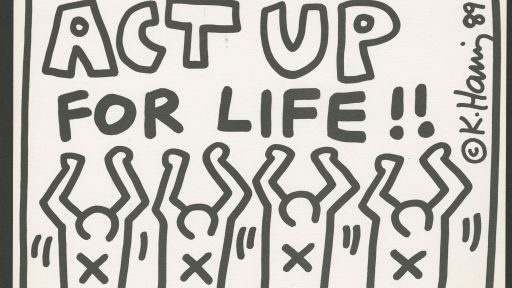

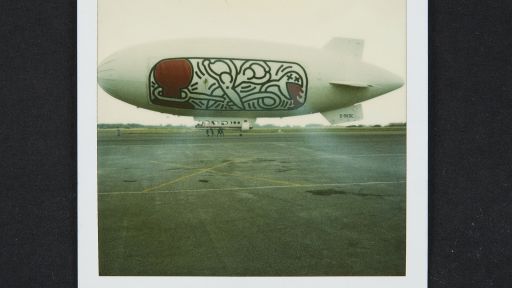

International art sensation Keith Haring blazed a trail through the legendary art scene of 1980s New York and revolutionized the worlds of pop culture and fine art. This fascinating and compelling film – told using previously unheard interviews that form the narrative of the documentary – is the definitive story of the artist in his own words. The film also includes exclusive, unprecedented access to the Haring Foundation’s archives, capturing the wild, creative energy behind some of the most recognizable art of the past fifty years. Following Keith Haring’s diagnosis with AIDS in 1989, he asked writer and art critic John Gruen to write his biography. For five days in the summer of 1989, Keith gave Gruen in intimate and candid detail the story of his life and these interviews are included in the film. Haring’s closest friends, family and collaborators – from the sleepy Pennsylvania of his youth to the mythic clubs of gay New York – share their revelatory encounters, touching poignantly on the AIDS crisis, which made a tragic icon of this life-affirming artist.

Keith Haring: Street Art Boy

Explore the definitive story of international art sensation Keith Haring who blazed a trail through the art scene of ‘80s New York and revolutionized the worlds of pop culture and fine art. The film features previously unheard interviews with Haring.

Features

Keith Haring: Street Art Boy is a production of BBC Studios Production for PBS and BBC with THIRTEEN Productions LLC. Filmed, directed and produced by Ben Anthony. Executive Producer Janet Lee. Producer Alice Rhodes. Michael Kantor is executive producer for American Masters.

About American Masters

Now in its 37th season on PBS, American Masters illuminates the lives and creative journeys of those who have left an indelible impression on our cultural landscape—through compelling, unvarnished stories. Setting the standard for documentary film profiles, the series has earned widespread critical acclaim: 28 Emmy Awards—including 10 for Outstanding Non-Fiction Series and five for Outstanding Non-Fiction Special—two News & Documentary Emmys, 14 Peabodys, three Grammys, two Producers Guild Awards, an Oscar, and many other honors. To further explore the lives and works of more than 250 masters past and present, the American Masters website offers full episodes, film outtakes, filmmaker interviews, the podcast American Masters: Creative Spark, educational resources, digital original series and more. The series is a production of The WNET Group.

American Masters is available for streaming concurrent with broadcast on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS App, available on iOS, Android, Roku streaming devices, Apple TV, Android TV, Amazon Fire TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. PBS station members can view many series, documentaries and specials via PBS Passport. For more information about PBS Passport, visit the PBS Passport FAQ website.

About The WNET Group

The WNET Group creates inspiring media content and meaningful experiences for diverse audiences nationwide. It is the community-supported home of New York’s THIRTEEN – America’s flagship PBS station – WLIW21, THIRTEEN PBSKids, WLIW World and Create; NJ PBS, New Jersey’s statewide public television network; Long Island’s only NPR station WLIW-FM; ALL ARTS, the arts and culture media provider; newsroom NJ Spotlight News; and FAST channel PBS Nature. Through these channels and streaming platforms, The WNET Group brings arts, culture, education, news, documentary, entertainment and DIY programming to more than five million viewers each month. The WNET Group’s award-winning productions include signature PBS series Nature, Great Performances, American Masters and Amanpour and Company and trusted local news programs MetroFocus and NJ Spotlight News with Briana Vannozzi. Inspiring curiosity and nurturing dreams, The WNET Group’s award-winning Kids’ Media and Education team produces the PBS KIDS series Cyberchase, interactive Mission US history games, and resources for families, teachers and caregivers. A leading nonprofit public media producer for more than 60 years, The WNET Group presents and distributes content that fosters lifelong learning, including multiplatform initiatives addressing poverty, jobs, economic opportunity, social justice, understanding and the environment. Through Passport, station members can stream new and archival programming anytime, anywhere. The WNET Group represents the best in public media. Join us.

Support for American Masters is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, AARP, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, Rosalind P. Walter Foundation, Cheryl and Philip Milstein Family, Judith and Burton Resnick, Seton J. Melvin, The Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation, The Ambrose Monell Foundation, Lillian Goldman Programming Endowment, Vital Projects Fund, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, Ellen and James S. Marcus, The André and Elizabeth Kertész Foundation, Koo and Patricia Yuen, Thea Petschek Iervolino Foundation, The Marc Haas Foundation and public television viewers.

♪♪ ♪ ♪ -He kind of took New York by storm, and he was in all the magazines before he was 25, worldwide.

-My philosophy was always that art really could communicate to larger numbers of people instead of that elitist group of people that could afford it and "understand it."

-90% or more of the people using the subways would never go to the Museum of Modern Art.

-That was around the time when Keith kind of went "Bing!

I'm going to do this."

-The crawling baby, the dog, flying pyramids, dancing man, turning them into his, like, own vocabulary.

-I was realizing the potential of images and how much power they had to speak almost as a language.

-Keith had an inherent need to have a dialogue with people.

-For me, the market has very little to do with what art is supposed to be.

-I was formally introduced to this painting here yesterday when the brother painted it.

We love it.

He alright with us.

-The traditional art world didn't get that he felt that art should be as accessible as possible.

-As sort of a romantic idea of being an artist of the people, I just found a way to do it that was very direct.

-He was so prolific.

I would come back the next day, and there would be like 4 new paintings and 20 drawings.

Okay.

-I think it's more important to keep coming up with new images and things that were never made before, live as fully and as completely as you can, and deal with the future as it comes to you.

-He was celebrating life up to the very end.

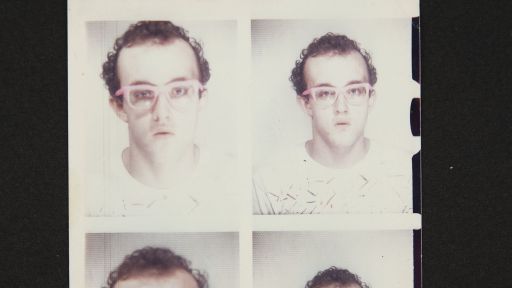

♪♪ ♪♪ -So this is the eighth day of August, 1989, and I'm speaking with Keith Haring.

One of the things I want to ask you is what kind of a little boy you were, if you recall.

-I had glasses from the time I was in second grade.

I was already sort of a little nerd.

I mean, I think I was real insecure about being last to be picked for teams.

My mother was really trying to sort of mold me into something, I suppose.

I mean, the pressure to play Little League or to go play ball.

I mean, I was really more interested in doing silly creative things like inventing a club or arranging some sort of club house.

-And you were the eldest of how many?

-Of four.

Yeah, after me, they had a girl, and then after two years had another girl, and my third sister was born when I was 12 years old.

-Kutztown is a small town, what I would call a very conservative town in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country.

I call it sleepy because... Well, just because there's not much going on.

And that definitely was Keith's opinion of it.

We don't have an exact date on this.

-But we're pretty sure it's third grade.

-"When I grow up, I would like to be an artist in France.

The reason is because I like to draw.

I would get my money from the pictures I would sell.

I hope I will be one.

Keith Haring."

I mean, he was always drawing -- drawing in school when he wasn't supposed to be.

-He would draw on any kind of paper -- backs of store lists, backs of cards.

Yeah, he was always open to drawing anything.

-And he found a friend in Kermit.

They both liked to draw.

-We grew up in the same town two blocks away from each other.

A real friendship started, I think, you know, in grade school, and pretty much that's when we started making things together.

We delivered newspapers on the same street.

We were reading the paper day by day.

There was a lot of crappy stuff going on.

We were talking about it, and it bothered us.

-We will prevail in Vietnam over the communist aggression.

Keith, as long as I knew him, was an activist.

When Nixon ran for president, we found ourselves running around town with bars of soap, putting stuff about Nixon on buildings.

In Kutztown, people didn't write on things that didn't belong to them.

You know, rolling hills and cornfields and horse and buggies and absolutely no graffiti.

♪♪ Keith got interested in that whole Jesus Movement.

What it illustrated to me was a kind of a longing to be a part of something.

-I guess it was around that time I discovered smoking pot for the first time.

♪♪ ♪♪ -What do you make of that one, Allen?

-Smoking pot.

We were pretty well convinced he was doing that.

-By this time, I was doing really stupid drugs -- angel dust with my friend who was making it.

♪♪ But then I got a job in the arts and crafts center in Pittsburgh.

Even though I wasn't a student, I proceeded to use the other facilities around there to do my own work.

One of the most important things in Pittsburgh was the Carnegie did the Pierre Alechinsky retrospective, who I had never heard of before.

And the work was so close to what I was doing.

It was the first time that I felt that I was doing something that was worth something.

At 20 years old in 1978, I was having my first show on my own.

I knew that I had to make the break.

I knew I had to go to New York because that was the only place where obviously I was going to find the intensity that I wanted to find, both in terms of the art world and in terms of my life.

Also, I was realizing little by little that I had to sleep with men.

I had looked into schools and found this school which seemed incredibly interesting to me, which was School of Visual Arts.

-It worried us that he would be exposed to things that we try to protect children from.

And we would have no control over that.

New York of the late '70s, when I arrived, when Keith arrived, It was a place a lot of people were afraid to go to.

It was downtrodden.

-In 1978, it was bankrupt.

-Good evening.

New York City was on the brink of default for most of the day.

-A lot of the buildings were abandoned.

It was extremely dangerous.

There was a lot of crime.

♪♪ But there was a great punk rock music scene and an underground film scene.

And it was the place to be.

♪♪ -Tribute to Gloria Vanderbilt, take one.

-I was in school full-time with a purpose in this new environment and was just working.

It was all new to me, and it was all very exciting.

-And you were 20.

-And I was 20, yeah.

I sort of met some people very quickly.

Like in my drawing class, I immediately gravitated to this one girl who was named Samantha McEwan.

-And he literally sat down, I mean, opposite me but our knees touching and he just went, "Can I draw you?"

And that was Keith.

-♪ It's the middle of the month, it's happening all over town ♪ ♪ You know it's got me reeling forward ♪ ♪ Got me falling to the ground ♪ -I was in the hallway, and I heard Devo music, and there's Keith painting himself into a corner with these black strokes.

And every stroke was to every beat of the music.

And he had painted the entire room and he was at the very end and he was standing in the corner and he was marking his mark and I was like, "Wow."

I said, "This is the reason why I came to New York."

-I think Keith kind of, like, ruled that school from the time he got there.

-He lived in a tiny apartment on the third or fourth floor.

Huge roaches and plywood floors.

Keith's room was virtually a closet, but it had, like, a phonograph.

And he ended up playing, like, "Rock Lobster" like 20 hours in a row while he would be drawing in the apartment.

-♪ We were at a party ♪ ♪ His ear lobe fell in the deep ♪ ♪ Someone reached in and grabbed it ♪ ♪ It was a rock lobster ♪ -No one in the East Village had a television set.

We went out every night.

That was our entertainment.

-At nighttime, I'm becoming part of nightclub scene and then begin to become part of this scene at Club 57, a Polish church.

In the basement of the church, there was a social hall.

-♪ I want to see you tonight ♪ -We were really kind of bored with the art world as an elitist place.

It seemed like it was trying harder and harder to be more and more esoteric and not want to include the public at large.

-Club 57 was our way of going to Hollywood without having to go to Hollywood.

That whole spirit of DIY, we're not going to be uptown groveling at the feet of corporate entities for their approval to do anything.

We can find another playground.

♪♪ -♪ Want to make love to you under the strobe lights ♪ ♪ Want to make love to you under the strobe lights ♪ ♪ Strobe lights, oh ♪ -What I'm obsessed with at this time is trying to figure out why I'm an artist and if I'm an artist, why I'm an artist, and also becoming aware of and very interested in what's happening on the streets of New York.

I'm fascinated by the graffiti that I was seeing.

Not only big things on the outside of cars, but the incredible calligraphy which was covering the insides of cars.

♪♪ -It was to compete with advertising in a certain regard.

Like, all these companies were just forcing their products in your face all the time.

It's like we want to force ourselves in people's faces.

-I started to notice him in my neighborhood in the Lower East Side was he started to come down to get more acquainted with graffiti writers.

-I felt immediately an affinity to the work as if I had known it a long time.

This incredible pop cartoon sensibility from kids that had grown up watching cartoons with Technicolor.

The forms seemed very similar in a way to the kind of drawings that I was doing, even though I wasn't making letters.

They had the same kind of volumous, aggressively fluid lines, which were obviously done really directly with very little hesitation but just really, really strong.

From the time I was a kid, I had this tremendous guilt about all the things that white people had done, you know, from [bleep] over the Indians to the whole civil rights movement.

And I felt a much closer affinity to culture and people of color than I did to white culture in a way.

-Disenfranchisee youth creating really beautiful, urgent messages of, like, self identity.

Way before Instagram.

You know, I like to call it Instadamn, because Instadamn was like, "Damn, look at that."

♪♪ -The famed Times Square Show organized by Collaborative Projects was the first time that the art world acknowledged that this underground existed.

-The art world is very unpenetrable at that time.

The velvet ropes are there, and you don't want just anyone crashing those velvet robes.

-The Times Square extravaganza on 41st Street.

-There was starting to be this whole movement in New York of people trying to do things outside of the regular gallery system.

-Lee Quiñones and I did a painting on the front of the building, a Fab 5 piece which we spray-painted.

Keith was a big fan of graffiti.

He was watching trains, looking at tags, and things like that.

He had good questions, I had some answers, and we just became fast friends right away.

-It was really a moment where the uptown culture of graffiti and rap kind of collided with the punk New Wave aesthetic.

So that was around the time when Keith kind of went "Bing!

I'm going to do this."

-A few days or a few weeks right after the Times Square Show, I just started doing these new flying saucers... and these animal figures which sort of looked like they could have been cows or sheep or something, but they had very sort of square noses.

They're really roughly, roughly, roughly drawn because I hadn't done anything figurative in a really long time.

And out of these were sort of really born the entire vocabulary that came afterward.

And all of a sudden, it just totally dawned on me, like, "What am I doing in school?"

I had discovered my own work.

So I decided I was going to have a show.

-The solo show in New York City at P.S.

122 -- I went over there, and I think Keith was there on his own, and it was absolutely spellbinding.

I mean, it was really -- you know, chills went down your spine.

-I had been given the space only for, I think, a one-month period.

-It became a buzz and everybody wanted to go and see what was there, you know?

Everybody wanted to go see it.

-And I think that was around the time when Keith brought Tony to see this work.

-How's that?

-Too tight.

I can't turn.

-I'll move around more.

-Move here.

Yeah, there's nothing.

-You know, Tony is a very forceful personality.

-I've done shows with Picasso, Bacon, everybody, and I'm like, "They're like a dead, dead rat."

I know my crap.

Please.

I know the editors of Vogue.

I know every [bleep] photographer in the world.

-This is the guy that literally went into the Museum of Modern Art with a spray-paint can and painted "Kill lies all" on the most famous Picasso in the world.

-Why did you mark up that painting like that?

-To tell the truth.

-To tell the truth?

What does that mean?

-That means to kill all the myths.

The myths of art.

To tell the truth.

-Everyone's like, "Oh, he's the guy.

He's the guy who defaced 'Guernica,' and he's an art dealer?"

-I would go to the Museum of Art just primarily to look at "Guernica."

However, the fact that he believed in protest against war and was committed enough to stand up to what he knew would be incredible attacks from the art world, I respected that.

-We went to see the Keith Haring show, and the animated line was so original and so active that it immediately caught your attention.

It didn't look school-trained.

It didn't look qualified.

So I grabbed that.

-The other thing that was happening was that I had started to draw graffiti for the first time on the streets with marker.

And I started drawing the animal, which more and more looked like a dog and kept getting referred to as a dog, and the person crawling on all fours, which then the more I drew it and the more and the proportion of the head got bigger, the more it got referred to as the baby.

-Amongst the graffiti community, placement was a significant thing, and he would place them in unique places.

And there was this little crawling baby.

And I was like, "Yo, that's dope.

That's dope."

-One day I enter the subway and see an empty black panel, which has been put there to cover an old advertisement.

Immediately, I knew that I had to draw on top of this panel.

I mean, it was like a waiting, perfect surface.

I knew that I had to go aboveground and buy chalk.

-Keith was not sure about using spray-paint.

He is very sensitive being white.

He didn't want to be this white guy coming into a graffiti space that was largely people of color.

He wanted to be a part of it, but in his own unique way.

-The deficit in the city and the lack of advertisements maybe at that time made for a lot of vacancies on those blackboards.

-After the first one, I started seeing them everywhere.

And within days, I knew what I had discovered here.

I could go back down in the subway, you know, a week later and the drawing would still be there.

Within a week, people would come up to me.

"I saw this other drawing.

I saw the drawing.

You're the guy that did the drawing."

Blah, blah, blah.

-He would do over 100 sometimes in one day.

It would be enormously exhausting to take the train, jump out and do one, another one, another one, another one, go to next station, all the way to Harlem, all the way back.

I mean, you'd just be dead.

-You had to create a lot of work to be seen in a sea of 10,000 subway trains.

Where the train goes by [Imitates trains] and you're like, "Wow, what was that?"

And it's a blur of color.

But here you got the opportunity to have an arrested audience.

And they're like, "This is a phenomenon.

What's going on?"

-For everybody, I guess.

I mean, I don't get paid to do it.

But I do it down here so lots of people can see it.

-Keith had an inherent need to have a dialogue with people.

And he knew what he was doing, for crying out loud.

He was sending a photographer around to every place he did the drawing to photograph every drawing.

♪♪ -All of a sudden in Times Square on the main luminescent display, there was Keith, animation of his figures now on the middle of Times Square.

♪♪ -What did you guys think when you saw that?

-We go, "Yay!"

It was great, yeah.

-Apart from anything else, I think it was one thing that he felt his parents would definitely appreciate.

You know, that is impressive.

-I moved in with Samantha, who was Kenny's girlfriend.

But we've become really good friends by this point.

She has found an apartment on Broome Street.

At this point, I'd meet Juan Dubose at St. Marks Baths, have great sex, and just decide that this is the right person to me.

He's black.

He's really thin.

He's the same size as me.

We decide that he should move in.

And we buy a tent because Samantha has got to walk through our room to get to the bathroom.

So we had this huge indoor tent so that we have privacy.

And also what is starting to happen for the first time, people are starting to be interested in buying the work.

They come to the apartment and start to buy things.

This man from London comes to the studio and buys a group of about 10 drawings.

I mean, it's the first time that I've got over $1,000 in my hand and for the first time in my life realizing that I can live off of being an artist.

-I was sitting at the kitchen table when he came in.

I don't know if I was having lunch or what.

And all of a sudden he reached in his pocket and he took out some $100 bills and laid them on the table.

And I said, "What's that?"

He said, "Mom, I'm making money on my art."

And I said, "Well, don't you need it?

I know it's expensive to live in the city, and you need to buy things and you need supplies."

He said, "I'm doing pretty good, Mom, and I want to start repaying you for all you've given me over the years."

That's when I realized that some of the people do like his art.

-I was starting to have dealers sort of fight over me.

Collectors are asking to come to the appointment, and then they want to haggle over prices or they're people that you don't even want to talk to them to begin with because they're sort of creepier and creepier.

Already, they're trying to rip me off for whatever they can.

-At that time, I really told him, "Keith, I mean, think of doing something that would last.

You know, maybe paintings or something."

"Oh, no, I'm not going to be an old-fashioned painter.

It's not about that."

I said, "You go and find a way that could be new."

-I think it's more important to make a lot of different things and keep coming up with new images and things that were never made before than to do one thing and do it well.

They come out fast, but it's a fast world.

-When he had a show, we went, and... -There weren't many there that were dressed like us or that were as quiet as us or didn't understand what was going on.

-We were definitely the oldest there, probably.

-Yeah.

-We weren't there too long.

-No.

-There was every type of person.

People who would never go to an art gallery opening, they were there.

-We got homeys from the streets, Lower East Side, black and Puerto Rican people partying.

You know, it was a different world.

So when those white folks that just went to the regular art world things would show up, they'd be, like, blown away.

-I can't get over it.

-I'm from the South.

I'm a Southern painter.

Marvelous.

-Thank you.

-Haring has become a hot property.

They ooh and they ahh.

-Downstairs is unbelievable.

I want to buy a few of these little wooden things.

-And they pay plenty.

Within the first few days of the show, about $250,000 worth of his pieces sold.

Not bad for a 24-year-old kid from Kutztown.

-Literally, it was packed.

No one had ever seen an art opening in the established art world like this.

All of a sudden we were like, "Oh, we're big boys now.

We're, like, in the big boys world."

And we started making big boy paintings.

♪♪ -When the great Wall Street bull market began in 1982, it was one of the markers of New York being different, of New York having a kind of manic self-confidence.

♪♪ -Just a sense of it's okay to make money.

In fact, it's okay to mainly think about making money.

-There was a generation in art world, first of all, that was supposed to be aloof from all those things that suddenly young folks are diving in head first, awash in dollars.

There was a big party going on, and it was studded with famous people and the want-to-be-famous.

And then bonafide stars like Keith.

-There are starting to be offers for exhibitions all over the world.

-[ Speaking Japanese ] -The demand for the work and the way that I was working and the whole sort of graffiti performance aspect made it possible for this whirlwind tour now of going from place to place.

-Haring got plenty of publicity, and West German television pictures of him working were seen in East Germany.

-Keith was an amazing person to watch paint.

I did it many times.

-People were very charmed by him because he was such a young spirit and he was so American.

He really represented something.

You know, this youthful spirit and energy in the sneakers and the jeans and being gay and hanging out and going to clubs.

-[ Speaking German ] -He really was treated like he was a rock star.

-♪ Shoot me with your love ♪ ♪♪ -Sometime right in this time, I begin for the first time to go to Paradise Garage.

I may have never been the same since.

♪♪ -At that point, we were going to the Paradise Garage, which was a big gay disco on the West Side with the greatest sound system ever known to man.

-It was so hot inside just from dancing that people were, you know, only when shorts and little outfits and things and sweating, and the music was phenomenal.

-We went every Saturday.

And there was no alcohol served at this club, so everyone was on drugs.

It was 3,000 black people on drugs with Keith and I.

-Many people are on hallucinogenic drugs.

It's sort of a communal, elevated spiritual experience.

-We smoked pot like cigarets.

And that's not counting the mescaline and the acid and the psilocybin mushrooms and the part that they never play up enough in, like, the Keith Haring story is the drugs.

I always think that a lot of Keith's vibrations around everything that he drew was kind of psychedelic.

-On the corner of Houston Street and the Bowery, where many derelicts and bums hang out, I walked past this wall almost every day on my way to go to the studio.

-I wasn't proclaiming it, but people were saying the amber walls all belong to Lee in New York.

So he out of respect and out of the generosity and out of the just the sweetness that he had as a person asked me, "Lee, can I have permission to paint that wall?"

I was like, "Keith, I don't want to paint it because it has a crack in it."

-I do this mural in two days or something, do this amazing, incredible wall.

I mean, it's glowing.

The fluorescent paint is so bright and the sun hits this wall, and it's just this incredible sort of monolith standing on the thing.

-It was outrageous how powerful it was.

-I was formally introduced to this painting here yesterday when the brother painted it.

We love it.

He alright with us.

But we don't drink that wine and wash some windows and keep right on painting.

Keep it up and don't erupt.

Don't stop the chocolate crew and the gang.

-From painting vacant ad spaces in subways to being flown around the world is quite a leap.

-I went to Australia to do several projects.

The National Gallery of Victoria was a huge building with a glass front on it.

I was going to do a painting on this wall.

It turned into this major controversy and even being on the front page because people there were seeing it as Aboriginal.

But I was doing what I had been doing in New York and in America and all over the world.

It just coincidentally was the same kind of line drawing as Aboriginals.

Well, the final result was that about a month after I had left, the center panel ended up getting a shot put through it.

And so the whole thing had to be removed.

In London, I painted Bill T. Jones, and painting him, every inch of his body from head to toe to the tip of his foreskin, and then photographed him and all these sort of poses.

-I never felt exploited by Keith.

What was an article in Rolling Stone magazine talking about his Bwana syndrome.

Who is this white guy surrounded by all these brown people?

♪♪ -At this point, I've made a sufficient amount of money, which I have a sufficient amount of guilt about and want to sort of share with my friends.

For my birthday, I do my very first party of life.

-May 16th.

Paradise Garage, 1984.

And this is one of those handkerchiefs like the gay boys liked to wear in their back pockets.

Keith's parties were so exuberant.

People were young, healthy, alive.

Fantastic bodies.

It was like something you might imagine, you know, the ancient ritual where they've already pulled the heart out of the slaves and then now the sun has come up and it's coming through Stonehenge just perfectly.

And now we're gonna celebrate.

It was very pagan, and Keith just embodied that.

-We were inviting just really gorgeous people to this party.

You know, from street kids to Calvin Klein.

Anyone who was anyone at that time in New York had found a way to get an invitation to this party.

Diana Ross showed up, which for the Garage was the ultimate highlight.

And I had just painted a jacket for Madonna, and I've asked her if she'll sing there.

And she agrees that she'll sing there.

They didn't take to Madonna.

It's like, "Who is this trashy white girl that can't sing?"

-And we said, "Oh, you know, she doesn't have a great voice."

But then he said, "Andy says she's gonna be the biggest thing."

And we said, "Oh, sure, sure."

Well, Andy was right.

-He got well known, and then he got around Andy.

And then everyone started having one name that was around Keith.

It was, you know, Brooke and Andy and Grace, Yoko and Michael.

Having his stuff taken seriously by the art world was one thing, but getting to hobnob with everybody on Hollywood Squares was like a whole nother level of fame that he really relished.

-All of a sudden, he went from being this kid from Kutztown to hanging out with Farrah Fawcett.

-Juan was my lover during this time, but I was having more opportunity, and especially with more traveling, more notoriety, and more boys around me all the time, I was already starting to become less and less true to Juan, really, and it was hard because I was constantly surrounded by temptation.

-There are some people who felt that, you know, once he got famous, he abandoned them.

There was something about Andy's sense of art as a business that really appealed to Keith and which, you know -- that philosophy did play a role in Keith's decision to open the Pop Shop.

-They call it the Pop Shop.

From T-shirts to posters, pins and pendants to watches, it's the place to pick up, well, just about anything from pop-art sensation Keith Haring.

-So the Pop Shop was a reaction to "You can only have my work if you have thousands of dollars."

It was "You can buy a T-shirt and be part of what I'm doing."

-I knew that I was going to get a lot of criticism for it, but I also knew that it was the thing the work was calling for and that it had to become.

-It never made lots of money.

Never made money.

-What was the point of it, then?

-It was everybody could have art.

Everybody could be enjoying something.

-But what happened was Keith was accused of selling out.

-Do you think the Pop Shop will in any way interfere with Keith Haring, the artist?

-I mean, to me, it's all one and the same thing.

I mean, to me, the Pop Shop is part of Keith Haring, the artist.

-He was not somebody who said, "Oh, never mind, I'm not going to read those reviews.

They don't matter."

He read everything and, you know, it upset him.

-Things had seriously changed already in New York because of this new horror of AIDS.

And little by little, it's building up in the news.

Calling this thing, like, gay cancer.

And people around me started to get sick.

The first person that I knew that died of AIDS was Klaus Nomi, who had been around from Club 57 days.

-You would be with your friend, a vivacious, cherubic, 20 year old.

And then you would not see them for a couple weeks and you run into them in the street and it would be like, "What the [bleep]?"

You know, all of a sudden, they looked like a skeleton.

And it would happen that fast.

-At that point, if you got a bruise, you thought you had K.S.

You thought you were going to die as a gay man.

And then there was the stigma and the shame.

It was so shameful, AIDS, at that point.

-There were doctors who were so frightened that they wouldn't even let patients in their office.

They just would send them down to my office to see them.

-We got very myopic about creating, doing things and doing things and doing things I think in a lot of ways to avoid the trauma of seeing friends die right and left.

-He said yes to everything.

-I painted Grace Jones for two live performances.

And I went to Marseilles in France to paint a backdrop for a Roland Petit ballet.

Did some graphics for some heart pills in Germany.

Designed four watches for Swatch.

Every trip coordinated exactly to leave after a Saturday night at Paradise Garage so that I don't miss any of my Garage time.

Don't let your brush sit inside the cup 'cause it can get knocked over.

I'm approached by this group called CityKids.

We come up with this brainstorm of an idea of making a banner and letting kids come and paint their own things inside of my lines.

After the three-day period, about 1,000 high-school kids had come to this thing.

It was this big, major event.

-The buses just kept unloading, coming from all five boroughs in New York City, bringing kids from everywhere.

I had never really been out of Brooklyn.

I didn't know people from Queens.

I didn't know people from the Bronx.

When you come from poverty, sometimes you think that that's all there is.

Every single person that you see represented on this banner had a voice.

But somebody feeling like your statement was important at 16, that changed everything.

-There was this thing that children were comfortable with me, and I was comfortable with them.

If you're not sure, you come to me and ask me, "Should they be painting with red or green here?"

I knew that they can sort of sense honesty in the drawing.

-"Without her, there'd be no me, no you, no liberty.

Keyon."

That was my statement.

1986.

I told you I couldn't draw.

[ Laughs ] We got to see life different.

And it gave you the opportunity to go, "Hey, there's more to life than just my everyday.

Let's see what else is out here.

Let's see what else we can do."

I got invited by Keith Haring to go up.

He was doing a mural in Harlem.

So now it's this world-famous -- The "Crack is wack" mural, right?

It was a nice, like, sunny summer afternoon day.

All I can remember is, "This is taking forever.

I think this is wack."

-It's a sight you can't miss.

If you live in the neighborhood or you pass 128th Street on the FDR Drive, you may have even wondered who did that and why.

Graffiti artist Keith Haring did it.

-'86 was sort of the beginning of the crack scene sort of starting in New York.

The whole thing was that it was quickly addictive.

It's a really terrible addiction.

It's much different than heroin addiction.

-Did you try it?

-Yeah, I've tried everything.

-When he would have been 27, Keith was showing regularly in galleries all over the world, and he had his first solo museum show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bordeaux.

And that show then would go on to the Stedelijk in Amsterdam.

I mean, these were major, major, major museums.

-I still haven't had an exhibition in a museum in the United States of any kind of substance.

-Keith sort of started to develop a Bosch-like world.

Really kind of intense and heavy.

We were like, "What the [bleep] is wrong with these American curators?

How come they don't get it," you know?

He was combated by critics for having a style that resembled illustration.

You could say, "Yeah, but think about what he was illustrating."

You know, all their belief systems were being challenged.

-It upset him that people just didn't get it.

They didn't get that he thought art was for everybody.

They didn't get that he felt that art should be as accessible as possible.

-During the summer, I started to notice trouble with my breathing.

Was inspecting every day and waiting to see the purple splotch.

And I found a spot on my leg.

So I went to a doctor and found out that it was, in fact, K.S., meaning that now I fit exactly the classifications of actually having AIDS.

Now it was gonna happen to me, and now I had to deal with it.

-Well, he had no delusions that he was gonna be cured or that the disease was going to change or anything.

He knew it was progressive.

He knew he was dying.

-You know, it's like you have to go on.

You, like, get yourself together, and you realize that this is not the end right there and that there's other things.

And you've got to continue and you've got to figure out how you're going to deal with it and confront it and face it.

I haven't heard from Juan Dubose for a long time.

His mother calls me and tells me that he died.

Telling people that Juan died is in a way telling people that I'm going to die.

-It was very sad.

There was an open casket, but Keith is looking at it and saying, "Well, I'm next.

Soon to be me there," you know.

He loved classical music in the end of his life.

He listened to that all the time very loud.

-Once Keith got his diagnosis, he basically just ramped up everything.

He just worked and worked and worked and worked and worked.

He created so much art.

♪♪ -[ Singing operatically ] ♪♪ -He traveled like crazy.

♪♪ -You know, once he got the diagnosis, he pretty much put himself out there.

He used his art to create attention and awareness.

-[ Chanting ] Racist, sexist, anti-gay, go away.

Racist, sexist, anti-gay, go away.

-If you don't have money in this city, you can't -- you know, it's an expensive disease.

People that can't get money to get treatment here, to get whatever you have, people just give up.

-[ Chanting ] Racist, sexist, anti-gay, go away.

-We always struggled raising money and rarely had more than $10,000 in the bank.

And he would come up and he'd say, "Peter, I really want to help with this action financially.

Could you stop by my studio?

I kind of have a cash business these days."

And I'd walk from my East Village apartment down to Soho.

He'd go off to his little knapsack thing that he'd have in the corner and he'd come back to me and hand me this huge wad of cash.

-And I have always been an incredibly energetic person.

And the hardest thing for me is to slow down that process.

Yeah, I believe that you live while you're living and you live as fully and as completely as you can.

And you deal with a future as it comes to you and as it's doled out to you.

-You know, he's certainly had some days that were very, very dark.

And certainly, you know, if you look at the work that he created in those last couple of years, there is a great deal of darkness in them.

-It became the hell and horror of it all.

Like some of the last paintings he did were really, like, all the beauty is destroyed.

All the happiness of it all is gone.

And now it's just a -- it's kind of like hell.

-Fan mail starting to pour in from this Rolling Stone article in which I have bared my entire life story.

At this point, I hadn't even told my parents that I was sick yet.

-There was hysteria and fear.

So many people had it, yet nobody was coming out and talking about it, especially nobody famous.

It was very brave of him to do that.

-♪ Dance ♪ ♪ Come on ♪ ♪ Yeah ♪ -Even in the state he was, he was celebrating life up to the very end.

-♪ Come on, come on, yeah ♪ -In fact, he was celebrating it a bit too much.

Like I would say, "Keith, I would rather think it's a good idea if you've maybe ate healthy, had some of this carrot juice, instead of doing a line of coke," and he'd be like, "[bleep] that.

"No, I'm just going to do this with the candle burning at both ends, bright, and not wait for anything."

-♪ Come on, come on, come on ♪ ♪ Unh ♪ ♪ Whoo ♪ -You know, I never had any sort of delusions about living until I was going to be an old person, but there's works that I created that are going to stay here forever.

There's thousands of real people, not just museums and curators, that have been affected and inspired and taught by the work that I've done.

So the work is going to live on long past when I'm going to be here.

[ Cheers and applause ] -Keith in January of 1990 attended the inauguration of Mayor Dinkins in New York City.

And the inauguration was held outside.

And he contracted a very, very difficult chest cold.

-It was just like Keith was the Eveready Bunny, and then the Eveready battery just died.

This is the last drawing by Keith.

He struggled so bad.

He really wanted to show that he could still do it.

And it was really hard for everyone.

-The nurse woke my parents to tell them that.

It was in the middle of the night.

They said his kidneys are failing, and that means there's not much time.

And my parents got into bed with him and held him for hours until he died.

-These are some of Keith's designs.

There you can see the baby.

-They're a little bit flashy and on the loud side, so I don't wear them much.

I'm not a flashy, loud guy.

-There was times when he drew in the pictures.

He did not sign his name, but he would draw a baby in the lower right-hand corner.

He always said that the baby was a symbol of life.

♪♪ -So we move to the Keith Haring, and we start the bidding here at $3.2 million, $3.5 million, $3.8 million already.

$3.8 million.

-♪ Watch out, y'all ♪ ♪ Here comes the boogie ♪ -$4 million.

$4 million.

Looking for $4.2 million.

$4.5 million.

$4.7 million I'll take for the Haring.

♪♪ -♪ Never thought I'd ♪ ♪ Find the special one ♪ ♪ Now you're here ♪ -At $4,700,000 for the Haring.

All done.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪