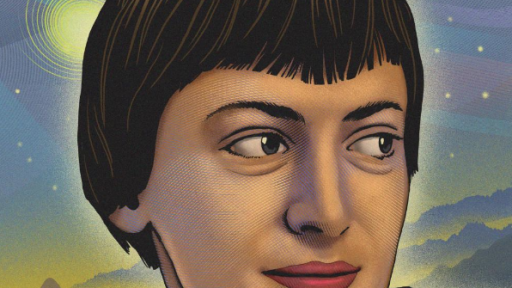

In 1969, Ursula K. Le Guin published a groundbreaking novel called “The Left Hand of Darkness” that questioned binary concepts of gender. Learn about the backlash from fans that found the book too controversial as well as criticism from feminists who felt that she didn’t go far enough.

Features

♪♪♪ Le Guin: I wrote a book, back in the '60s, called 'Left Hand of Darkness.'

What I was first asking myself, you know, 'Well, okay, what [laughing] is the difference between men and women?'

And the means I used to talk about it was to invent a race of people who are androgynous, fully androgynous.

You only become sexually active once a month and you may become active as a man or as a woman.

You don't know which.

Brown: And so, in the course of someone's lifetime, they can father a child; they can mother a child.

They can have lovers of all different types.

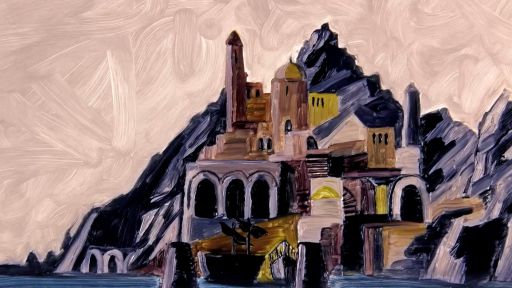

♪♪♪ [ Wind whistling ] Le Guin: In 'The Left Hand of Darkness,' we meet Genly, the first envoy from the Ekumen to the planet of Winter.

♪♪♪ -[Crowd whispering] -As he tries to navigate this icebound world of genderless people, Genly becomes entangled in a political web.

[ Whispering continues ] He's forced to flee across a glacier, along with Estraven, a native of Winter who has become his ally.

♪♪♪ Mitchell: As they cover the miles over the ice, they also close the miles between themselves, as individuals, as different subspecies of ♪♪♪ Le Guin: 'After all he is no more an oddity, a sexual freak, than I am; up here on the Ice, each of us is singular, isolated, I as cut off from those like me, from my society and its rules, as he from his.'

Mitchell: It's not just a geographical journey.

It's a journey into human cooperation, into a human relationship.

[ Wind whistling ] Gaiman: When 'Left Hand of Darkness' came out, it was perceived, rightly, as having changed things, as being something that was unlike anything else that had been published.

♪♪♪ Miéville: Nowadays, there is a lot more interest in kind of genderqueering and genderfluidity.

I wonder if it might be difficult for a young reader now to realize quite how extraordinary and powerful that was when she did it.

Goss: Readers and critics have thought about 'Left Hand of Darkness' as a feminist novel and I absolutely think it was, for its time, but, there were other writers, feminist science fiction writers, and critics, as well, who were saying, 'You didn't quite go far enough.'

Atwood: She got in trouble with 'Left Hand of Darkness' because, when you weren't changing into some other gender, you were 'he.'

Gaiman: It started getting criticism: 'Why are you forcing us to think of a masculine default all the way?

Couldn't you have done it a different way?'

Do I think that 'The Left Hand of Darkness' that Ursula would write now would be 'The Left Hand of Darkness' that I read in 1971?

No! Obviously not.

She has changed and the world has changed.

[ Birds chirping ] Le Guin: At first, I felt a little bit defensive, but, as I thought about it, I began to see my critics were right.

♪♪♪ I was coming up against how I write about gender equality.

♪♪♪ My job is not to arrive at a final answer and just deliver it.

♪♪♪ I see my job as holding doors open or opening windows, but, [scoffing] who comes in and out the doors?

What do you see out the window?

How do I know?

♪♪♪