Edward Hopper is our great American artist of nostalgia.

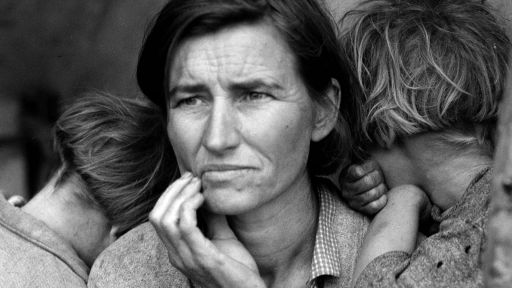

More even than his slightly younger contemporaries Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Ansel Adams (1902-1984), Walker Evans (1903-1975) and Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009), Hopper has imprinted the contents of his haunted imagination upon the psyche of America: a lifelong fascination with the beauty suffusing the very banality of American life. Entering Hopper’s familiar but uncanny world, we fall at once under his spell.

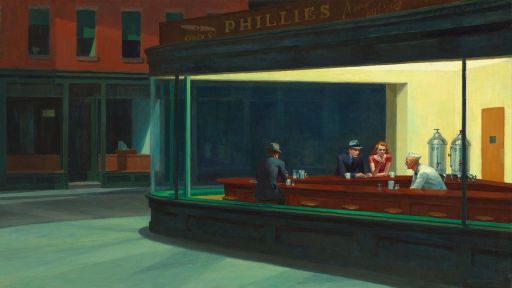

As powerful a sensation as nostalgia is déja vu—the unnerving conviction that we have been here before and we have seen this before; we have been these people. For Hopper’s dreamlike figures inhabit a netherworld recognizable as the past; but it is not a turbulent, troubled, divisive, anguished past, not a richly romanticized past, nor the past of heroic struggle, but rather the past of warmly selective memory—the all-night diner surrounded by darkness of “Nighthawks” (1942); the surpassingly beautiful soft-red-brick façade of storefronts (with barber pole) of “Early Sunday Morning” (1930); the near-deserted rural Mobil gas station at dusk of “Gas” (1940) with its trio of gas pumps and lone attendant incongruously dressed in long-sleeved shirt, vest, necktie as if he were an urban dweller, possibly accountant, a surrogate for the artist (or the viewer).

Hopper’s human figures are likely to be solitary, frozen in place, their faces empty of expression even as their bodies are captured in postures of sheer longing, a yearning for something out of reach, unseeable within the (confining) frame of the artwork, inexpressible. Because these mannequin-figures lack specificity, we identify emotionally with them—they could be anyone, they could be us, ageless, near-anonymous, seated in chairs, on the edges of beds, gazing through windows, gazing at the sky, at the sea, into oblivion; standing alone in the doorway of a white clapboard house lost in memory; sitting (awkwardly, uncomfortably) in lawn chairs facing the sun, captured in eternal expectation, transfixed.

Hopper’s human figures are likely to be solitary, frozen in place, their faces empty of expression even as their bodies are captured in postures of sheer longing, a yearning for something out of reach, unseeable within the (confining) frame of the artwork, inexpressible. Because these mannequin-figures lack specificity, we identify emotionally with them—they could be anyone, they could be us, ageless, near-anonymous, seated in chairs, on the edges of beds, gazing through windows, gazing at the sky, at the sea, into oblivion; standing alone in the doorway of a white clapboard house lost in memory; sitting (awkwardly, uncomfortably) in lawn chairs facing the sun, captured in eternal expectation, transfixed.

If they/we happen to inhabit a space with other figures, they/we do not look at one another, or even seem aware of each other, as (Hopper may have felt despite his long marriage to an artist who was also his frequent model) we find ourselves in close physical proximity with strangers in settings that are domestic, even intimate. The very titles of such works of Hopper are both generic and evocative: “Eleven A.M.” (1926), “Night Windows” (1928), “August in the City” (1945), “City Sunlight” (1954), “A Woman in the Sun” (1961), “High Noon” (1949).

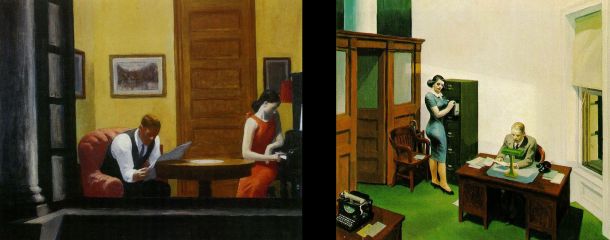

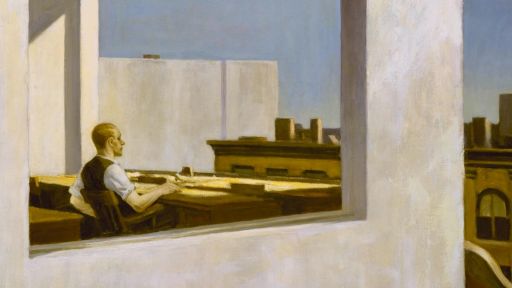

Frequently, in scenes reminiscent of stills from films, including film noir, the artist positions himself, and the viewer, in the role of voyeur—peering through windows into private lives, sometimes into lighted interiors, in such paintings as “New York Office” (1962), “Room in New York” (1932), “Night Windows” (1928), “Office in a Small City” (1953), “Cape Cod Morning” (1950). Startlingly intimate scenes as in “Room in New York” and the thematically related “Office at Night” (1940) hint at unarticulated erotic yearning (female) in the presence of a seemingly indifferent companion (male).

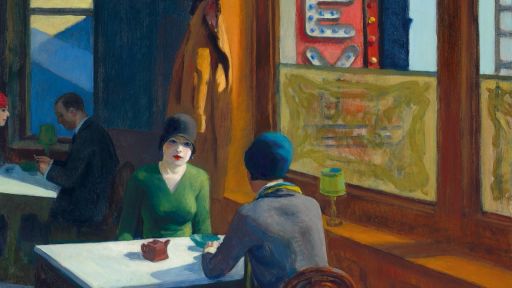

In the former, a woman is seated uncomfortably at a piano, picking idly at the keys as her husband ignores her, concentrating on a newspaper; in the latter, a young woman secretary in an unusually form-fitting dress is turned covertly, perhaps wistfully, observing her boss seated at his desk, indifferent to her presence. (In contrast, we have the singular “Sunlight in a Cafeteria” [1958], in which an attractive young woman sits alone at a restaurant table while at the extreme right a ghastly-pale man stares at her with an erotic intensity unusual in Hopper, his uplifted hand extended toward her, unseen by her—an alarmingly thin, even skeletal hand.) Even in these intensely intimate scenes in which the artist and the viewer seem to have merged, there is no sense of Hopper exploiting or subverting his subjects, but rather honoring the mysterious and inaccessible inwardness of others.

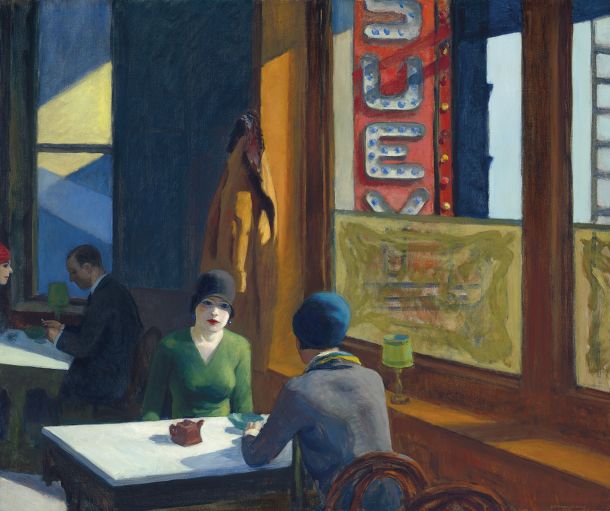

Hopper’s predominant interest in painting was in light, the play of light and shadow in the visual field, rendered in paintings of dazzling technical virtuosity and emotional power. Once the viewer is aware that light is Hopper’s formal concern, it is fascinating to see how the artist bathes scenes in sunlight which is qualified, modified, transformed by shadows that vary in sharpness and size. These range from the relatively straightforward paintings “Sunlight in a Cafeteria” and “City Sunlight” (1954) to the beautifully rendered “Cape Cod Afternoon” (1936), “South Carolina Morning” (1955), “Sun in an Empty Room” (1963), “A Woman in the Sun” (1961)—(nude woman lost in thought, unmade bed behind her, window opening onto a blurred landscape, framed art-work on the wall as blurred as a dream image).

Hopper’s predominant interest in painting was in light, the play of light and shadow in the visual field, rendered in paintings of dazzling technical virtuosity and emotional power. Once the viewer is aware that light is Hopper’s formal concern, it is fascinating to see how the artist bathes scenes in sunlight which is qualified, modified, transformed by shadows that vary in sharpness and size. These range from the relatively straightforward paintings “Sunlight in a Cafeteria” and “City Sunlight” (1954) to the beautifully rendered “Cape Cod Afternoon” (1936), “South Carolina Morning” (1955), “Sun in an Empty Room” (1963), “A Woman in the Sun” (1961)—(nude woman lost in thought, unmade bed behind her, window opening onto a blurred landscape, framed art-work on the wall as blurred as a dream image).

(It should be noted how sympathetic Edward Hopper is in depicting women: they are likely to be attractively, colorfully dressed, while his male figures, emblems of middle-class convention, are dressed in dull, neutral colors and often appear slumped, lifeless.) Hopper’s lethargic male figures may be projections of his own sense of himself as socially limited, even reclusive; it was said of Hopper that “he had no small talk”—“he was famous for monumental silences.” In his own words: “If you could say it in words, there’d be no reason to paint.” 3

William Wordsworth spoke of poetry as “emotion recollected in tranquility”—an ideal definition of Edward Hopper’s unique work. There is a ravishing sensuousness to his most memorable paintings which has to be seen first-hand to be truly appreciated—such paintings as “Morning in a City” in which a nude young woman pauses in her dressing, to gaze dreamily out a window; “Eleven A.M.” (1926), another nude study in which a young woman gazes out a window with her face averted, in a posture poised between expectation and resignation; “Girl at a Sewing Machine” (1921), in which a mood of exquisite sensuousness is suggested in the rich flesh color of a wall behind a seated girl oblivious of her surroundings.

In the tenderly observed “Summer Evening” (1947), a young couple in casual summer clothing is standing close to each other on a lighted porch in a pose that, unusual in Hopper, seems naturally intimate, affectionate; though the darkness that surrounds them is just slightly ominous, the colors of the porch are quietly luminous.

In the tenderly observed “Summer Evening” (1947), a young couple in casual summer clothing is standing close to each other on a lighted porch in a pose that, unusual in Hopper, seems naturally intimate, affectionate; though the darkness that surrounds them is just slightly ominous, the colors of the porch are quietly luminous.

What Hopper meant by light seems to have been a kind of spiritual radiance that flows in and around and through his subjects, rendering their very ordinariness extraordinary, magical; it is a secular vision, yet in its way sacred, elevating and not debasing, in a way difficult to define as quintessentially American.

FOOTNOTES