By Mary Wharton, Photos by James Fideler

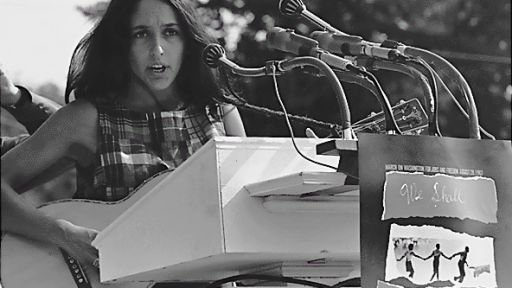

Growing up in the 1970’s, I was mostly aware of Joan Baez from her hits of that decade, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “Diamonds and Rust.” I don’t think I had any idea about her connection to Bob Dylan (I didn’t know that “Diamonds and Rust” was about him) and I was pretty much unaware of Joan’s earlier incarnation as the Queen of Folk. I do remember knowing that she was “political” and that as a kid growing up in the South during the Vietnam War, I had respect for a woman who was not afraid to speak her mind. I also remember being entranced by her exotic beauty and ethereal voice. But I can’t say that I really followed Joan’s career or knew any more than just the headlines of the Joan Baez story before I got involved with this project.

Embarking on the task of telling Joan Baez’s incredibly rich life story was daunting enough – I had much to learn about this multifaceted woman. To be a part of the widely respected American Masters series was both an honor and a source of added pressure. American Masters is the home of great films by great directors, and it was important that this piece be worthy of both the series and of it’s subject. Easier said than done.

Joan Baez’s 2008 tour had been set up with stops in places that played a part in Joan’s story. Her manager, Mark Spector, served as a producer on the film and it was his idea to film Joan in those places and reconnect her with people from her past. His thinking was that these scenes would resonate in the film in a more powerful way than a typical interview. Some of these situations worked out better than others, but Mark’s instincts were correct. The shoots that were successful turned out to be some of the most emotional moments in the film.

Everyone who has seen the film remarks about the strength of the scene where Baez sits down with her ex-husband David Harris. I think that’s because it’s rare to see two people be honest with each other about what drew them together and what drove them apart. If the two people were simply interviewed and that footage was intercut in a “he said, she said” exchange, you would miss the power of the look in their eyes as they confront their bygone relationship face to face.

What’s not spelled out in the film is that the scene was shot at Struggle Mountain, the northern California commune where Joan and David lived together while they were married. It’s hard to say if the conversation would have been different if we had shot it somewhere else, but I believe that the immediacy of the location allowed a certain openness in the conversation that would have felt stilted and false in a television studio or some other hired location.

Another location that had a definite power over the film was Sarajevo. Although we were only in Sarajevo for a few days as we followed the Joan Baez tour from Bosnia to Slovakia, the experience of being in Sarajevo and the people I met there will stay with me forever.

Planning a shoot in Sarajevo was not without risk. When you’re making a documentary, you always run the risk that you’ll start shooting and not capture anything compelling, or that something compelling is happening, but you aren’t able to capture it because of timing, technical difficulties, or any number of different reasons. But when you spend a lot of time and money just to get to a place and then you only have a few days there to get what you need for the film, the pressure increases.

We knew that the story of Joan’s trip to Sarajevo during the siege in 1993 was compelling – we had the archival footage of that trip – anyone could see that this was a great piece of Joan Baez’s history. Mark managed to track down Vedran Smailovic, who Joan had met when she was there, and arranged for him to meet us in Sarajevo for the shoot.

Vedran Smailovic was once a cellist for the Sarajevo Opera who had witnessed a horrific massacre during the war. In response, he did the only thing he could think to do – he played his cello. Every day for 22 days, in honor of the 22 people who were killed in the massacre, Vedran went into the street in his tuxedo with his cello. In an extraordinary act of bravery, he risked being shot by snipers or killed in an explosion so that he could play the same piece of music every day – Albinoni’s Adagio. (Read about Vedran’s experience in this New York Times article from 1992).

When Joan went to Sarajevo in 1993, she was taken to meet this man – at the site of the massacre, where he was performing. You can see in the archival footage that Joan is wearing a bulletproof vest. In some shots, you can hear sniper fire and explosions. We did not add any sound effects to this part of the film. Anything you hear is actual gunfire and explosions from the real footage of Sarajevo at that time. It was a difficult and dangerous time to go to Sarajevo. It is estimated that an average of 15 people were killed and 44 wounded every day during the siege. The airport was closed; roads into the city were barricaded. But that didn’t stop Joan Baez. She was told that she could help the people there, and so she dropped everything and she went.

During the siege, normal people were trapped in Sarajevo. Serbian forces took up positions in the hills surrounding the city and kept up a constant assault with rocket-launched aircraft bombs, heavy machine guns and random sniper fire. Shipments of medical supplies, food, and heating oil were cut off. People were starving, freezing in winter, and cut off from outside news. Many lived in underground shelters to stay out of the line of fire. This went on for almost 4 years. Joan Baez’s visit was the first tangible sign to the people of Sarajevo that the outside world was even paying attention to their plight.

After the siege had ended, Vedran got out of town as soon as he could and had not returned – except for one quick return trip to rescue his cello. But he agreed to come back “For Joan,” and asked us to send him money to cover his travel expenses. We wired him the money, with some trepidation. Not knowing if his Bosnian accent would prevent American viewers from understanding what he said, or if the reunion with Joan would be as powerful as the original meeting in the archival footage had been, or even if he’d really show up. But we took a leap of faith and hoped we had made the right decision.

We decided to travel with only the key members of the crew, to save money, and hire local crews wherever we went (Again, not without an element of risk – would the crew be any good? Would they speak English?). We narrowed down the traveling crew to just myself, the director of photography, James Fideler, and Anthony Decurtis, the respected music writer who had signed on to the film to help guide the conversations and conduct interviews. Mark would be traveling with Joan on her tour bus and we’d join the tour in Sarajevo.

After some 20 hours of travel, with stops in London and Budapest, James, Anthony and I arrived in Sarajevo. (By the way, if you’re ever stuck in the Budapest airport, the local brew that they serve in the bar is actually quite tasty and helps to wile away the hours…) It was late at night when we finally arrived at our destination – but one of our two cameras did not make the journey.

The airport baggage office told us the equipment had missed the flight from New York to London, and had been re-routed to Atlanta for another flight that would supposedly connect with the next flight into Sarajevo – the next day. We were scheduled to shoot the next day and I knew that even in a best-case scenario – the 2nd camera would not arrive in time. I called our fabulous associate producer, Joyeux Noel, back in New York to ask her to find us another camera. Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to track down a high-definition digital video camera in Sarajevo on a moments notice, but I was worried that it would be impossible. I didn’t sleep much that night.

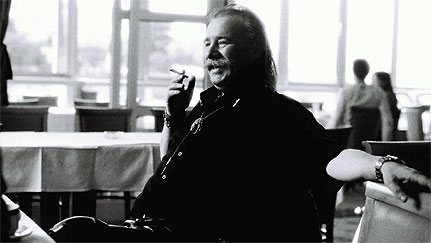

Vedran met us in the morning for breakfast at our hotel. He arrived like an angel of darkness, dressed head to toe in black leather, with silver skull necklaces around his neck, smoking like a house on fire.

After breakfast, Vedran took us to the shoot location – the street where he and Joan had first met. But now, instead of a war-torn bombing site – it was a busy shopping street, with bustling cafes and shops, like one would see in any modern European city. Worried that the actual spot of the bombing would be too noisy and hectic, I made arrangements with a nearby café to shoot there if it didn’t work out with the street scene.

Then Vedran insisted that he take us to a nearby café / bar that was decorated like a little curio box. It was gorgeous – every nook and cranny crammed with antiques and interesting objects. We met an old friend of Vedran’s there, who was so enthusiastic when he made a toast to Vedran that his wine glass shattered and the entire contents emptied onto my head and shoulders. I just sat there for one of those moments that feel like an eternity, until I saw a look of horror on Vedran’s face as he asked me, “Are you bleeding?” But it was just red wine, dripping down my face as I sat there in a state of shock.

So then it was back to the hotel, to change out of my wine-soaked clothes, and check in with Joyeux back at the office to find out what progress she had made with the camera. Our camera was still lost in transit, but we were told that it was scheduled to go on a flight to Vienna and would be routed to Sarajevo. I wondered if it would even make it there before we had to leave town. In the meanwhile, Joyeux had made arrangements for the local crew to bring another camera that was similar to what we were using, but not the right model. It would have to do.

When we all converged again on the street scene, it was even busier and noisier than it had been in the morning. In order for me to stay out of the sightline of the two cameras, I had to stand so far back from Joan and Vedran that I could barely hear what was said. Since their on-camera reunion only took about 5 minutes, I asked them to go over the story of their meeting again at the café, as a safety, because I wasn’t really sure that they had covered everything that I would need to tell the story.

When it was all said and done, I really didn’t know if this footage was going to work. I knew that the two cameras would never match exactly and I was concerned about how bad the audio would be with all the background noise. But I knew we had to try to make it work.

When I came back to start editing the film, I requested news footage from the siege of Sarajevo to help illustrate the story. I was surprised to find home video footage of the actual massacre that Vedran had described to me. I recognized the street because the buildings all looked the same except that in the footage, the windows were broken. But the street itself looked completely different from the place that I had been. Everywhere were dead and wounded victims of the bombing, and the street was literally a river of blood. It was the most horrific scene I have ever seen in my life. We used only the most tolerable moments in the film, and still it is harrowing.

As many times as I’ve seen it, the Sarajevo section of our film affects me every time. Just as the power of Joan’s voice, when she sings “Amazing Grace,” cuts through the other noise in that footage, the things that can sometimes get in the way of appreciating archival footage – bad video quality, background noise that sometimes overpowers what you really want to hear – are not a barrier here. Somehow the emotion of the scene overpowers the technical problems and it is incredibly moving. To me, this is one of the most important moments in the film.

When we first began this project, it was really important to me to show that Joan Baez has stayed true to her non-violent beliefs to this very day. When all the rest of the flower children cut their hair and became yuppies, Joan continued to fight for what she believed in, regardless of if was trendy or not and without regard to her reputation or even her own safety. Her trip to Sarajevo is by no means the only example of her ongoing commitment to human rights, but it certainly is a good illustration of the lengths that she has gone to further the cause of non-violence.

I entered into this project with respect for Joan as an artist and an activist. I ended it with a new hero. I can only hope that when I get to be her age that I look half as beautiful as she still does, and that I can maintain a creative career for as long as she has and still remain true to the reason that we both chose our respective careers in the first place – so that we could communicate with people. It feels pretentious to include myself in the same sentence as Joan Baez; I certainly don’t see myself as an artist on her level. But we are both storytellers, and the fact that I was given the honor of telling her story lets me put myself, if not on the same stage as her, as least in the building. I was there. This is what I saw. I hope that other people who watch the film will come away with as much love and respect for Joan Baez as I gained in the making of it.