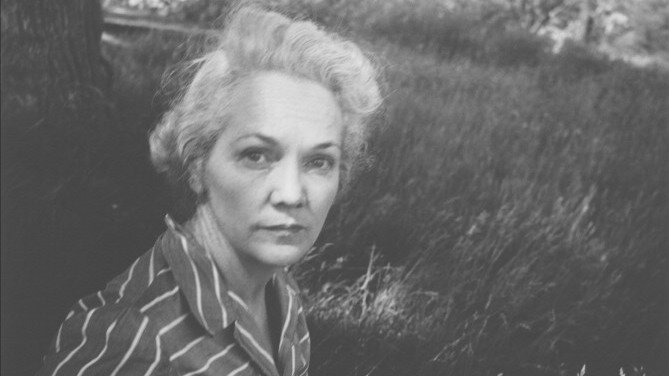

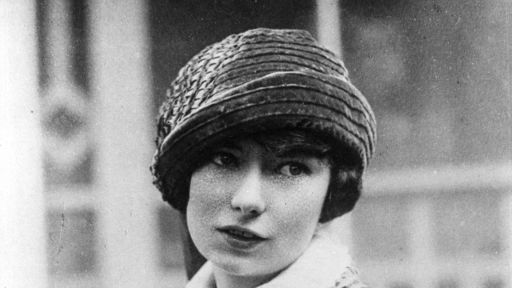

When Katherine Anne Porter left her home state of Texas for New York, she brought with her the hard edge of a Western pioneer. Passionate and intelligent, it was this edge more than anything that made her name as a writer. Despite her self-imposed exile from her home and Southern background, Porter used this distance as a means of coming to terms with the memories she sought to escape.

Born in India Creek, Texas in 1890, Katherine Anne Porter lost her mother at the age of two. Raised primarily by her paternal grandmother, Porter became strong and self-reliant at an early age. Both the loss of her mother and her father’s subsequent neglect had a lasting effect on Porter—making her incredibly attentive to the harsh realities of the human endeavor.

At age fifteen she married John Henry Koontz, the first of four husbands. Throughout her entire life she would continue to have passionate affairs marked by dramatic and vicious break-ups. She spent her early twenties moving from Texas to Chicago and back, working as an actress, a singer, and, later, a secretary. In 1917, after a battle with tuberculosis, Porter took a job as a society columnist for the Fort Worth CRITIC. Two years later she moved to Greenwich Village, where she began to work seriously as a fiction writer.

Supporting herself with journalism and “hack” writing, Porter published her first story in CENTURY magazine. Though CENTURY provided her with a good sum for the story, Porter was rarely to return to popular magazine publishing, choosing instead the freedom of little magazines. A perfectionist concerned with controlling every word of her stories, Porter gained a name for her flawless prose. Often concerned with the themes of justice, betrayal, and the unforgiving nature of the human race, Porter’s writings occupied the space where the personal and political meet.

In 1930 her first book, FLOWERING JUDAS, was published by Harcourt Brace. Though a masterly collection of short stories, it met with only modest sales. It was not until almost ten years later that she published her second book, a collection of three short novels, PALE HORSE, PALE RIDER. She followed this in 1944 with THE LEANING TOWER AND OTHER STORIES. Concerning herself overtly with the rise of Nazism, Porter was able to further investigate the dark side of the average person. It was not, however, until nearly twenty years later that she was able to address the topic in greater depth.

SHIP OF FOOLS (1962), was Porter’s first and only novel. Dealing with the lives of a group of various and international travelers, the book became an instant success. Based partially on a trip to Germany thirty years earlier, SHIP OF FOOLS, attacked the weakness of a society that could allow for the Second World War. After 1962, Porter did very little writing, though she won a Pulitzer Prize for her COLLECTED STORIES four years later.

In 1977, fifty years after her protest of the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, Porter wrote an account of the event entitled THE NEVER-ENDING WRONG. Three years later she died at the age of ninety. Outliving most of her contemporaries, the strong-willed Porter left behind a thin but insightful body of work. Her flawless pen and harsh criticism of not only her times, but of human society, made Porter a major voice in twentieth century American literature.