American Masters Explores the Cultural Legacy and Complicated History of Author Laura Ingalls Wilder in a New Documentary

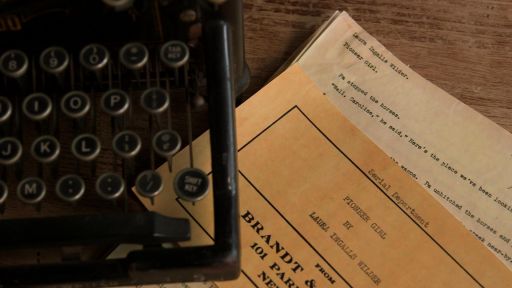

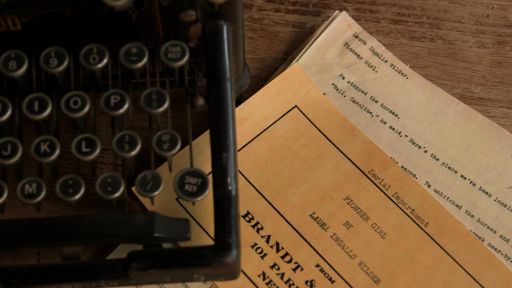

Laura Ingalls Wilder: Prairie to Page presents an unvarnished look at the unlikely author whose autobiographical fiction helped shape American ideas of the frontier and self-reliance. A Midwestern farm woman who published her first novel at age 65, Laura Ingalls Wilder transformed her frontier childhood into the best-selling “Little House” series. The documentary delves into the legacy of the iconic pioneer as well as the way she transformed her early life into enduring legend, a process that involved a little-known collaboration with her daughter Rose. Directed and produced by Emmy® Award winner Mary McDonagh Murphy (Harper Lee: American Masters).

Featuring never-before-published letters, photographs and family artifacts, the film explores the context in which Wilder lived and wrote, as well as the true nature of her personality. Victor Garber (Argo, Alias, “Titanic”) narrates, with Academy Award nominee Tess Harper (“No Country for Old Men,” Breaking Bad, “Crimes of the Heart”) reading Laura Ingalls Wilder and Amy Brenneman (NYPD Blue, Judging Amy, The Leftovers) reading Rose Wilder Lane. The film includes original interviews with Caroline Fraser, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her Wilder biography; Pamela Smith Hill, author of “Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Writer’s Life” and editor of Wilder’s New York Times bestselling memoir; Wilder biographer and editor of “The Selected Letters of Laura Ingalls Wilder” William Anderson; Christine Woodside, writer of “Libertarians on the Prairie”; authors such as Louise Erdrich, Roxane Gay, Lizzie Skurnick and Linda Sue Park; and actors from the beloved TV series Little House on the Prairie, including Melissa Gilbert (Laura Ingalls Wilder), Alison Arngrim (Nellie Oleson) and Dean Butler (Almanzo Wilder). Historians, scholars and fans provide additional perspectives on Wilder’s life and legacy.

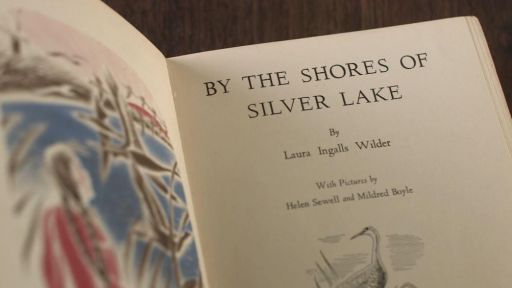

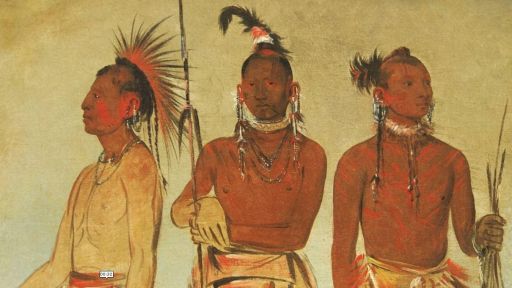

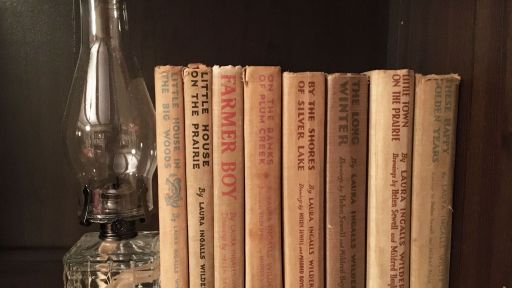

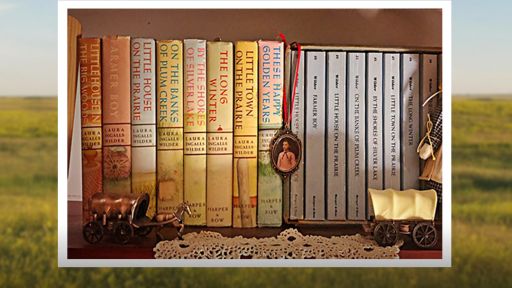

Wilder has an enduring fanbase — including self-proclaimed Bonnetheads — and the books and TV program loosely based on them have become cultural touchstones. Starting with “Little House in the Big Woods” (1932), the books chronicle the adventures of a family struggling to survive on the American frontier and have inspired four generations with the courage and determination of their heroine. Though Wilder’s stories emphasized real life and celebrated stoicism, she omitted the grimmer and contradictory details of her personal history: grinding poverty, government assistance, deprivation and the death of her infant son. In recent years, Wilder’s racist depictions of American Indians and Black people have stirred controversy, and made her less appealing to some readers, teachers and librarians. Laura Ingalls Wilder: Prairie to Page reveals the truth behind the bestsellers, exploring a rags to riches story that has been embraced by millions of people worldwide.

Now in its 34th season on PBS, American Masters illuminates the lives and creative journeys of our nation’s most enduring artistic giants — those who have left an indelible impression on our cultural landscape. Setting the standard for documentary film profiles, the series has earned widespread critical acclaim and 28 Emmy Awards — including 10 for Outstanding Non-Fiction Series and five for Outstanding Non-Fiction Special — 14 Peabodys, an Oscar, three Grammys, two Producers Guild Awards and many other honors. To further explore the lives and works of more than 200 masters past and present, the American Masters website offers streaming video of select films, outtakes, filmmaker interviews, the American Masters Podcast, educational resources and more. The series is a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET.