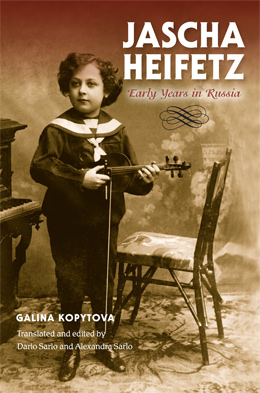

Jascha Heifetz: Early Years in Russia, by Galina Kopytova. Translated and edited by Dario Sarlo and Alexandra Sarlo. Indiana University Press, 2014. 504 pages.

Sixteen-year-old Jascha Heifetz’s American debut, Carnegie Hall, October 27, 1917

Book excerpt courtesy of Indiana University Press. All rights reserved.

On the day of Jascha’s American concert debut, people filed into the building until they were turned away: “The audience that witnessed the debut at Carnegie Hall Saturday afternoon was not only very large,” wrote Pitts Sanborn in the Commercial Advertiser and Globe, “but notable for the number of professional violinists it included—apparently every disengaged man and woman in town that ever drew a bow for money.”

According to a report in the Violinist journal, the many prominent violinists present at the debut included: Fritz Kreisler, Mischa Elman, Maud Powell, Franz Kneisel, Sam Gardner, David Hochstein, David Manner, Nathan Franko, Albert Greenfeld, Leopold Lichtenberg, Geraldine Morgan, Louis Siegel, Sam Franko, Gustave Saenger, Emily Gresser, Edith Rubel, Edwin Grasse, Helen Ware, Maurice Kaufman, and Victor Kuzdo.

With such an intense atmosphere developing in the auditorium, Jascha’s experienced pianist, André Benoist, began to feel a little nervous: “no matter how inured one may be to such occasions, it is almost impossible to remain entirely indifferent to them. I must confess that, in spite of many experiences of the same kind, I felt a bit aflutter myself.” It seems, however, that Jascha did not share the feeling of nervousness. As Benoist recalled: “When I reached the old Green Room at the hall, I found Mama and Papa Heifetz sitting about, as calm and unconcerned as if they were about to witness a Christmas party. As for Jascha, he ran up to me in high glee and said, ‘Look! Look! Fine long pants! Fine cutaway coat! Fine new necktie! I look fine, no?”

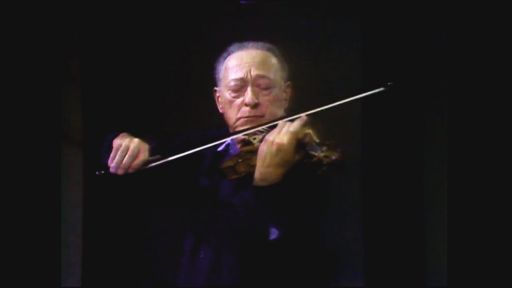

When the time came, Jascha walked out onto the stage to face an electrified public, and a deafening wave of applause broke out all around. As a reviewer in The World noted: “Some measure of the advance estimate in which this Russian youth is held was shown when he first appeared before his anxious throng. No sooner was he sighted than a wave of applause sounded through the big auditorium: a greeting so spontaneous, so sincere as to cause the seasoned concertgoers to exclaim involuntarily.” Jascha started with the Vitali Chaconne, with organ accompaniment provided by Frank L. Sealy, and as one reviewer noted, “long before the completion of the Vitali Chaconne it was apparent that a master violinist superlatively endowed had come to disclose the measure of his worth.” After each subsequent piece, the delight and excitement in the audience continued to grow. Jascha then played the Wieniawski Concerto no. 2, Schubert’s Ave Maria, Mozart’s Minuet, Chopin’s Nocturne in D, the Beethoven Chorus of Dervishes and March Orientale, Tchaikovsky’s Melodie, and the Paganini Caprice no. 24. Another reviewer noted that “this boy was establishing new violin marks; that in every department of his art he was the superior of any fiddler this country has known in at least fifteen years.” It was at this debut that a very well-known anecdote between a famous violinist and pianist came to life: “It’s hot here, isn’t it?” said Mischa Elman to Leopold Godowsky, who was sitting in the same box. “No, Mischa. Not for pianists,” Godowsky quickly responded.

The calm and unconcerned behavior of Jascha’s parents before the debut attested to the unwavering faith they had in their young son’s incredible talent. After all, they had seen and heard him conquer every stage on which he had set foot, throughout the Russian Empire and Europe. Just as elsewhere, the crowd in Carnegie Hall cheered and applauded and rushed the stage at the end of the recital. In this sense, Carnegie Hall was just one more venue to add to the burgeoning list of accomplishments in Jascha’s career. His overwhelming success on October 27, 1917, however, provided him a special place in the hearts and minds of the American public, and ultimately resulted in the family’s decision to remain in the United States. Political circumstances far out of their control had led the Heifetzes to make the epic journey to New York, leaving behind the country that had raised Jascha and contributed to the formation of his musical character. With years of preparation behind him, Jascha was ready for this next stage of his life.

Certainly, this move was not easy for Jascha. He left behind the country that had been his home, and he left behind many friends: people from the conservatory, including Glazunov, who had facilitated the family’s stay in St. Petersburg-Petrograd; Viktor Valter, his constant supporter; beloved Professor Auer, the man responsible for Jascha’s artistic training; and Kiselgof, who had worked tirelessly to broaden Jascha’s education. The Heifetzes also left behind the Sharfsteins, who would eventually join the Heifetzes in the United States, but not for another five years. Others in the wider Heifetz family ended up staying in Russia, including Natan and Fanny and their daughter Lyusya, Ruvin’s other siblings, and Jascha’s grandparents. Some of these people Jascha would never see again.

Despite the sacrifices, if Jascha and his parents needed proof that they had made the right choice, back in Petrograd, just days after the debut in New York, the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution (on November 7 in New York City, but October 25 in Petrograd). A lengthy and brutal civil war ensued. No one in Russia knew how and when the situation would end. The Heifetzes, at least, were safe in the New World.

——

The one-hour documentary American Masters — Jascha Heifetz: God’s Fiddler premieres nationwide Thursday, April 16 at 8 p.m. and Friday, April 17 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings).