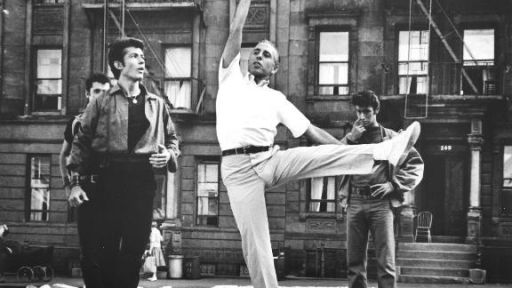

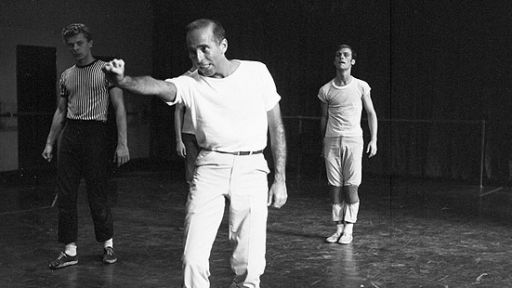

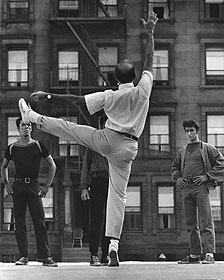

Jerome Robbins rehearsing West Side Story film.

Copyright: The Robbins Rights Trust

Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz was born in New York on October 11, 1918 and raised in Weehawken, New Jersey.

Deprived of a college education by the Depression, he began his career as a dancer in the experimental troupe of Gluck Sandor. George Balanchine cast him in the chorus of a pair of Broadway shows, and soon after, he got into Ballet Theatre (later American Ballet Theatre). There he came under the tutelage of choreographers Mikhail Fokine, Anthony Tudor, and Agnes de Mille, and attracted attention in a number of roles, most notably as Fokine’s Petrouchka.

But Ballet Theatre’s Russian-influenced repertory stifled him.

“I thought, ‘Why can’t we dance about American subjects?’” he said later. “Why can’t we talk about the way we dance today, and how we are?” Recruiting an unknown young American composer named Leonard Bernstein to write a score, he concocted Fancy Free, a jazz-inflected ballet about three sailors on shore leave that received 22 curtain calls at its premiere on April 22, 1944. And eight months later Robbins and his collaborators turned the ballet into On the Town, a Broadway hit that extended the boundaries of what the musical could achieve.

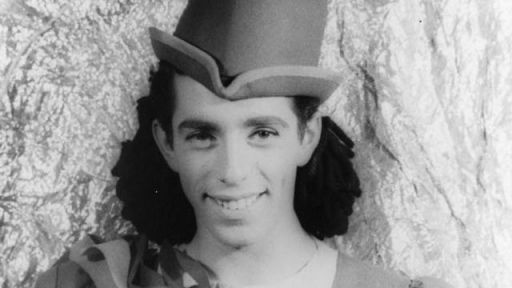

Soon Robbins was working with every major figure in musical theatre and – with such shows as Billion Dollar Baby and High Button Shoes – displaying an inexhaustible gift for combining character, comedy, and storytelling in dance. In 1948, he reconnected with Balanchine, who had just founded the New York City Ballet with Lincoln Kirstein. There he won audiences with his performances in Balanchine’s Prodigal Son, Tyl Ulenspiegel and other ballets, and with the innovative, character-based choreography of such works as The Guests, Age of Anxiety, and The Cage.

He continued to make award-winning dances for Broadway as well, and with The King & I earned his first ticket to Hollywood.

But in the midst of this success, Robbins found himself swept into the whirlwind of the McCarthy era and, as a former Communist, pressured by the FBI to name the names of party associates at hearings held by The House Committee on Un-American Activities. (HUAC). For three years he resisted. But threatened by exposure of his homosexuality, he at length agreed to testify before HUAC and named eight people. One of them, the late actress Madeleine Lee Gilford, says that as a result she and her husband, actor Jack Gilford, “did not have any TV or film work and we managed mostly on unemployment insurance.” Robbins himself never spoke of his testimony publicly; in his journal he wrote, “Maybe I will never find a satisfying release from the guilt of it all.”

If he did find release, it was in his work. In the aftermath of HUAC he created some of his signature ballets – Afternoon of a Faun and The Concert, both made for the ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq – and extended his theatrical reach to directing as well as choreographing with Pajama Game, Peter Pan, and Bells Are Ringing. In 1957 he enlisted his old collaborator Leonard Bernstein, plus the playwright Arthur Laurents and novice lyricist Stephen Sondheim, to re-imagine Romeo and Juliet for the gang-ridden streets of New York City. The result was West Side Story, a show conceived, choreographed and directed by Robbins. Said former theatre critic Frank Rich, “It was as if, for the first time, something modern and new was crashing into the commercial Broadway world.” Robbins also co-directed the film version of West Side Story with Robert Wise; and although he was let go before completion for allowing his perfectionism to wreak havoc with the budget, he still won two of the movie’s ten Academy Awards, for his co-direction and his choreography.

The success of West Side Story was followed by a string of Broadway hits.

He directed and choreographed Gypsy (1959) starring Ethel Merman, and supervised the production of both A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) with Zero Mostel and Funny Girl (1964) with Barbra Streisand. In 1964 he directed and choreographed Fiddler on the Roof, which became the longest running musical of its time. It was also to be Robbins’ last — but he continued to push the limits of his art, exploring experimental theatre with the American Theatre Lab in the late 1960’s, and returning triumphantly and joyously to ballet with works like Les Noces, Dances at a Gathering, Goldberg Variations, Glass Pieces, and many others.

Although his work was garlanded with 48 prestigious awards, Robbins rarely felt satisfaction with his success. Notes Mikhail Baryshnikov, “For Jerry, every achievement was torturous.” But despite a bicycle accident in the 1990s and open-heart surgery in 1995, Robbins kept making dance. At the age of 79, six weeks after overseeing a revival of Les Noces for New York City Ballet, he suffered a massive stroke and died July 29, 1998.

Robbins never married or had children. At his death, the bulk of his considerable estate passed to the Jerome Robbins Foundation, which has helped numerous artists, arts organizations, and AIDS charities; with the aid of a multimillion dollar gift, it has also enabled the New York Public Library to develop the world’s largest dance archive. But Robbins’ most important legacy was the humanity of his art. “Give me something to dance about and I’ll dance it,” he once told Irving Berlin. As this film shows, in the theatre and in dance, he did that over and over again.