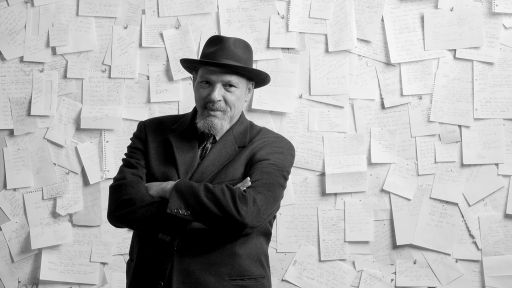

AMERICAN MASTERS Online presents an interview with “Juilliard” filmmaker Maro Chermayeff.

INTRODUCTION

I spent almost every waking minute for two years, crouched in the cubicle-ridden hallways of Thirteen/WNET — my “home away from home” — making the film JUILLIARD and co-authoring the companion book. My partners in crime were the relentlessly talented Susan Lacy and my tireless co-producer, co-author, and co-conspirator Amy Schewel.

Left for years without food or water, the picture finally locked thanks in great part to the wonderful editor Karen Sim and night owl/associate producer Michael Weingrad. The companion volume came next and ultimately went to the printer in Italy this fall, thanks to Harriet Whelchel, the strong-arm “editor” at Harry N. Abrams Inc.

As I hit the streets and faced the daylight after the film’s completion (my eye squinted only a little bit) I enjoyed my freedom for about five minutes before I started to miss all the great Juilliard minds and talents, some living and some gone, that I’d spent the last few years documenting. And I wondered if my “real” friends were going to wipe away the impact made by the likes of John Houseman, Jose Limon, Antony Tudor, Martha Graham, Kevin Kline, James Levine, and Van Cliburn, my “Juilliard” friends.

As the saying goes: I give “sham”pagne to my real friends and real pain to my sham friends!

With this in mind I decided that to help me deal with the separation anixety, I would let my subjects turn the table on me. They would finally have their chance to ask “the tough questions!” As you can see, I am still suffering from bouts of illusion and disillusion. None of these people asked me any of these questions, but it was a fun exercise nonetheless.

So keep in mind, the following interview is entirely imaginary, but the film and book are very real. So “April Fools” to all of you out there in “web-land”. But don’t forget to turn your dial to PBS and Thirteen/WNET today and every day, and especially on January 29th, 2003, at 9:00 p.m. (check your local listings).

INTERVIEW

Van Cliburn: Will AMERICAN MASTERS be given a ticker tape parade in honor of this great achievement?

Filmmaker, Maro Chermayeff: No, but we do have lovely screenings with wine and cheese and all our friends come. And millions of people can watch the program on television.

Frank Damrosch: As founder of the Institute of Musical Art (now The Juilliard School), I know how difficult it is to fund arts programming. How did this film get made?

MC:: Susan Lacy, the Creator and Executive Producer of AMERICAN MASTERS, had wanted for many years to make a film about The Juilliard School, but the timing had just never been right. After making a smaller piece on Juilliard for the WNET program CITY ARTS, I became entranced with Juilliard and did not want to leave. With this is mind, I went to meet with Susan, who told me she had always wanted to make a film about Juilliard, and she thought it could work. We began almost right there on the spot. It was very exciting because it was the kind of program that could only be made by a series such as AMERICAN MASTERS, which encourages and defines this level of arts programming. It was difficult to tackle at first because of the scope of the project and the reality that there were many masters at Juilliard. Ultimately, the film addressed the history of the school but also included the modern element of following five students over the course of one academic year. The elements are intertwined and framed by a “Greek chorus” of luminous alumni and faculty. The film was produced entirely in-house at WNET/Thirteen for AMERICAN MASTERS.

Leonard Bernstein: I taught Master Classes at Juilliard and was associated with the school for many years, and I know as a conductor how critical it is to bring each instrument together to form a cohesive piece. Can you describe some of the production decisions made in taking on a huge project such as this?

MC:: Early on we all decided that while it was important to bring the nearly hundred-year history of the film to life, we also needed (and the audience would crave) the present day vibrancy of the school. We new that there were many important performing artists, actors, musicians, and dancers who are world famous but who may not be known to the general public as having gone to Juilliard. So, our last element was to include interviews with over fifty great stars of the school, including Leontyne Price, Kevin Kline, Christine Baranski, Laura Linney, James Levine, Pina Bausch, Nadja Salerno Sonnenberg, Audra McDonald, and many more. It is often difficult when making documentaries to do portraits of institutions rather than individuals, so the challenge was not to short shift anyone, not to leave important things out, or dwell on smaller achievements for too long. One of my solutions was to let the story be told by the subjects. To achieve this, many, many people were pre-interviewed so that we could see where the memories and insights collided. From there, we could begin to draw on what affected people the most and, therefore, what might also affect the viewer. What resulted were personal stories, moments and memories, anecdotes about teachers and mentoring, and insights about the individual bridges from technique to artistry.

Martha Graham: We all step out on the high wire of circumstance, and I have simply chosen not to fall. But for you (dramatic pause), what were some of your hardest decisions that had to be made?

MC:: I think the hardest part of this film was staying true to Juilliard and to the people past and present whom I came to love, and yet honor the drama and controversy that are important in a film. Juilliard was suprisingly very open to stepping out from under its veil of mystery, blowing the roof off the so-called ivory tower and being clear about some of the harder elements of their story. I think the difficulty for me is that I fell in love with so many things, and one of the wonderful and terrible parts of the filmmaking process is editing. Between interviews, verite footage, and archive material, we amassed more than 300 hours of material and over 4,000 still images. Originally, we made a fully cut four-hour version of this film. But it was clear to all of us that more is not always better. Susan is invaluable as the third eye who still sees after everyone else is blinded. We also had some wonderful past filmmakers from the AMERICAN MASTERS family come into some late screenings for objective criticism both cruel and kind, which really helped shape some major changes in those last weeks.

Pina Bausch: Do you characterize yourself as a “woman filmmaker” (pause, for cigarette exhale), and do you think gender effects the directorial process?

MC:: No, I don’t. I think that sometimes when women conduct interviews — as in life when they hold conversations — they are sometimes drawn to the personal or emotional. But ultimately I believe that films come out of the person, the individual, regardless of gender. And what makes you who you are, and thus the films you create, is the mystery of your own life, and the times in which you lived. It is the word that rhymes with “orange.”

Kevin Kline: There’s a great story about Stella Adler teaching an actor who was doing Hamlet in her class, and he had, you know, kind of brought it down to just a kind of conversational, very naturalistic place that he was very connected to. And she said to him, darling, Hamlet is not a guy like you. (laughs) I am wondering, did you find Juilliard to have that Hamlet-like quality, which its reputation suggests, that it floats somewhere above the rest of us.

MC:: I knew the Juilliard reputation, and yes, incredible, amazing things happen there and have happened there. But in the end it is people — people on individual quests and people with collective goals working to achieve something important and lasting in the arts. And not just for themselves but for the on-going preservation and appreciation of these art forms in this country and the world. And yes, they are a little more talented than other people. But I wouldn’t want any of them to have directed this film, or fixed my leaky sink — everyone has their area of expertise. But, as actor Bradley Whitford said in our interview, “It’s a little unnerving when you get on the elevator in the morning with some nine-year-old kid who you know is better at what he does than you will ever be in your life”

John Houseman: Having worked with Orson Welles, run MGM, starred in The Paper Chase — as well having been the first director of the Juilliard drama division — I have been in the midst of luminaries and am one myself. How did you juggle the egos of all the stars?

MC:: Interestingly, egos were set aside, but schedules were not. Because we had a limited budget we had to set interview days and plan over six months in advance in order to have over fifty people with staggering schedules come in one after another to our “interview set.” It was pretty amazing, and I take my hat off to Amy Schewel. In Los Angeles we had interview days that included Val Kilmer, Bradley Whitford, Eriq La Salle, Lisa Gay Hamilton, Bill Conti, and John Williams. In New York, I think in one day I began at 9 a.m. and interviewed the following people: Leontyne Price, James Levine, Kevin Kline, Leonard Slatkin, Dorothy DeLay, and Michael Kahn. I didn’t feel very well when it was over. But James Levine complimented my ruthless quest for the truth. And that has stayed with me for a long time, even though I think he was kidding.

Michael Kahn: If this film goes nowhere, do you think you will enjoy working at the perfume counter at Bloomingdales?

MC:: I think it will be hard, but like young Juilliard actors, who you so lovingly teach, it is not about a role, it is about a career. You have to be in it for the long haul, and if you don’t love it — get out.

Bill Conti: When I was a student at Juilliard, my teacher used to throw my music in the trash, page by page without even having looked at it. How did the process of making the film compare with writing the book?

MC:: The book was much harder than I initially thought it would be. The inspiration for having a companion volume was our first glimpse at the previously untapped Juilliard archives. When we realized how many incredible images had not been seen before — and after we realized the limitations of the film for the exclusion of all these images — we felt it was a natural extension. Amy Schewel and I were so excited to keep going with all that was in our minds that we couldn’t fit in the film. We wanted to give more time to areas we felt had been condensed (for good reason), such as composition, The Juilliard String quartet, and chamber music. We thought that one project would flow naturally into the other and that it would be easy to do the book. But, surprise, surprise, it was not. While all the ideas were in our head and we were not starting from scratch in terms of our knowledge of the school, it was a different medium and required a different way of thinking. But we love the book, and it has a beautiful use of color. When making the film, we never strayed outside of the Juilliard world, there are no outside opinions. Every interview is from a Juilliard graduate or faculty member, every piece of music heard is from the Juilliard archives, or a live performance. And the same is true of the book, all of the quotes in the text are drawn from the interviews conducted for the film. Amy and I filled in the blanks. It is a true companion to the documentary in that it complements, but it also goes to places that the film does not, and visa versa.

Thank you.