by Anna Maria Gillis

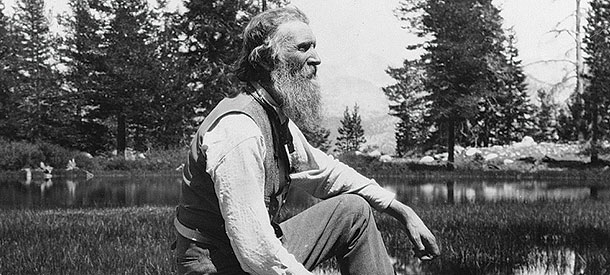

In September 1865, John Muir wrote to a friend, “How intensely I desire to be a Humboldt!” At the time, it must have seemed a pipe dream. A pacifist opposed to the Civil War, the twenty-seven-year-old Muir had left his family’s Wisconsin farm the previous year and traveled to Michigan. From there, he crossed the Canadian border and kept walking east. Now, the future forefather of American conservationists and savior of Yosemite found himself making broom handles and rakes in Meaford, Ontario, about as far removed as he could have been from the Latin American tropics made famous by the great German explorer Alexander von Humboldt.

Muir’s journey from machinist to scientist, writer, and activist—and some would say icon—was aided by a host of nineteenth-century luminaries. He walked California’s Mount Shasta with Asa Gray, the Harvard botanist who was Charles Darwin’s greatest American explicator, and communed with Ralph Waldo Emerson in Yosemite’s Mariposa Grove. Robert Underwood Johnson of The Century Magazine was his editor, taskmaster, and friend. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft traveled Yosemite with Muir, and the railroad magnate Edward Harriman hosted him on a scientific survey of Alaska. But the person who cultivated Muir’s potential and who prodded him to become an explorer in his own right was Jeanne Carr, the recipient of the Humboldt letter.

Carr met Muir in 1860 while she was judging the state fair in Madison, Wisconsin. When he wasn’t toiling in his father Daniel’s fields, Muir spent his late adolescence inventing all manner of things: a field thermometer, a gadget that would tip him out of bed in the morning, and a model for automating the sawing of logs. With the nudging of a neighbor, Muir showed some of his inventions in the Madison fair. Although they were well received, Muir, remembering his hellfire Scottish father’s admonishment to avoid praise, did not save the newspaper reports. In his memoirs, Muir recalled that “father carefully taught us to consider ourselves very poor worms of the dust, conceived in sin, etc., and devoutly believed that quenching every spark of pride and self-confidence was a sacred duty, without realizing that in so doing he might at the same time be quenching everything else. Praise he considered most venomous.”

In contrast, Jeanne Carr saw a promising young man, who, despite his haphazard early education, was meant to be more than a laborer. She and her husband, Ezra, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, encouraged him as he began to follow his inclinations toward botany and geology. Although Muir left the university without taking a degree, he continued his field studies in botany and sent his scientific musings to his Madison connections, particularly Jeanne. Her role in developing his potential is highlighted in John Muir in the New World, a new PBS documentary. “She gave [Muir] confidence that he could become something,” says University of Kansas environmental historian Donald Worster in the film.

Initially, Muir had stilled the inner voice calling him to a life of exploration and used his considerable skills to improve productivity in the Canadian broom factory and later in Indianapolis, where he worked as a sawyer for Osgood, Smith & Co. There, a file slipped out of his hand and blinded him—it turned out temporarily—making him despondent and forcing him to reconsider what he wanted to do. Telling him not to be anxious, Carr wrote, “I have often in my heart wondered what God was training you for. He gave you the eye within the eye, to see in all natural objects the realized ideas of His mind. . . . He will surely place you where your work is.”

Intent on getting to South America, Muir gave up his job, took his savings, and, in the fall of 1867, began walking mile after mile, collecting plants and observing the rise and fall of the land from Louisville to Florida, where malaria felled him. Without being fully recovered, Muir moved on to Cuba, like Humboldt. But illness, heat, and humidity became oppressive, so Muir changed course. He hopped on a boat carrying oranges from Havana to New York, and from there headed to California and into the Sierra Nevada and its Yosemite Valley, where he took manual jobs as a sawyer and a sheep herder so he might study the magnificent landscape. Entranced by the peaks, trees, and waters in what he eventually called “the Range of Light,” he told Carr that he was “feasting in the Lord’s mountain house.”

It’s on his journey of scientific inquiry, first to the Gulf and in his first summer in the Sierra Nevada, that Muir’s religious thinking evolves, and he leaves much of his Calvinist background behind, says Worster.

A man of his time, Muir was raised with the view from Genesis that God has given man dominion over all of nature. But in A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf, based on his journals from that period published posthumously in 1916, Muir adopts a humbler view: “The world, we are told, was made especially for man—a presumption not supported by all the facts. A numerous class of men are painfully astonished whenever they find anything, living or dead, in all God’s universe, which they cannot eat or render in some way what they call useful to themselves.” He goes on to say, “From the dust of the earth, from the common elementary fund, the Creator has made Homo sapiens. From the same material he has made every other creature, however noxious and insignificant to us. They are earth-born companions and our fellow mortals. The fearfully good, the orthodox, of this laborious patchwork of modern civilization cry ‘Heresy’ on every one whose sympathies reach a single hair’s breadth beyond the boundary epidermis of our own species.”

Other nineteenth-century thinkers—Humboldt, Emerson, Thoreau, Ruskin—looked at nature for inspiration, and Muir knew their work, but Muir went further. He may be regarded, says Worster in an interview, “as a religious prophet,” one whose religion was Nature.

At the same time, Muir fully remained a man of science, determined to “entice people to look at Nature’s loveliness.” In A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, Worster explained, “More than ever, he saw that his method of opening others’ eyes must be through scientific exploration and scientific explanation. The beauty of the natural world would be revealed though an immersion in facts and mechanics.”

In the summer of 1871, the Smithsonian Institution asked Muir to send along reports of what he discovered on his walks in California’s high peaks. Within months, Muir discovered glaciers in the Sierra Nevada and soon began measuring them, and in December reported his findings in the New-York Tribune: “The great valley itself, together with all of its various domes and walls, was brought forth and fashioned by a grand combination of glaciers, acting in certain directions against granite of peculiar physical structure.” Although time has proved Muir more right than wrong, the professional geology community, still a young discipline, was mixed in its response to an amateur geologist’s claim that Yosemite had glacial origins; and his father found no merit at all in the work.

“Yosemite Glaciers” was Muir’s first published essay. Within the year, he began contributing articles to Overland Monthly (California’s answer to the Atlantic Monthly) and other publications. A mix of natural history, geology, and adventures worthy of the modern magazine Outside, Muir gave armchair naturalists the “inexpressible joy experienced by every explorer in nature’s untrodden wilds” without having to deal with the animals, avalanches, and the violent storms common at high elevations.

Muir traveled light. On a mountain he carried tea and a bit of bread and little else, confident that he was safe with Nature. In his wanderings, he got himself into some sticky situations, says Worster, and it is amazing he survived.

By 1876, Muir was calling in his writings for better management of Yosemite, which was being overgrazed and heavily logged. Reporting in the Sacramento Daily Record-Union that “waste and pure destruction are already taking place at a terrible rate” in the Sierras, he wrote in terms that sound strikingly contemporary: “The practical importance of the preservation of our forests is augmented by their relations to climate, soil and streams.”

For the next decade, Muir wrote little. He married Louie Strentzel—Jeanne Carr was the matchmaker—in 1880, and, with the exception of forays to Alaska to study its glaciers and people, Muir stayed close to home, doting on his daughters and running his father-in-law’s fruit farm at a good profit.

But in 1889, with Louie’s blessing, Robert Underwood Johnson drew him back into the literary world. On a camping trip in Yosemite’s high country, Johnson convinced Muir that he was just the person to lead the still-tiny conservation movement in arguing for national park status for Yosemite. Johnson promised that if Muir wrote for The Century, the influential East Coast editor would make sure the ‘right people’ read his essays.

In “Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park,” which appeared in September 1890, Muir took readers through the landscape like a friendly tour guide, mapping out an area for protection and letting them know that William Vandever of California has introduced a bill to protect the region. In much milder language than he used later, Muir simply said, “Unless reserved or protected the whole region will soon or late be devastated by lumbermen and sheepmen, and so of course be made unfit for use as a pleasure ground.”

Congress moved quickly and even expanded Yosemite’s size; President Benjamin Harrison signed the act into law on October 1, 1890. Turning Yosemite into a national park was a short sortie compared with the fights Muir would lead up until his death. Along the way, some of the men he considered friends would fall away, and the young conservation movement would experience a schism that is today expressed in battles over spotted owls in Oregon, wolves in Yellowstone, and the use of public lands generally.

As Muir’s fame grew, he was asked to preside over the newly formed Sierra Club, and in 1896 he served as an adviser to a forest commission set up by the National Academy of Sciences to determine the condition of the nation’s western forests. Led by Charles Sprague Sargent, a Harvard University botanist, the commission (which also included the up-and-coming Gifford Pinchot, who became the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service) traveled to South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona and Colorado and determined that many forests were in poor shape and needed protection. But how? Sargent wanted forests to be protected by the army, a view that Muir had some sympathy for because the army had already made forays into Yosemite and Yellowstone. Pinchot wanted a professional civilian force. In its report, the commission balanced the Sargent and Pinchot views. It also recommended that reserves totaling more than 20 million acres be set aside as national forests, a suggestion that was approved by President Grover Cleveland and challenged by western politicians.

Muir made his own report in The Atlantic Monthly. “The forests of America, however slighted by man, must have been a great delight to God; for they were the best he ever planted.” He described trees with a diameter of twenty feet as “lordly monarchs proclaiming the gospel of beauty like apostles.”

He reminded his readers of the changes that came with the clearing of the American landscape and wrote, “Every other civilized nation in the world has been compelled to care for its forests, and so must we if waste and destruction are not to go on to the bitter end.”

Even though Muir used a language of reverence, he did not say that the forests and the nation’s natural resources were not to be used. He wrote of America opening itself to “good men of every nation,” who should be “as free to pick gold and gems from the hills, to cut and hew, dig and plant, for homes and bread, as the birds are to pick berries from the wild bushes, and moss and leaves for nests.”

Like a preacher exhorting his congregation, Muir went on to say, “Mere destroyers, however, tree-killers, wool and mutton men, spreading death and confusion in the fairest groves and gardens ever planted,—let the government hasten to cast them out and make an end of them.”

Efforts by Muir and his conservation-minded colleagues received a huge boost when Theodore Roosevelt became president. At Roosevelt’s suggestion, Muir and the president camped together in Yosemite in 1903. The president left convinced that Yosemite should be fully under control of the federal government.

Although Roosevelt extended federal protection to millions of acres of land during his tenure, two of the great conservationists of the twentieth century were not cut from exactly the same cloth.

At the same time Roosevelt was promoting conservation, he was also considering the need for dams and reservoirs and balancing competing political and social needs. Within his administration, Pinchot was a proponent of practicing “wise use”—a term that was not tightly defined—in managing natural resources. If “wise use” meant the selective harvesting of trees, the damming of waterways for irrigation, and sometimes the destruction of wildlife habitat for economic development, then Muir had never been opposed to it, but he drew the line at national parks because they were about “consecrating a small part of nature,” Worster wrote. “For years Muir had gone along with utilitarian conservation, provided that ‘wise use’ included spiritual and aesthetic values, and he was confident that Roosevelt shared his thinking that those values were as important as economic benefits.”

That was not the case when it came to the Hetch Hetchy Valley, a place Muir considered every bit as sublime as Yosemite Valley. As early as 1882, the city of San Francisco was looking to make the valley a reservoir. In 1903, Secretary of the Interior Ethan Hitchcock denied San Francisco’s mayor a permit to store water in the valley because it was within the bounds of a national park. James Phelan, the city’s mayor, continued to petition, but not until the San Francisco earthquake and fire did the matter become urgent.

When Muir learned that James Garfield, Roosevelt’s new Secretary of the Interior (with Pinchot’s encouragement) might approve San Francisco’s request to dam Hetch Hetchy, he launched a campaign that became the first national, all-out organized conservation fight.

Passionate about “pieces of extraordinary nature,” Muir was willing to do whatever it took, says Cornell University historian Aaron Sachs in the film. “All he cared about in this fight was preserving something beautiful and inspirational and sacred, and that came across as impractical. It came across as elitist. People wondered if he would just sacrifice everything about civilization in order to preserve this one little piece of wilderness.”

In a convoluted series of moves and countermoves that played out in the national press through the presidencies of Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson, proponents and opponents argued over the best way to use public land. The film points out how difficult the debate was—everyone, including Muir, recognized that San Francisco needed water. But the question was from where would that water come?

Each side was harsh and alliances were not wholly predictable; the Sierra Club itself was divided. Hetch Hetchy was threatened by “robbers of every degree from Satan to Senators,” wrote Muir. William Kent, a member of the House of Representatives and onetime friend of the conservationist, described him as devoid of social sense: “With him it is me and God and the rock where God put it, and that is the end of the story.”

When Woodrow Wilson in 1913 signed into law the bill allowing a dam in Hetch Hetchy, Muir wrote to a friend: “It is a monumental mistake, but it is more, it is a monumental crime.” In poor health, Muir died the next year.

Over his seventy-six years, Muir transformed not only himself, but the nation. He taught us “to slow down and think about what we are doing,” says Sachs.

Muir once wrote, “I only went out for a walk and finally concluded to stay out till sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in.” He may have set off to be a Humboldt, but, in walking, he became Muir.

Anna Maria Gillis is managing editor of Humanities. Republished from the March/April 2011 issue of Humanities, the magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Used with permission.

John Muir in the New World, which airs April 18 on PBS’s American Masters (check local listings), received major funding from the NEH. John Muir’s Nature Writings, a collection published by The Library of America was helpful in writing this article.