In the late 1950’s, Jasper Johns emerged as force in the American art scene. His richly worked paintings of maps, flags, and targets led the artistic community away from Abstract Expressionism toward a new emphasis on the concrete. Johns laid the groundwork for both Pop Art and Minimalism. Today, as his prints and paintings set record prices at auction, the meanings of his paintings, his imagery, and his changing style continue to be subjects of controversy.

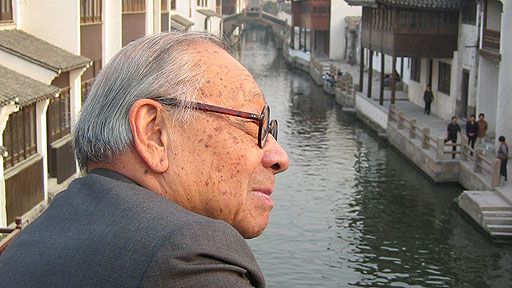

Born in Augusta, Georgia, and raised in Allendale, South Carolina, Jasper Johns grew up wanting to be an artist. “In the place where I was a child, there were no artists and there was no art, so I really didn’t know what that meant,” recounts Johns. “I think I thought it meant that I would be in a situation different from the one that I was in.” He studied briefly at the University of South Carolina before moving to New York in the early fifties.

In New York, Johns met a number of other artists including the composer John Cage, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, and the painter Robert Rauschenberg. While working together creating window displays for Tiffany’s, Johns and Raushenberg explored the New York art scene. After a visit to Philadelphia to see Marcel Duchamp’s painting, The Large Glass (1915-23), Johns became very interested in his work. Duchamp had revolutionized the art world with his “readymades” — a series of found objects presented as finished works of art. This irreverence for the fixed attitudes toward what could be considered art was a substantial influence on Johns. Some time later, with Merce Cunningham, he created a performance based on the piece, entitled “Walkaround Time.”

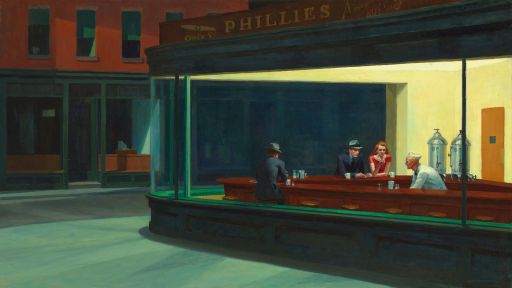

The modern art community was searching for new ideas to succeed the pure emotionality of the Abstract Expressionists. Johns’ paintings of targets, maps, invited both the wrath and praise of critics. Johns’ early work combined a serious concern for the craft of painting with an everyday, almost absurd, subject matter. The meaning of the painting could be found in the painting process itself. It was a new experience for gallery goers to find paintings solely of such things as flags and numbers. The simplicity and familiarity of the subject matter piqued viewer interest in both Johns’ motivation and his process. Johns explains, “There may or may not be an idea, and the meaning may just be that the painting exists.” One of the great influences on Johns was the writings of Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. In Wittgenstein’s work Johns recognized both a concern for logic, and a desire to investigate the times when logic breaks down. It was through painting that Johns found his own process for trying to understand logic.

In 1958, gallery owner Leo Castelli visited Rauschenberg’s studio and saw Johns’ work for the first time. Castelli was so impressed with the 28-year-old painter’s ability and inventiveness that he offered him a show on the spot. At that first exhibition, the Museum of Modern Art purchased three pieces, making it clear that at Johns was to become a major force in the art world. Thirty years later, his paintings sold for more than any living artist in history.

Johns’ concern for process led him to printmaking. Often he would make counterpart prints to his paintings. He explains, “My experience of life is that it’s very fragmented; certain kinds of things happen, and in another place, a different kind of thing occurs. I would like my work to have some vivid indication of those differences.” For Johns, printmaking was a medium that encouraged experimentation through the ease with which it allowed for repeat endeavors. His innovations in screen printing, lithography, and etching have revolutionized the field.

In the 60s, while continuing his work with flags, numbers, targets, and maps, Johns began to introduce some of his early sculptural ideas into painting. While some of his early sculpture had used everyday objects such as paint brushes, beer cans, and light bulbs, these later works would incorporate them in collage. Collaboration was an important part in advancing Johns’ own art, and he worked regularly with a number of artists including Robert Morris, Andy Warhol, and Bruce Naumann. In 1967, he met the poet Frank O’Hara and illustrated his book, In Memory of My Feelings.

In the seventies Johns met the writer Samuel Beckett and created a set of prints to accompany his text, Fizzles. These prints responded to the overwhelming and dense language of Beckett with a series of obscured and overlapping words. This work represented the beginnings of the more monotone work that Johns would do through out the seventies. By the 80s, Johns’ work had changed again. Having once claimed to be unconcerned with emotions, Johns’ later work shows a strong interest in painting autobiographically. For many, this more sentimental work seemed a betrayal of his earlier direction.

Over the past fifty years Johns has created a body of rich and complex work. His rigorous attention to the themes of popular imagery and abstraction has set the standards for American art. Constantly challenging the technical possibilities of printmaking, painting and sculpture, Johns laid the groundwork for a wide range of experimental artists. Today, he remains at the forefront of American art, with work represented in nearly every major museum collection.