Hippies, sex, art and politics. The Joffrey Ballet’s Astarte was the first multimedia production of it’s kind: it was a fusion of audience participation and rock ‘n’ roll music. After all it was the 1960s, but the performance went on to define the ballet company.

The ‘Astarte’ Interview

BY SHERI CANDLER

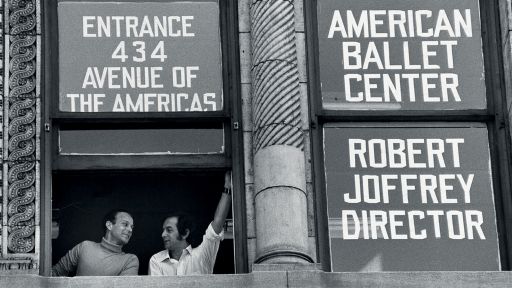

Having secured regular income and a new home at New York’s City Center complex, the company was up and running again after the near disastrous break with the Harkness Foundation. The years 1966-69 were a fruitful time of creation of work within the company and Robert Joffrey began to do something he had long strived for, reviving works by the masters from ballet history, particularly from the Diaghilev era.

Boris’s Cakewalk, Jooss’ The Green Table, Arpino’s Olympics, Trinity and The Clowns, Massine’s Le Tricorne were all notable works created or revived and performed at this time, but few had the same impact as Robert Joffrey’s Astarte.

Astarte is the Greek name of a goddess known throughout the Eastern Mediterranean from the Bronze Age to Classical times. She is associated with sexuality, fertility and war. Former Joffrey dancer Trinette Singleton remembers the day the rehearsal sheet went up announcing that a new ballet was being created by Mr. Joffrey:

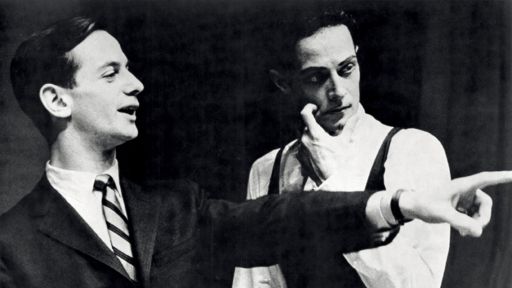

“When Astarte first started into rehearsals, nothing was said. The rehearsal sheet went up and it just simply said new ballet, my name, Dermot Burke’s name, and Robert Joffrey’s. We went in and we were nervous and excited to be working with Mr. Joffrey. We had no idea what to expect. There was no music and we simply started working on movement. Nothing was said; we were in the dark. That was the beginning. We were clueless.”

Dermot Burke injured his knee soon after rehearsals started and he was replaced by Max Zomosa.

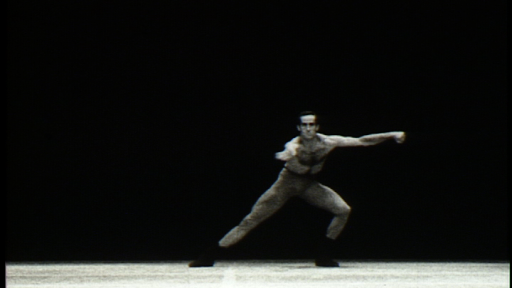

“Max had already been working with the company. He had done Death in The Green Table, so Mr. Joffrey knew his acting abilities were pretty stellar. For the longest time we were just in a studio working with Mr. Joffrey without being given the overview. He was just working on movement. The next thing that was added was music. He was using Iron Butterfly’s ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’ and having us move to certain rhythms in that.”

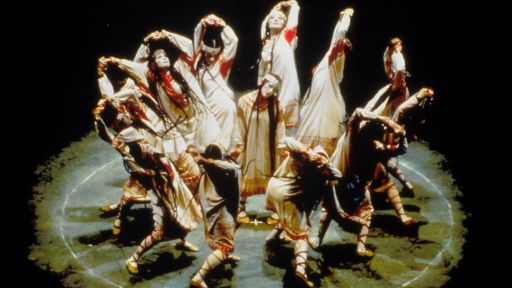

“We would do residencies at the Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington in the summers and that’s where a lot of times new works were created and so that was where we really got into working on this piece. One day, he brought in a musician, Hub Miller, that he knew from Seattle. He probably had been meeting and talking to Hub weeks and weeks before Max and I ever knew it, about writing a commissioned score for this particular piece. Hub wanted Mr. Joffrey to listen to a couple of rock bands that were sort of making a scene in Seattle at that time. So we go to this night club place and there’s a band playing, it’s the Chrome Circus, and suddenly they’re going to be doing the commissioned score for it, and Hub’s going to head it up. So, okay, there’s going to be a rock band in the pit. That was part two of the equation I guess you could say.”

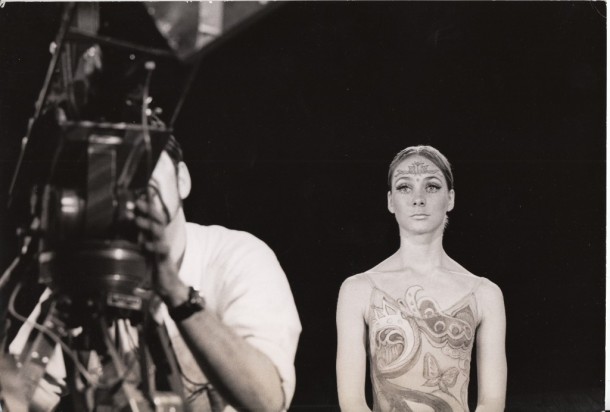

“We did some touring through Idaho and Iowa after that and the company manager came to me and said you’re leaving on the red eye out of here tonight, you and Max and Mr. Joffrey are going back to New York. Next thing I know, they’re trucking us off to the airport and put us on a plane. That’s when he sort of revealed the whole scope to us. And it was like ‘what do you mean we’re going into a film studio tomorrow morning?’ we were just shocked. We had no idea. We got off the plane and went to a film studio with Gardner Compton and Emile Ardolino and started filming.”

“I had some costume fittings. It was a unitard, and they kept painting all over it and drawing things on it. At the film studio, they had a makeup person. His name was Hugh Sherrer and he designed this very elaborate lotus tattoo and the big eyes and all of that. They put it on me every day and kept saying, ‘You have to learn to do this yourself’ and I’m like,’oh, okay.’”

“We started filming and that’s when they explained there were going to be cameras in this balcony and in this balcony, in this wing and in this wing. That’s when he said the background screen was going to be moving and the band was going to be in the pit and that was when Max and I sort of got the whole picture. It was all very secret and he didn’t want anyone to know that it was going to be a psychedelic rock ballet. We weren’t to tell anyone. I think he didn’t want people coming in with preconceived notions and rumors of what it could be, expectations of maybe what it was or wasn’t. I don’t think he wanted to give the critics an idea of what was going on. It was shock value. I think he wanted to surprise everyone.”

“When Max and I finally got this whole picture in scope, I was terrified. I was like ‘oh, my God, this is big.’ I was nervous. I mean what if I fail this man? What if I get onstage and just blow it, you know. It was nerve racking. Max wasn’t as nervous. Max was kind of bigger than life and he loved being the center of attention and drama.”