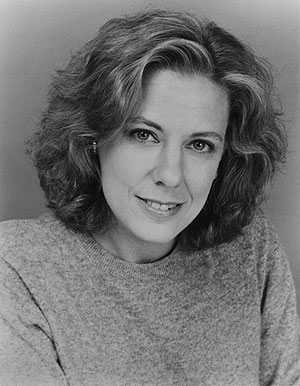

Judy Kinberg

With unlimited access to Jerome Robbins’ personal archive and performance library, Emmy-Award-winning producer/director Judy Kinberg captures a multi-faceted portrait of the complex mid-century master.

Robbins’ life and works touch upon the larger issues of 20th century American culture, from the evolution of musical theater and the development of American ballet to the aspirations and struggles of first-generation Americans and the effects of McCarthyism. Kinberg was a member of the original production team of the groundbreaking DANCE IN AMERICA series, winner of over 80 major national and international awards, including 20 Emmy Awards and two Peabody’s. She has developed an important body of work on dance, both performance programs and documentaries, including virtually every major American choreographer and dance company of her time, such as George Balanchine, Martha Graham, Jerome Robbins Paul Taylor, Frederick Ashton, Antony Tudor, American Ballet Theatre, New York City Ballet, and many others. The producer/director discusses her latest film, AMERICAN MASTERS Jerome Robbins: Something to Dance About, which premieres Wednesday, February 18, 2009 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings).

Q: You’ve worked with Jerome Robbins on past projects. Tell us about that experience.

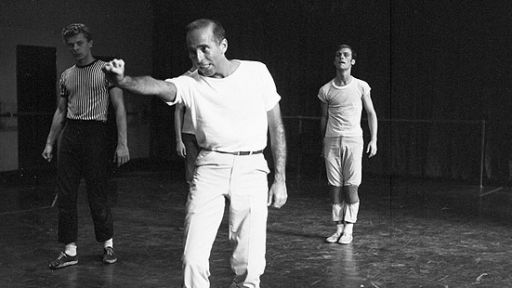

A: Robbins was a handful and a half from a producing point of view. We made three DANCE IN AMERICA programs with him, including the only complete recording to date of the much-loved Fancy Free and the beautiful Other Dances, with Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov. He was demanding, unsympathetic to our problems, funny, scathingly honest, told great stories, and had the best eye of anyone with whom I’ve worked. And there was some pretty stiff competition there. The entire time we were making the first program with him, it was often so painful that I promised myself I would never work with him again. And then I did.

Q: What makes him an American master?

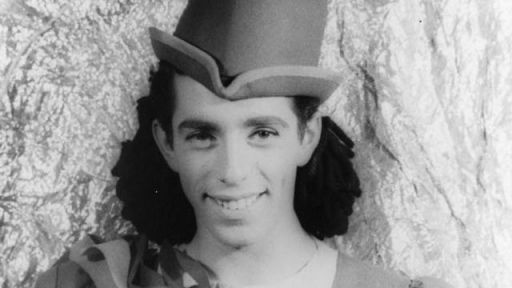

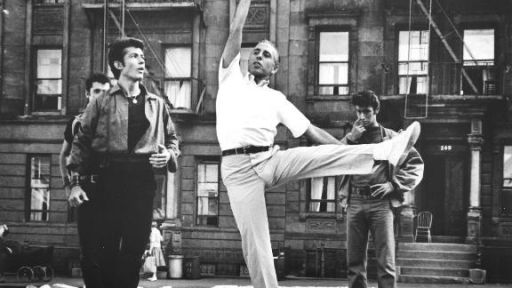

A: Robbins brought a uniquely American sensibility to his work, beginning with his landmark ballet, Fancy Free, which reflected his desire to “dance about how we are today,” rather than only perform the old Russian works that were the staples of ballet. He was a primary architect of four of the most enduring works of the American musical theater, including one, West Side Story, which was responsible for expanding and elevating the form, plus there is no more important American-born ballet choreographer. If that’s not an ‘American master,’ what is?

Q: How do you approach Robbins’ role during the McCarthy era when he testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC)?

A: Very, very carefully and as fair-mindedly as possible. We give the facts, both from Robbins’ point of view through his journal entries and also through several acquaintances, since he never discussed it publicly, and from the point of view of Madeline Lee Gilford, who he named.

Q: What would you say is the most compelling aspect of Robbins’ story?

A: I find the fact that Robbins was so full of contradictions fascinating. He was a wildly successful man who was riddled by insecurity, a man of enormous generosity who was capable of extreme selfishness, often inarticulate in person, but a poetic writer, a homosexual who very much wanted a family when those things were mutually exclusive, a natural storyteller who aspired to master the art of the abstract ballet, a man who rejected Judaism in his youth, only to produce Fiddler on the Roof. People can say completely opposing things about Robbins and both be right. It happened numerous times in our interviews, sometimes with a single person.

Q: What did you learn in making this film that surprised you the most?

A: I was very fortunate in that I was permitted to read Robbins’ diaries, and they were a revelation, not so much in what he said, but in how he said it. He was often described as “inarticulate,” and in person, he sometimes was, but I was greatly impressed by how he expressed himself in words, often poetically, and we’ve used many quotes in the program. We had an enormous advantage in that our writer, Amanda Vaill, had written Somewhere, a marvelous biography of Robbins, on which she worked for eight years, so she was thoroughly familiar with all his writings, whereas I was only able to read about twelve years’ worth.

Q: With so much great material to choose from, how did you decide what to include?

A: In some ways, there was too much material, such as all the hours of fascinating interviews we amassed, and in other ways, there wasn’t enough. There are just a few fragments of Robbins dancing, for example, and virtually all of them are in the show. There are no recordings of his original Broadway shows. Even the archive tape of his compilation show, Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, was not made with the original cast, and Robbins was so disturbed by the quality of the recording that he insisted a notice be put on the tape indicating that it did not represent his work.

In the case of the ballets, there are many which were not professionally recorded, and only archive tapes exist, which show just the architecture of the ballet from far away, but no detail, so they don’t generally represent a ballet in a way that would be useful in a film biography. So what we chose to include was, in some measure, limited by what recordings exist in which the viewer can actually see the dancing well.

What, finally, we decided to include were the dances we felt were most important and were best recorded and those which enabled us to illustrate the points we wished to make about Robbins and the interconnections with his work. Nothing is there simply to represent itself; each selection is tied to an idea or an event, our aim being to illuminate the artist through the work.

Q: How much influence does Robbins’ art have on dance theater today?

A: I think most Broadway choreographers would tell you they owe a debt to Robbins. He was instrumental in elevating the musical to an American art form. There’s a reason that his greatest shows are still revived – Fiddler and Peter Pan just a few years ago, Gypsy right now, and next year, West Side Story.

Q: From where does your love of dance come?

A: Mark Morris once told me that he believed “dance is for anyone, but not for everyone,” and I think he’s right. I discovered ballet at a relatively late age, by a stroke of good fortune. I was a dramatic literature major in college and had studied music, but had no exposure to ballet, when I was invited by a young man whose parents had a subscription to American Ballet Theatre, but couldn’t use the tickets, to join him for a performance. I had no idea what to expect, but it took place in a theater, so I figured I’d try it. As luck would have it, I saw a performance of La Sylphide with Carla Fracci and Erik Bruhn, and by the time the curtain came down, I was hooked. I’ve completely forgotten who my date was, but can remember the image of Fracci and Bruhn as if it were yesterday.