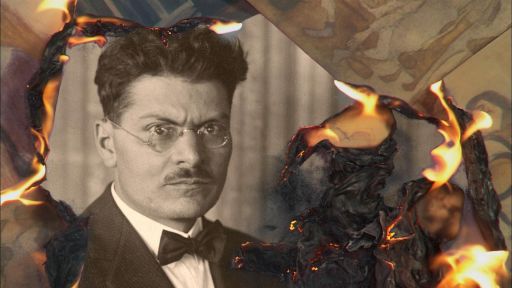

Bold and complex, José Clemente Orozco’s iconoclastic personality and dynamic painting made him the conscience of his generation. A film on his life and his art, Orozco: Man of Fire, is directed, written and produced by Laurie Coyle and Rick Tejada-Flores. Below, Coyle answers some questions about the film and its fascinating subject:

Bold and complex, José Clemente Orozco’s iconoclastic personality and dynamic painting made him the conscience of his generation. A film on his life and his art, Orozco: Man of Fire, is directed, written and produced by Laurie Coyle and Rick Tejada-Flores. Below, Coyle answers some questions about the film and its fascinating subject:

Q: What do you think is Orozco’s most significant cultural contribution?

A: Ultimately, his most significant cultural contribution is the art he created. Orozco was one of the primary artistic innovators of the 20th century. Along with his fellow Mexican muralists, he revived the fresco tradition. Unlike Italian Renaissance frescoes, which celebrated a unified vision of the world and humanity’s place within it, Orozco’s frescos express a modernist sensibility that questions and deconstructs. He forged an original and remarkable synthesis in modern painting: monumental murals imbued with a critical spirit, a savage irony, a terrible beauty. He consistently pushed the boundaries in his choice of subject matter and never shied away from offending. His expressionist style demonstrated a continual and daring formal and thematic progression. Orozco’s abiding legacy is an ambitious and humane vision of the role of art in society.

Q: How did Orozco overcome such tragedies as the loss of a hand and numerous paintings?

A: Irony is the operative word: the more traumatic the experience, the greater Orozco’s emotional detachment. He described the explosion that cost him his left hand “an ordinary childhood accident.” He called the Mexican Revolution “the gayest and most diverting of carnivals” but his artwork belies his true feelings about its horrors. He made a joke about the incident at the U.S.-Mexico border that destroyed most of his early paintings, writing, “I was led to believe that it was against the law to bring immoral drawings into the United States…or that they already had enough of their own.” Actually, the experience shook him to his core, so much so that he didn’t attempt any new paintings during his first two years in the United States.

Orozco had great tenacity and an unshakeable faith in his mission. He was a master painter, a genius really, and yet he faced tremendous obstacles in his long journey of becoming an artist. He didn’t paint his first mural until he was 40 years old. I don’t think many of us can relate to a one-armed artist painting a hundred feet above the ground, but we can relate to Orozco’s very human struggle to become who he really needed to be – that he achieved and that we can all relate to and admire.

Q: Why did fame come more easily to Rivera than Orozco?

A: The rivalry between Rivera and Orozco was essentially one of personalities. Rivera was an extrovert, the ultimate self-promoter who moved comfortably in all social circles, while Orozco was an introvert with a chip on his shoulder. In the early years, he struggled more for recognition. But by the time of his death, Orozco was considered the pre-eminent muralist of his generation, and archrival Rivera called him “the greatest painter Mexico has produced.” He was embraced by American artists, including 1930s muralists like Thomas Hart Benton and Aaron Douglas, as well abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock, and modernists like Isamu Noguchi, Ben Shahn and Jacob Lawrence.

Orozco’s rivalry with Diego Rivera dated from childhood, when both attended Mexico’s premiere fine arts academy. Rivera was the “anointed” student with a scholarship that enabled him to study painting in Paris. Orozco, on the other hand, worked a series of odd jobs during the day to support his family and attended art classes at night. Orozco never studied in Europe and only visited when he was 50 years old and already an established artist.

Q: What drove Orozco to pursue political art and why did he choose murals?

A: Orozco’s life spanned the Mexican Revolution, the Great Depression and the Second World War, and his personality, philosophy and aesthetics were influenced by these cataclysmic events. He believed that the role of art was to bear witness to history, not to illustrate it or celebrate the victors. Orozco sided with the oppressed, but it was not an ideological thing, it came from his life experience and convictions, from his gut. He was skeptical of ideology, but clear in his critique of the destructive potential of the machine, tyranny, militarism and intolerance. In this sense, Orozco takes his place among figures like Francisco Goya, Honoré Daumier, Pablo Picasso, Kathe Kollwitz, and Max Beckmann.

The choice of muralism was essentially one of the historical moment. At the beginning of the 20th century, young Mexican artists were rebelling against academic art. Like the French Impressionists’ Salon des Refusés, they organized an exhibition of independent painting of various modernist tendencies. These artists were also participating in the broader political movements to overthrow the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. When the Mexican Revolution broke out, they put their art on hold for a decade. In the ’20s, these artists came together to create public art that would educate Mexico’s illiterate masses and memorialize the sacrifices of the revolution. Orozco didn’t buy into the propaganda goals of the mural movement, but he used the broad canvas of murals to create works that were deeply personal yet universal in their intensity and power. His statement about mural painting says it best: “The highest, the most logical, the purest and strongest form of painting is the mural. It is also the most disinterested form, for it cannot be made a matter of private gain; it cannot be hidden away for the benefit of a certain privileged few. It is for the people. It is for ALL.”

Q: What inspired you to make a film about Orozco?

A: In the 1970s as young art students, we both made pilgrimages to the great murals of Mexico. We were drawn to their vision of a social role for art. More than the others, the murals of José Clemente Orozco drew us back again and again. There was something daring about his compositions, dark in their meanings, risky in their style. His work evoked the sublime El Greco; inhabited the moral universe of Francisco Goya; resonated with its contemporary across the Atlantic, German Expressionism. Orozco bridged a chasm between the socially conscious revolutionary art of the 1930s, the abstract expressionism of the Cold War, and the conceptual formalism of the post-’60s artists.

But Orozco the man was an enigma. On a research trip to Mexico, we scoured bookstores for sources but the results were disheartening: the average art section carried five titles about David Alfaro Siqueiros, 10 on Rivera, and even more about the recently idolized Frida Kahlo (selling a large selection of memorabilia including clay Frida figurines). As for books about Orozco, we usually found none at all. But piecing his life together from out-of-print books, conversations with people who had known him and his own writings, we discovered one of the great, untold stories of modern art, filled with drama, adversity and remarkable achievement.

Q: Tell us about the way you employed graphics in the film.

A: We didn’t want to make a conventional bio-pic about Orozco, so the challenge was to create a documentary style that evoked Orozco’s irony and irreverence, as well as the beauty of his art. We had written these visual sequences that were not naturalistic. We wanted to animate Orozco’s wit, and work with folk art, vintage photos, memorabilia and props. It was very difficult to find the right visual effects artist, because the work samples we saw were so slick. When film producer Sue West introduced us to Robert Conner, we knew he was the one. He brought a lyricism and whimsy to the compositions, and he got Orozco intuitively. We shot some elements in blue screen and collected the rest from archival sources, junk shops and flea markets in Mexico City. Robert constructed the tableaux in Photoshop and After Effects. Whenever he sent us a rough sample, we would throw it up on the office computer, everyone would gather around, and we would laugh in delight and wonder. It was the highlight of the week.

Q: What are some of the central themes Orozco embraced in his art?

A: Orozco once wrote, “I believe in criticism as the most penetrating mission of the spirit, and in its expressive power in art.” He maintained a resolutely critical stance on every theme he tackled, especially the corrupting influence of power and the tyranny of belief systems, whether religious or political. He regarded all orthodoxies or “isms” of the 20th century with equal disdain, his antipathy for ideology matched only by his compassion for common people caught in the great conflagrations of his times. Early in his career, Orozco’s focus was political caricature. He always retained this focus on social satire, although his style evolved into expressionism, and he became what a contemporary called, “the only tragic poet of the Americas.” Especially after his years in the United States, Orozco’s work became increasingly universal and allegorical. He was a humanist concerned with good and evil, with a spiritual quest for meaning, if you can say that about an agnostic.

Q: Did Orozco have conflicted feelings about the Mexican Revolution?

A: Orozco was profoundly suspicious of romanticizing the Mexican Revolution, or any other revolution for that matter. In this regard, he differed from his more overtly political colleagues Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The loss of his hand through an accident saved him from forced conscription in the warring armies of the revolution. During those years he worked as a political cartoonist, creating biting and satirical images for a series of opposition newspapers. But he was unwilling to cross the line to exhort anyone to kill or be killed for abstract ideas, which seemed to him to mask the baser motives of greed and the pursuit of power. In the years that followed, he produced a series, Mexico in Revolution, that ranks with Goya’s Disasters as one of our most powerful testimonies to the tragedy of war.

Q: Is the art of social realism being practiced today and, if so, are the artists at all indebted to Orozco?

A: Social realism isn’t really a style, but refers to a tendency in art to explore social conditions, to use art as a weapon in struggles against injustice. It’s often confused with “socialist realism” and Soviet-inspired art after the Russian Revolution. Social realism had its big moment in U.S. art between the World Wars, and again in the ’60s. Both eras had a strong focus on mural painting because of its public nature. It incorporates a very broad range of genres and styles, which can easily be seen in the art created under the WPA programs during the Depression. The Mexican Mural Renaissance was never a stylistic movement like Cubism or Fauvism. It incorporated everything from Diego Rivera’s neoclassical epic style, to David Alfaro Siqueiros’ structural dynamism and Orozco’s expressionism.

When the U.S. community mural movement began in the ’60s, Orozco was over-shadowed by Rivera and Siqueiros. Rivera’s bold and sensual forms, and Siqueiros’ iconic revolutionary images better suited the spirit of Chicano pride and protest. Orozco’s style was enigmatic and inimitable – and he wasn’t married to Frida Kahlo! He had a subtler but equally important influence that can be described as both a moral influence and one of gesture. Orozco represented the artist as solitary individual who offers a unique and powerful response to his times. His artwork never goes out of style.

Q: Why is Orozco an American Master?

A: In the first place, it’s important to point out that most people living in the continents north and south call themselves “Americans” and don’t embrace the notion that “America” refers to the United States. So from that point of view, of course Orozco is an American Master.

Beyond geo-politics and national identity, Orozco spent 10 years in the United States, where he painted four major murals as well as hundreds of easel paintings and graphic works. He challenged stereotypes of Mexican art as folkloric, exotic and social realist, and became a vital member of the New York art scene. During his years in the U.S., Orozco faced episodes of censorship, but transcended cultural and language barriers to become a pioneer of the public arts movement of the 1930s-40s. His expressionist style influenced successive generations of American artists – the young Jackson Pollock kept a photograph of Orozco’s Prometheus mural in his studio, and declared it to be “the greatest painting in North America.” Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish and Charles White traveled to Mexico to watch him paint. Ben Shahn, Hale Woodruff, Jacob Lawrence, and Isamu Noguchi absorbed stylistic influences, as did the generation of Chicano and African-American muralists who reinvented public art in their communities in the 1960s-1970s. Today, his legacy inspires contemporary conceptual artists on both sides of the border.