentice and later as an assistant conductor. Szell, a Hungarian born autocrat, had built the Cleveland Orchestra into one of the country’s finest symphonic ensembles. It bothered Levine that many people thought an opera could be performed better in concert with a symphony orchestra on the stage than with an opera orchestra in the pit. He felt that this shouldn’t be the case. He said, “The orchestra that plays in the pit should produce a panorama of expression, of details, that’s astonishing from beginning to end.”

So Levine accepted the job of music director but only after he was able to obtain control over casting, musical staff, directors and designers. This was the first time in the Met’s history any conductor had held this position.

His vision was to bring the Met into the contemporary era by broadening and expanding the orchestra’s repertoire, increasing the capacity of the orchestra, chorus and ensemble, and rotating the repertoire with new productions.

To do this, he made a commitment to stay in New York and developed a kind of collaborative stability with the orchestra that existed in opera before the jet age when maestro’s built orchestras.

David Langlitz, principal trombone, recalled in one interview, “In rehearsals, I’d see him work slowly over a period of weeks, sometimes even months, looking for a particular sound, looking for a particular interpretation, and just patiently going with it, going through it, working with a player. That’s the way to build an orchestra: we feel as if what we’re doing is valued.” Numerous players echoed this sentiment.

He really invigorated the Met orchestra, making it into a world-class ensemble.

During one of our last shoot days, Levine told me, “After all the work I’ve done over the 40 years with the orchestra, I find they are more dramatic, more lyric, more vocal, more consistent, more committed, more able to deal with the pressure than any other orchestra. And there’s stability to the way we work that produces a different kind of result than you can get in any relationship that is more ad hoc. You can’t conduct that. They have to know how to do it.”

Was there anything you were surprised to learn about Levine and/or his career during the making of this program?

I knew that Maestro Levine was a genius musically. I saw it every time I filmed him rehearsing with his orchestra, working with a renowned singer or coaching a young artist. What I wasn’t aware of was his business acumen—something often lacking in artists. During his tenure at the Met, he has always had a vision of where he wanted to take the company. When he sensed during the late 70’s that the Board leadership was weak, he was savvy enough to ask for more artistic control so there would be no creative backsliding. When top management positions became available, he lobbied for people whom he could partner with successfully to achieve his goals. He always kept an eye on the box office even while introducing new, unfamiliar productions from modern composers in the 70’s and 80’s.

How does Levine differ from other prominent conductors, and what makes his approach to music and conducting unique?

I’m not really an authority on this subject but I can offer some anecdotal observations. Many of the Met musicians that I spoke to agreed that Levine–to some degree–ushered in the “love conductor” era. As demanding as his musical ethos is, it’s still a far cry from that of the old-fashioned tyrant conductors like his mentor George Szell or Herbert von Karajan.

In 1987, I filmed Karajan during the Salzburg Summer Festival rehearsing the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (one of the world’s best) for a rare Wagner concert. Karajan was exacting in his instructions, often insulting the players as though they were schoolboys. He drilled them over and over on certain passages, barking at them until he finally got the sound he wanted. Levine couldn’t be more different. He absolutely does not believe in being confrontational because it doesn’t build relationships. If some player or singer is having a bad day, he will never criticize them then. He is aware of human limitations.

Michael Ouzounia, the Met’s principal viola player and longtime friend says, “He gives musicians a certain latitude for being temperamental. I think he feels that his function is to get the best performances out of the forces, and not to be imposing because he doesn’t really believe you can impose. He grew up in a milieu where fear was a component of orchestra playing, but that doesn’t suit his personality. He developed a way to get great results without being autocratic.”

Ray Gniewek, a former Met concertmaster agrees, “His approach is one of understanding. It gives players, especially those who had played under stricter conductors, confidence that he was going to help you through a difficult spot, not challenge you.”

I think Levine’s understanding of human psychology and the role that confidence plays in delivering a strong performance is one of his strongest assets.

What do you think played more of a role in informing Levine’s career, instinct and innate talent, or his training (as a pianist and conductor) and musical upbringing?

I believe James Levine was born to do what he was meant to do.

There is a wonderful story I heard about his childhood. When he was two years old, his father and mother would always sing him to sleep. The next morning, he would climb out of his crib and pick out the tune–sung to him the night before–on the piano! He was a child prodigy whose parents made all the right decisions on how to encourage his talent and educate him.

While filming, Jimmy told me: “I was born with a degree of talent that is impossible for me to understand frankly. It’s sort of like being born with a voice. I was very fortunate that almost every aspect of music, whether it was artistic style, content, or technical fascinated me and I had very good teachers. Right from the beginning, I was able to learn in a sort of continuous flow. I didn’t really have any problem.”

When he was a kid, he used to listen to the Saturday Met opera broadcasts. As a ten year-old, he traveled to New York every other week during the winter season to take lessons from Rosina Lhevinne on the piano. He said that he probably went to two opera performances every couple of weeks at the Met. Later, while he was in Cleveland, he studied quite a bit with Pierre Boulez. He remembers: “I brought music to him, asked him questions, and had a kind of Socratic dialogue with him. When people ask me today, where do you get an education like that? I guess it’s always true that you have to produce it for yourself. You have to go after it. I think I worked for everything.”

Levine feels that it’s important to continue to learn and he does, from his orchestra players and contemporaries. He expects it. But he also believes: “I’d been given a lot of talent and I thought it was part of the deal that if you’re one of those people who gets a lot of talent, you have to be responsible to it. So where the passion for the art form is concerned, I find it necessary to use every fiber to keep making the work better.”

This is not the first film you have made centered on the Metropolitan Opera and more broadly, classical music in general. What attracted you to making films about this genre?

First of all, I thank my lucky stars that I’ve been able to produce so many classical music films. Peter Gelb, the Met’s general manager, and I started making films together 25 years ago. At the time, I was making documentaries with Albert and David Maysles and Peter would introduce us to great musicians who were often experiencing critical life changes. This was perfect for our cinema verite style of filmmaking, which Peter became a practitioner of as well. We made films on Vladimir Horowitz, Mstislav Rostropovich, Jessye Norman, Osawa and many others. Each film had a very different narrative but each also contained extraordinary musical performances whether in rehearsal or concert.

In the course of the filming, we would have to discover the narrative so, on one level, I never considered that I was making a film in a certain genre. I was more concerned with storytelling, character development, and capturing the drama as it unfolded before the camera–just as I would be with any subject. But deep down, I always knew that I could count on a few astonishing performances from these great artists that would complement the narrative action in each film. I was never disappointed. These films tell great human stories but they also give the audience the best seat in the house during an outstanding musical performance. That’s the great appeal to me of this genre.

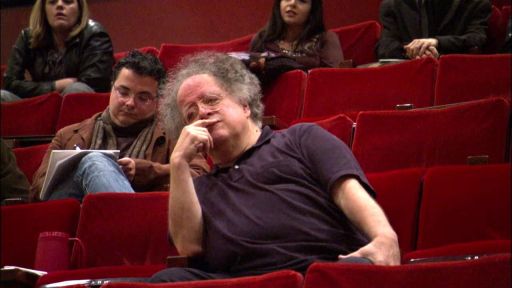

At one point in the film, in an interview at the New York Times, Levine refers to himself as a “teacher conductor.” We also get to watch him working with the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. How much do you think Levine’s love of teaching has shaped his role in the opera community, his repertoire, and how he views himself?

Maestro Levine is a self-professed “teacher conductor” and I think, within the world of classical music, no one disagrees. It’s his modus operandi. It is how he has built the Met orchestra into one of the world’s best. When you watch him rehearse, he talks throughout telling the players in detail what he wants and why. He makes them repeat a phrase until he feels they have it in their minds and can do it without him. Through this approach, the orchestra becomes more agile in their ability to play in a large variety of styles which, in turn, has allowed Levine to expand their repertoire.

It’s uncanny how so many singers — from Placido Domingo to very young artists — have told me that they learned more from Levine in one hour of coaching than in three years spent at a vocal school. Another consistent remark I heard was how he has an almost psychic ability to know exactly what a singer needs at any given moment. With his ability to clearly communicate the necessary instruction and through positive reinforcement, he leads the singer to a new understanding of text or technique.

I believe Maestro Levine is driven to teach because he feels it the most important work that he does. Through numerous rehearsals, he knows he can achieve a performance that is the intent of the composer. And that is always his greatest goal.

What was the hardest part of making this documentary?

For me, the hardest part was not being able to include more scenes of Levine working with the singers in the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. There were 12 singers in the class we filmed and we had marvelous footage of Levine working with them, especially when they first began the program and were quite “green” despite their talent. His intuitive, passionate coaching was just fascinating to watch. The depth of his understanding of the text of some of the world’s most famous arias, which the students were attempting to sing, was revelatory. You can see I’m a fan! His work with them probably changed many of their career trajectories. It communicated so strongly what his genius is that I really regret not being able to incorporate more of that footage into the film.