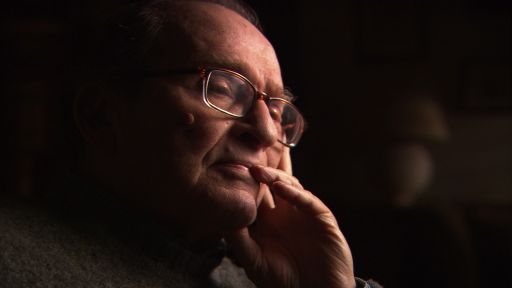

By filmmaker Marilyn Mellowes, director of American Masters: Julia Child! America’s Favorite Chef.

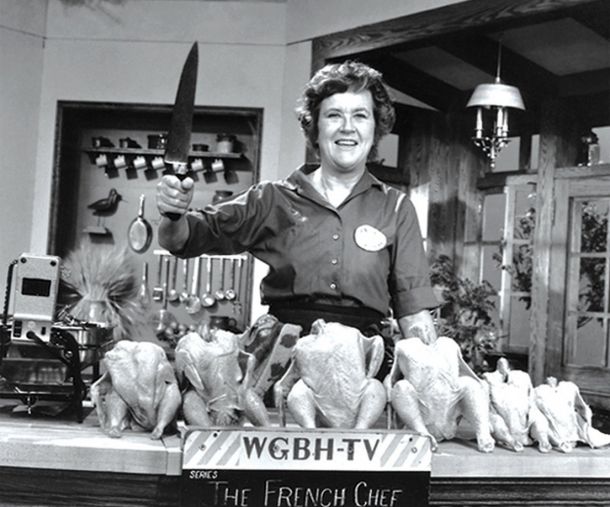

Scooping up a potato pancake, patting chickens, coaxing a reluctant soufflé, or rescuing a curdled sauce, Julia Child was never afraid of making mistakes. “Remember, if you are alone in the kitchen, who is going to see you?” she reassured her television audience. Catapulted to fame as the host of the series The French Chef, Julia was an unlikely star. Over 6′ 2″, middle aged and not conventionally pretty, Julia had a voice careened effortlessly over an octave and could make an aspic shimmy. She was prone to say things like “Horray” and “Yum, yum.” Her early culinary attempts had been near disasters, but once she learned to cook, her passion for cooking and her devotion to teaching, brought her into the hearts of millions and ultimately made her an American icon. To the fans who knew and loved her, she was known simply as Joooolia.

Julia Child on WGBH. Photo: Paul Child/PBS

Julia Child’s early life

Born in 1912 in Pasadena, California, she led a life of ease and privilege. She graduated from Smith College with vague aspirations of becoming a writer, but never found a focus. She confided in her diary: “I am sadly an ordinary person… with talents I do not use.” Yet she continued to yearn for adventure and the chance to escape from her comfortable upper middle class existence.

She found that chance in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Like many Americans her age, she hurried to Washington to work for the war effort, finding a job at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Eventually she volunteered to go to the Near East. In March 1944, she set sail for Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, to work for the OSS office in the ancient city of Kandy. Here, far from home, she finally had her chance for adventure – and for love.

But it was not love at first sight. Ten years older than Julia, Paul Child was an artist, a poet who had earned a black belt in judo, traveled the world, and spoke flawless French. Shortly after meeting Julia he wrote to his twin brother Charlie, that Julia was “wildly emotional” and “an extremely sloppy thinker” who was “unable to sustain ideas for long.” Julia, for her part, was disappointed in Paul, whom she described as having “light hair which is not on top, an unbecoming blond mustache and a long unbecoming nose.” But very slowly and over time, the two fell quietly in love. In the summer of 1946, they traveled across the country together, accompanied by 8 bottles of whiskey, a bottle of gin and a bottle of mixed martinis. Paul wrote to Charlie, “(Julia) never ‘puts on an act’, or creates a scene. . . She frankly likes to eat and use her senses and has an unusually keen nose.” In another letter he reported “She also washes my shirts! Quite a dame!” They were married that September.

Julia Child’s time in France

Paul, who worked for the State Department, was soon posted to France. En route to Paris, Paul took Julia to the oldest restaurant in the country, La Couronne. This was her first experience with classical French cuisine and she fell in love. “The whole experience was an opening up of the soul and spirit for me . . . I was hooked, and for life, as it turned out.” Eager to learn how to make this food, Julia enrolled in the famed Cordon Bleu. Between classes, she studied French and roamed the open air markets, talking with fish mongers, bakers and fruit sellers. She and Paul scoured the neighborhoods of Paris for friendly bistros, and under her husband’s patient tutelage, Julia’s palette grew more and more sophisticated.

It was in Paris that Julia met two French women, Simca Beck and Louisette Bertholle, who were writing a cookbook aimed at an American audience. They needed an American collaborator. Julia was perfectly suited for the job. She began testing recipes. For nearly ten years, she devoted herself to writing, testing and re-writing. She confided to her sister-in-law: “Really, the more I cook the more I like to cook. To think it has taken me 40 yrs. To find my true passion (cat and husb. excepted).”

Simca emerged as her principal collaborator. As Paul and Julia were posted from Paris to Marseilles to Bonn to Oslo and on to Washington, they kept up a furious correspondence, typing hundreds of letters with six carbon copies. Julia kept meticulous notes and spent months perfecting recipes for one ingredient. She made so many egg dishes that she finally wrote to Simca, “I’ve just poached two more eggs and throw them down the toilet.” When the women finally submitted their manuscript, the publisher turned it down. They made major revisions. Again, the publisher turned it down. “Hell and damnation,” Julia wrote to Simca. After repeated rejections, the book was finally picked up by a new publisher, Alfred Knopf and nurtured by a young and talented editor, Judith Jones. In 1961, Julia finally held in her hands the book titled “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” It had taken ten long years of relentless toil to produce. But it was not clear how the book would be received in America.

PBS and The French Chef

Now living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Julia would soon find out. She was invited to appear on a television program called “I’ve Been Reading”, produced by WGBH, Boston’s public television station. The host of the show was reluctant to take time for a subject as trivial as cooking. But Julia was undeterred. She arrived with a hot plate, giant whisk and eggs, and made an omelet. Twenty-seven viewers wrote to the station, wanting to see more. The station produced three pilots, then launched into production of The French Chef. Produced and directed by Russ Morash, the series broadcast a total of 199 programs, produced between 1963 and 1966.

Julia’s timing was perfect. More and more Americans were traveling abroad. The Kennedys were in the White House. The majority of middle class women had not yet joined the work force; the bored housewife syndrome had not yet been diagnosed as a national malaise. For women who admired Jackie Kennedy chic, Julia’s translation of French cuisine offered a way to acquire a taste of French sophistication. Soon a nation fed mindlessly on Shake n’ Bake, RediWhip and Tang began experimenting with quiche Lorraine, boeuf bourgignon, and reine de saba. Upwardly mobile Americans who regarded cooking as a waste of time, were suddenly seizing whisks, molds and copper bowls, transforming the kitchen into the most important room in the house and making cooking a national pastime.

On camera, Julia’s presence was relaxed, reassuring and informal. But behind the unpolished quirky charm was a driven perfectionist, convinced that there was a right and a wrong way to do things. Working closely with Paul and her associate producer Ruth Lockwood, Julia spent as many as 19 hours preparing for each half-hour segment. Detailed notes described every move she had to make. Her producer wrote out idiot cards that read “Stop gasping.” “Wipe brow.” The camera wore a helpful sign “Me camera.” The audience loved it. So did the critics. One newspaper called her “television’s most reliable female discovery since Lassie.”

By the end of 1965, The French Chef was carried by 96 PBS stations. Sales of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” were picking up speed – 200,000 copies sold. In 1965, Julia won a Peabody. In 1966, she won an Emmy. Time put her on the cover in a feature article on American food – “Everyone’s in the Kitchen.” In December 1966, Julia and Paul spent their first Christmas at La Pitchoune, a country house they built in Provence with royalties from the sales of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” Here they shopped for bread and meat at the local “boulanger.” They cured olives from their own trees. Around them, fields of roses and jasmine filled the air with perfume, along with violets and mimosa. For the next twenty years, Julia and Paul would escape to “La Peetch” as they called it. In this place, so reminiscent of California, Julia rested, worked and wrote. By Christmas 1967, she was busy correcting proofs of The French Chef Cookbook, based on the television series. Reveling in domestic bliss, Paul wrote to his brother: “How fortunate we are at this moment in our lives! Each doing what he most wants, in a marvelously adapted place, close to each other, superbly fed and housed, with excellent health, and few interruptions.”

But Julia’s health was not good. “Left breast off,” she wrote in her date book for February 18, 1968. Back in Boston, a routine biopsy called for a full, radical mastectomy. She stayed ten days in the hospital. Paul was devastated by the specter of cancer and the fear that he might lose her. Julia was stoic. But released from the hospital, she crept into a bathtub and wept. Soon public tragedy eclipsed private sorrows. Martin Luther King was killed. Bobby Kennedy was shot. Julia and Paul, now back in France, heard the news on their tiny transistor radio. Julia was devastated. In Provence, the church bells tolled. Riots broke out at the Democratic convention in Chicago. The times recalled the poetic lament, “The center cannot hold.”

Julia focused her energies on completing Volume II of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” “Rushing from stove to typewriter like a mad hen,” she wrote. She was determined that this book must be “better and different.” The publisher’s deadline was pushed back repeatedly. Once again, she was locked up in a room; she wrote to her friend Avis DeVoto: “I have no desire to get into another big book like Vol II for a long time to come, if ever. Too much work. I am anxious to get back into TV teaching, and out of this little room with the typewriter. Screw it.”

She got her wish. In 1970, after a four year hiatus, Julia returned to film more episodes of “The French Chef” — this time in color. Commercial television had competed for her talents, but she refused to be bought. “I’ll stick with the educators,” she said.

Fans packed her cooking demonstrations. Talk show hosts clamored to interview her. She appeared with the Boston Symphony. She was feted at the Four Seasons. By now Julia had become a celebrity, and Paul reveled in his wife’s success. But Paul was suffering from chest pains. He underwent a coronary bypass. During the surgery, he suffered several small strokes. The strokes had affected his brain. He completely lost his French and verbal fluency. “Whatever it is, I will do it,” Paul had said. He had acted as her manager, served as her photographer, tested her recipes, proof-read her books, and was content to let the light shine on her, not on him. Now, the man that Julia had counted on for so much would need her support in his struggle to survive. Julia gave freely and fully. She did not spend time lamenting their fate. She did what she always did in times of crisis. She moved on.

But the world in which Julia moved was changing — Vietnam, Watergate and the resignation of Richard Nixon. So, too, was the world of food. By the 1970s, a new generation of younger chefs was tossing aside traditional ways, discovering American ingredients and experimenting with new approaches that stressed regional influences, strong flavors, and fresh ingredients. The classic French cuisine that Julia loved so well now seemed slightly quaint. Julia never gave up her fondness for the classic style, but she encouraged the new up-and-coming generation, including Boston-based chefs Jasper White and Gordon Hammersly.

Traditionally, chefs had labored in obscurity, behind closed doors. Julia was determined to change this. She labored tirelessly to promote the profession, and as a result of her efforts, chefs began to receive the recognition they deserved. Now they emerged as celebrities and food became a form of entertainment. Seated at their tables, restaurant patrons could vicariously participate in unfolding drama of food preparation – bread pulled from brick ovens, chickens roasting on spits, vegetables tossed in open skillets. Julia was pleased that chefs were finally getting the attention they deserved, but she disliked the social snobbery that sometimes accompanied celebrity. She wrote to her friend and collaborator Simca Beck, “Food is getting too much publicity and is becoming too much of a status symbol and ‘in’ business.”

Julia herself had shed what she called “the French straight jacket.” In her new series, Julia Child & Company and Julia and More Company, she moved with the times. In 1983, twenty years after the anniversary of The French Chef, Julia launched Dinner at Julia’s filmed at the Swank Hope Ranch, just outside Santa Barbara. Here she was cast in the role of a glamorous hostess, not the familiar, slightly eccentric cook that her fans had come to love. Many found the series disappointing and disconcerting. Julia seemed to shrug it off. She had made her mark. At this point most people would have been ready to retire.

Cooking Collaboration

But not Julia. She wrote a big new cookbook, “The Way to Cook”, accompanied by a home video series. In her late 70s and 80s, she collaborated with a young talented director and producer, Geof Drummond, to make four new series — “Cooking with Master Chefs,” “In Julia’s Kitchen with Master Chefs,” “Baking with Julia,” and with her good friend Jacques Pépin, “Jacques and Julia at Home.” Each series was accompanied by a companion book.

In 1992, Julia’s contribution to food and cooking in America was celebrated on the occasion of her 80th birthday. Three huge parties were held in her honor in Boston, Los Angeles and New York. Honors continued the following year, when Harvard University granted Julia an honorary doctorate. Her citation read “A Harvard friend and neighbor who has filled the air with common sense and uncommon scents. Long may her soufflés rise.” The audience responded with thunderous applause.

Yet one person was not there to celebrate her success. Since 1989, Paul Child had been confined to a nursing home. His once robust body had grown frail and withered. On the evening of May 12, 1994, he passed away.

For six more years, Julia continued to live alone in the house that she and Paul had shared. But she grew weary of New England winters and yearned for the warmth of the California sun. In November 2001, Julia moved to Santa Barbara. Her kitchen was moved to Washington, D.C. The place where she had chopped, stirred and sautéed for forty years is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution. Her pots and pans, her knives and kitchen tools proudly proclaim a culinary revolution that transformed the way that Americans cook, eat and think about food.

Julia Child died just two days before her 92nd birthday, on August 13, 2004, surrounded by her family and friends. The nation mourned her passing, still remembering her with affection and fondness – not simply for her contribution to American cooking, but for who she was: a deeply generous person, open to experience, eager to learn and to teach. The young and restless woman who once mourned her lack of talent became an American icon, and in countless kitchens across the country and around the world, her spirit still lives on. Bon Appetit!

To order a DVD of Julia Child! America’s Favorite Chef, please visit the American Masters Shop.

Major funding for Julia! America’s Favorite Chef is provided by Feast it Forward.

Major support for American Masters is provided by AARP. Additional funding is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Rosalind P. Walter, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, Judith and Burton Resnick, Ellen and James S. Marcus, Vital Projects Fund, Lillian Goldman Programming Endowment, The Blanche & Irving Laurie Foundation, Cheryl and Philip Milstein Family, The André and Elizabeth Kertész Foundation, Michael & Helen Schaffer Foundation and public television viewers.