by Ken Bowser

John Ford and John Wayne — a friendship and professional collaboration that spanned 50 years, changed each others’ lives, changed the movies, and in the process, changed the way America saw itself. It was a relationship that reflected all the elements and all the paradoxes of 20th century America — generosity of spirit, abuse of power, a sense of loyalty, and a restless nationalism that didn’t quite know what to do with itself.

Ford had been a successful director for over a decade when he met Marion Morrison, at the time a young USC student working a summer job on the Fox lot as an assistant property man. He saw something in Morrison and gave the “kid” a few walk-ons in his films. Within two years Morrison had changed his name to John Wayne and Ford, very pleased with the young man’s work, recommended him to Raoul Walsh, another director on the lot.

Walsh was about to start one of the biggest films Fox had produced to date, THE BIG TRAIL, and the director gave Wayne the lead. The film ultimately flopped and Wayne’s career was quickly relegated to grade C westerns on poverty row. This was a situation many felt Ford could have stepped in to remedy, but over the next decade all the struggling young actor heard was that “Pappy was keeping an eye out for a script that would best suit the Duke,” his affectionate nickname for Wayne.

As Wayne’s career stalled Ford’s roared ahead; he was now one of the biggest directors in Hollywood. But the two men stayed friends — as long as it was clear who was boss.

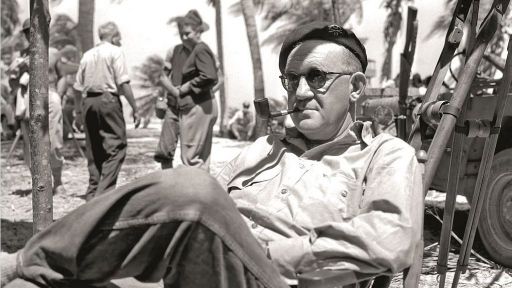

During these years, Ford (contrary to popular myth, which portrays him as a simple-minded, flag-waving conservative,) gained a reputation inside Hollywood political circles as a staunch Roosevelt Democrat. Wayne on the other hand had virtually no political opinions — his focus was on his career and family. The bond between the two men was largely the result of long cruises to Mexico and the Pacific Island chains on Ford’s yacht “Araner.” These jaunts, where Ford was accompanied by Wayne, Henry Fonda, Ward Bond, and others looked like nothing more than drunken pleasure trips, and for Wayne and the others that’s what they were. Unbeknownst to his passengers however, director Ford was spying. Since the mid-thirties Ford had been covertly photographing shorelines and shipping lanes for the American military in preparation for a war many in the War Department felt was inevitable.

It was after one of these voyages in 1938 that Ford teasingly asked Wayne to read the script of his next picture. Could Duke give him “some advice on what young actor might play the role of the Ringo Kid?”

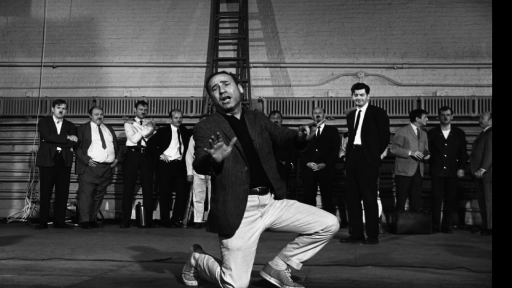

The script was STAGECOACH and Ford, after finally giving the part to the hungry actor, proceeded to taunt and belittle him throughout weeks of filming. Whether it was Ford’s infamously sadistic personality or a clever ploy to have the other actors support Wayne, the end result brought forth the persona that would come to be known as The Duke. The picture would make John Wayne a star overnight and bring the Western back to the forefront of American cinema.

Wayne would never forget it — not that there was any danger of Ford letting him.

When the war started almost two years later, Ford was already in uniform and had finished five pictures in the year and a half since STAGECOACH. Amongst them were YOUNG MR. LINCOLN, THE GRAPES OF WRATH, THE LONG VOYAGE HOME, and HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY. But for Ford these were just movies. The war would be the greatest adventure of his life — a call to arms by the country he loved that had given him everything. It also set up a conflict between Wayne and Ford that would ultimately push Wayne into politics in a major way.

John Wayne was thirty-one-years old, married, and supporting three children when the war began. His newfound stardom was a realization of a dream he was not in a hurry to relinquish to a uniform. Throughout the war, Ford urged the young actor “to get in it,” and each time Wayne would beg off until he finished “just one more picture.” Ford was disappointed to say the least, and he let Wayne know it. Wayne was growing richer as other men died. As the war continued, Ford’s strong disappointment fueled a growing conflict between the men and fostered a sense of guilt within Wayne. Wayne’s decision to stay out of the service would haunt him for the rest of his life.

In the years following the war, Ford’s films grew increasingly nostalgic as his disillusionment with post-war America grew. Injustice, racism, and greed seemed to be replacing the values he felt he and others had fought for. On the other hand, as Ford grew more introspective, Wayne saw the world open up in front of him with each new movie triumph. As their perspectives changed so did their relationship.

Between the end of the war in 1945 and Ford’s death in 1972, the two men made twelve films together. Those films helped define how we saw ourselves, or put another way, how John Ford wished us to be as Americans. From, THEY WERE EXPENDABLE, through the cavalry series — FORT APACHE, SHE WORE A YELLOW RIBBON, and RIO GRANDE — Ford made U.S. history both poetic and heroic. He also made John Wayne the personification of that history as well as the American male. Wayne the actor and star brought a reluctant power to those roles. That reluctant power was Ford’s principal and cherished idea of America’s greatness.

Being a symbol of America was a responsibility that ate away at Wayne. It was that sense of responsibility combined with his continuing guilt over not serving during the war that drove Wayne deeply into politics.

As the Cold War heated up and the Iron Curtain fell, Wayne began to merge his personal commitment to defending America with his screen persona. And from behind the camera, Ford’s vision of his country and his part in how it saw itself was shifting. With THE SEARCHERS, THE HORSE SOLDIERS, and THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, Ford would use the iconic image he’d helped Wayne create to cast light into the shadows of the country he loved. While Ford’s perspective may have grown darker, his love of America, its people and its landscape, never dimmed.

The growing difference of political opinion between the two men can be seen in two events. In late 1948, John Wayne became president of The Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Including the actors Ward Bond and Adolphe Menjou, producers like Metro’s James McGuiness, and director Sam Wood, the organization saw its principle goal as hunting down subversive elements within the American film industry.

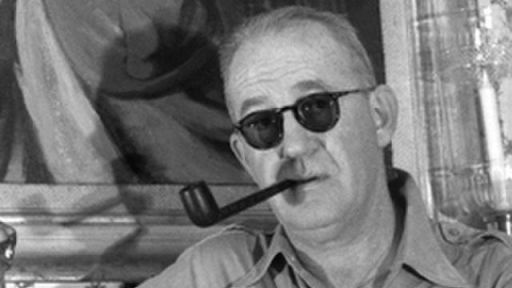

While Wayne was lending his star power to the anti-Communist forces, Ford was standing up at a historic Directors Guild meeting to stop the red hunters, led by C.B. DeMille, from firing the president of the Guild, Joe Mankiewicz, who they had come to view as dangerous. Ford famously rose after several hours of debate amongst the various factions and introduced himself humbly and ironically, “My name is John Ford and I make Westerns.” By the time he finished saying what he thought of DeMille for his sneak attack on Mankiewicz the tide had turned and DeMille and his followers had to do the resigning.

For the two friends politics became a topic that was left out of their conversations.

By the time the fifties ended John Wayne was the biggest star in the Western world. For Ford, who was pushing into his sixties, it was another story. His pictures were not the successes they once were and he found himself increasingly reliant on Wayne to get films done.

The politics, their careers, and the changing dynamics of their relationship would become clear on THE ALAMO.

THE ALAMO was John Wayne’s “vision of America’s greatness” — a simpler, more heroic America. He had been trying to get it made with himself as the director for years. Now at the height of his fame he was able to finally secure financing as long as he also starred. Under great pressure to prove himself he began production. He was barely a third of the way through when Ford showed up in Texas to “lend a hand.” Wayne was beside himself, he couldn’t just turn his mentor away. Finally Duke’s cameraman suggested they give Ford a second unit to shoot pick-up shots far away from the first unit. So Wayne, out of his own pocket, financed Ford to shoot a second unit. Very little was used in the finished film, but the rumors that Ford had to “save” Wayne were humiliating for the star.

By now it must have been clear to Ford that the son, so to speak, had surpassed the father. While THE ALAMO was hardly a huge success, it was now Wayne who wielded the power in the industry.

In later years as Ford struggled to get pictures made Wayne was always there for him, even on LIBERTY VALANCE, when the Duke had serious reservations about his part. If Pappy wanted him, that was it, the Duke showed up.

Kenneth Bowser is the writer/producer/director of NBC’s two-hour network special, LIVE FROM NEW YORK: THE FIRST FIVE YEARS OF SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, created for the 30th anniversary of SNL. His last film, EASY RIDERS/RAGING BULLS (a Trio/BBC co-production), was an official selection at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival.

Bowser also produced and directed the Emmy Award-winning documentaries “Preston Sturges: The Rise and Fall of an American Dreamer” and FRANK CAPRA’S AMERICAN DREAM (Columbia/TriStar Pictures). He has produced, directed, and written for ABC News Productions and is the writer/director/producer of the feature film IN A SHALLOW GRAVE (American Playhouse Theatrical Films.) In addition, Bowser was the director/writer and producer, with Rachel Talbot, of HOLLYWOOD, DC: A TALE OF TWO CITIES (Bravo).