THE WIZARD OF WAUKESHA By Dave Tianen, reprinted with permission from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

New York – For decades, arthritis has slowly devoured the talent in Les Paul’s hands.

The right essentially has become a stiff claw. The ring and pinkie are all that is usable on the left, and arthritis is eating away at them.

The right arm is mangled too, permanently bent at a 90 degree angle from a car wreck in 1948. There are seven screws in the arm, and the tendon in the elbow is shot.

Yet he continues to play.

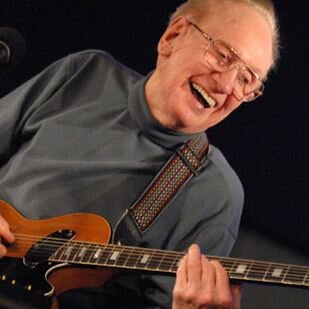

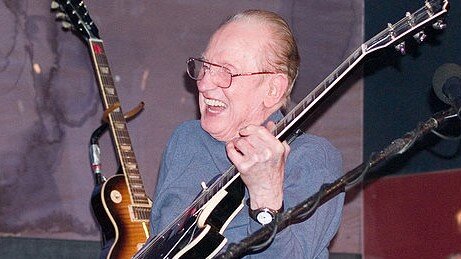

Every Monday night, the great guitarist carries his 92-year-old body and his 44-year-old Gibson onstage at the Iridium Jazz Club at 51st and Broadway. Still introduced as “The Wizard of Waukesha,” he does two shows – one at 8, one at 10 – in the basement nightclub.

Both are packed. Always.

Many, perhaps most, in the crowd weren’t even born in the early ’50s when Paul and his wife Mary Ford were major stars on TV and radio, topping the charts with a succession of hits: “Tennessee Waltz,” “Mockin’ Bird Hill,” “How High the Moon,” “Tiger Rag” and “Vaya Con Dios.”

That music helped define an era, but Paul ignores most of it now, opting instead for the standards he played during his jazz days in the ’30s and ’40s. It matters little.

Paul is that rare case where legend trumps celebrity. His last top 10 hit was in 1955, and he’s rarely seen on TV. But his great legacy has been blending the talent of a gifted musician with the skills of an inventor and engineer.

Influenced by the great gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt, Paul was one of the best and earliest electric guitarists. Along with a handful of players like George Barnes, Merle Travis and Charlie Christian, he changed the sound of popular music. And if Paul didn’t actually invent the solid body electric guitar (a fiction which he happily tolerates), he was a pioneer in its evolution, and he did more than anyone to popularize what would become the dominant instrumental voice of contemporary music.

His influence can be heard on almost every song on the radio, and musicians honor him with near reverence. Certainly no other Wisconsin musician approaches his impact on not just music, but popular culture.

Obsession with sound

A notorious fussbudget about sound, Paul arrives at the Iridium from his home in Mahwah, N.J., at 4:15 p.m., nearly four hours before his first show, so he has time to fine-tune the sound system. He is joined by his son and sound man Rusty, who lives with him, and another sound man. Since moving to its new locale at 1650 Broadway, the club has gone to great lengths to meet Paul’s demands.

“He made us change the whole sound system” club owner Irving Sturm cheerfully grumps. “We upgraded to like a $45,000 sound system, a Meyer sound system, because he is such a perfectionist. We did it, luckily for us, and the music has been very, very good. He’s a pain in the butt, a terrible perfectionist, he’s always bitching about something, but he’s always right.”

Of course, sound and its replication are a central part of the Les Paul saga. He is acknowledged as a father of multitrack recording, overdubbing and the electronic reverb effect. Multitrack recording had intrigued Paul since he experimented as a kid with poking extra holes in the sheets for his mom’s player piano.

In 1946, a gentleman named Colonel Dick Ranger approached Paul with a captured German tape recorder. Paul knew that Bing Crosby (whom Paul backed on a No. 1 hit in 1945) had been looking for recording techniques that would allow him to record at home. With financing from Crosby, and with the German prototype in hand, the Ampex Co. started making tape recorders.

Working in his own garage studio, Paul started to layer his own recordings. In 1947, he released a recording of the Rodgers and Hart standard “Lover” with eight guitars layered over each other. When “Lover” became a hit, he repeated the process and made a second hit, “Brazil.” Eventually, overdubbing became standard on his recordings.

It’s arguable that Paul’s impact on recording is as great as his impact on the evolution of guitars.

“I got a letter from Sinatra,” he says. “It’s a wonderful letter. I don’t remember the exact words, but he says if it wasn’t for you, I’d still be recording my first song. It was the multitrack recording he meant. Paul McCartney said the same thing: ‘I don’t care how much guitar you played, I don’t care how many hits you had, you invented that multitrack recording, and that made the difference.’ ”

Humble beginnings

Although he was a professional musician even as a child, Paul didn’t start out as a guitarist. Lester William Polfuss was born June 9, 1915, on North St. in Waukesha. The Polfuss family lived in an apartment adjoining the automobile garage Les’ dad operated. At age 8, Les was given an old harmonica by a construction worker, and within a year he was good enough to play in school talent contests.

When he was 9, his mother arranged for him to take piano lessons from a local woman who taught in her home. According to Mary Alice Shaughnessy, his biographer, after several lessons Les was sent home with a note that said: “Dear Mrs. Polfuss, your boy Lester will never learn music, so save your money. Please don’t send him for any more lessons.”

By the time he was 12, Les was making as much as $30 a week just playing for tips on the streets of Waukesha. About this time, Shaughnessy writes, Les acquired his first guitar, a $5 purchase earned by picking potato bugs off a local patch.

He also acquired a fascination with a regular on Chicago’s WLS Saturday Night Barn Dance called Pie Plant Pete. These were the early days of radio when live in-studio performers carried the programming load. Les idolized Pie Plant Pete, copied his sailor dress and even went to see him when the WLS troupe visited a Waukesha theater. Pete showed his fan some simple guitar chords and lighted a flame that continues to burn over seven decades later.

By the time he was 13, Shaughnessy relates, Les was a regular at local service clubs, talent shows and the Thursday night concerts at Waukesha’s Cutler Park band shell. At 17, going by the name Red Hot Red in reference to his hair color, he got an invitation to join Rube Tronson’s Cowboys, a regional country band. Within the year, Les had quit high school and become a full-time pro.

Through the 1930s, he followed one radio gig after another, moving to St. Louis and then to Chicago, migrating from his hillbilly roots to jazz and pop, and changing his stage name, first to Rhubarb Red and then to Les Paul. His big national break came in 1939 when, at age 24, he landed a job in New York with Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians, a big name band with a national radio show.

Developing ‘The Log’

Along the way, he kept tinkering with his instrument.

Hollow body electric guitars were being developed and commercially manufactured as early as the 1920s, but they were prone to distortion when amplified. When he was still in his Waukesha band shell days, Paul often found his acoustic guitar drowned out in a band.

He started experimenting with different ways to amplify the guitar. One experiment was to fill his hollow body guitar with plaster of Paris; it cut distortion but left him with a very, very heavy instrument. He apparently also tried mounting strings on an old railroad tie.

“He was an early innovator,” says Alan di Perna, West Coast editor for Guitar World. “There were other people who were technical innovators, but they didn’t play like Les did.”

By 1941, still only 26, Paul had fashioned a workable solid body guitar he dubbed The Log, since it was essentially a four-by-four block of solid pine with a tailpiece, two pickups and a Gibson neck mounted on it. Later, for appearances, he fixed two side wings from an Epiphone guitar so it would actually resemble a guitar.When he approached Gibson Guitars about the commercial potential of The Log, Shaughnessy reports, they told him it was “nothing but a broomstick with a pickup on it.”

By the early ’50s, Gibson started to revise its view of solid body electric guitars. A California engineer named Leo Fender had introduced a commercial solid body electric guitar, and Gibson didn’t want to get left behind. Their design department quickly put together its own version, and went to Paul seeking his endorsement.

So it was that in 1952, the Les Paul Guitar arrived, although Paul himself had contributed only minor elements to its design. The endorsement deal made him wealthy, and the brand name made him a legend.

Shaughnessy says: “Gibson made extraordinary guitars. That is why Les’ name lives on. It is not because of the four years of hit making. The reason he’s going to live long past his musical contributions is because of this extraordinary guitar that bears his name.”

As for The Log, it’s now in the collection of the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Retirement and rebirth

During World War II, Paul was drafted into the Army, where he became a regular player for the Armed Forces Radio Service, or AFRS. Paul served his country living at home in Hollywood and playing on the radio with the biggest names of the day. After leaving the Army, he hooked up with the biggest recording act in the world – Bing Crosby – and in 1945, he and his trio scored their first No. 1 hit, backing Crosby on “It’s Been a Long Long Time.” Other hits followed. In the late ’40s, Paul linked up with a sweet-voiced backup singer for Gene Autry named Colleen Summers. Paul renamed her Mary Ford, and she became his professional partner. In 1949, he split with his first wife, Virginia Webb Paul, (the couple had two sons, Rusty and Gene) and married Ford on Dec. 29 of that year in the Milwaukee County Courthouse. At the time, the couple was in town for an extended engagement at a club called Fazio’s.

The couple eventually adopted a daughter, Colleen, and had a son of their own, Robert.

By the early ’50s, Les Paul and Mary Ford were one of the biggest acts in the music business, with a TV show, a radio show and a string of hit records. In the mid-1950s, though, the country’s taste in music changed almost overnight. Paul and Ford had one last top 10 hit, “Hummingbird,” in 1955.

Then rock ‘n’ rollers crushed his career with the very instrument he’d given them.

As his and Ford’s professional lives nose-dived, their marriage frayed as well. They were divorced in 1964.

On top of everything else, health was becoming an issue.

“The main reason I retired was because I injured this arm, this finger. I had surgery on it in ’61. That was the beginning of my hand problems,” Paul says. Other health issues piled on top of the arthritis. In 1969, a friend playfully cuffed him on the head and broke his right eardrum. Three operations followed, but there was permanent hearing loss.

There was one bright spot: In the late ’70s, he made a Grammy-winning comeback with fellow guitar legend Chet Atkins on the album “Chester and Lester.” Then came more health problems. There was a heart attack followed by bypass surgery.

“Then came a funny thing. The doctor called me in his office,” Paul recalls. “He said, ‘I want you to promise me two things. One, I want you to be my friend, and two, I want you to work.’

“I said, ‘I thought that’s what got me in here.’

“He said, ‘Hard work never hurt nobody. I want you to promise me you’ll go back to the clubs.’

“So they wheeled me into the room and I asked the nurse for a piece of paper. I drew a line down the middle. I wrote down all the things I didn’t like, the things I couldn’t do. And I wrote the things I would like to do if I went back to work.”

Paul knew exactly what he wanted to do.

“For my whole career, all the things I’d done, nothing impressed me as much as just playing in a little club. There’s no pressure. You can do what you want to do.”

In his late 60s, already set for life financially, Paul started looking for work.

“I looked all over. I came to New York and I looked for a place. I finally walked up to the maitre d’ of the place and said, ‘My name’s Les Paul.’

“He said, ‘How many will be seated?’

“I said, ‘I don’t want to be seated. I want to talk to you about a job.’

“He looked at this old guy and thought, ‘He wants a job here?’

“So he said, ‘What kind of work do you do?’ – figuring I was going to wash dishes or something like that.

“I said, ‘I’m a musician. Obviously you’ve never heard of me.’

“I asked if he had an owner. I walked over to the owner and introduced myself to the owner and he said, ‘Not the Les Paul?’

“I knew that was good.

“He said, ‘What are you doing in this joint?’

“I said, ‘I’m looking for a job. I want to go to work. I want to come in here and play with a trio one night a week.’ I said, ‘I hear you’re closed on Monday.’

“‘Yeah,’ he said, ‘We’re closed. I don’t know how we can work that out.’

“I said, ‘Well, I’ll work for nothing.’

“He said, ‘We’re open Mondays!’ ”

Back to the stage

From 1984 to 1995, Paul, backed by Lou Pallo on guitar and Wayne Wright on bass, was a Monday night fixture at Fat Tuesdays. But the hands continued to get worse. To cope with the pain, Paul took medication, which eventually gave him an ulcer. There was no choice but to quit playing.

While Paul was mending, he got a call from Ron Sturm, the owner of a new jazz club in New York City.

“He said, ‘When you’re ready, I want you here. No matter what the deal is, we’ll top it. We want you.’ So I knew I had a home when I got well enough,” Paul recalls.

Still, when he came to the Iridium in 1996, he had doubts.

“I thought, ‘What am I going to do? I can’t play like I used to. I can’t do what I used to do. The hands are all messed up. What am I going to do?’ … I’d been away from it for a year. I went up there and the audience seemed to not mind at all.

“It was at that time that a woman came over to the bar. She said she didn’t want to drink, she just wanted to talk to Les Paul. She was a nurse. She said, ‘I came over here to tell you something.’ She said, ‘Many of the people who are coming in to see you are coming because of what you used to do, but they’re not expecting you to do what you used to do. They’re expecting to see and hear what you can do now… .’ She made me understand that if Joe Louis got into the ring at 75, he’s not going to be what he was when he was 20. And nobody expects him to be that. So with that in mind, I went up on the stage with an understanding of myself, what I could do and what I couldn’t do and I could live with it. And it worked.”

Deep, wide imprint

Paul’s influence continues to ripple through rock, jazz and country. All Music Guide describes his style as “astonishingly fluid, hard-swinging” with “extremely rapid runs, fluttered and repeated single notes and clunking rhythm support.” It was a style that carried him easily across musical boundaries. The late Atkins, surely the most influential of all country pickers (and an important architect of the Nashville sound), always cited Les Paul as a major touchstone.

“The story’s been repeated of Les coming to Springfield, Missouri, and seeing Chet play at KWTO and Chet, not knowing that Les was watching, was trying to impress this guy who was paying special attention to what Chet was doing,” recalls Jay Orr, senior museum editor of the Country Music Hall of Fame. “Then later he found out that it was Les Paul. Chet felt a little bashful because he had been showing off with some of Les Paul’s patented licks.”

Although he’s never played rock ‘n’ roll himself, Paul’s imprint has been felt on rock since the beginning.

Many second generation ’60s rockers grew up listening to the Ventures and their guitar hits, such as “Walk, Don’t Run” “Perfidia” and “Hawaii 5-O.” Bob Bogel of the Ventures says Paul was a huge inspiration to his band.

“We were influenced by him, but we didn’t try to play his style,” Bogel says. “He was way too accomplished for us… . I’ve always admired his work and I’ve always been a huge fan of his. In interviews they’d ask us our influences and we’d always say The Big Three: Les Paul and Chet Atkins and Duane Eddy.” Today major rock guitarists such as Eddie Van Halen, Eric Clapton, Paul McCartney, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Slash have acknowledged their debt. Jazz musicians pay him homage as well. Some of the highest profile players in the world, such as George Benson and Al Di Meola, are huge fans. Di Meola played at Paul’s 88th birthday party at the Iridium.

At his Monday night shows, brother celebrities come to pay homage almost as a matter of course. Tony Bennett. Harry Belafonte. Brian Setzer. George Benson. Paul McCartney. Jeff Beck. Paul Shaffer. Keith Richards.

Reflecting on the common heritage shared by such disparate artists and styles of music, blues rocker Jon Paris says, “All roads lead to Les.”

In his element

In the late afternoon, the basement jazz club is deserted except for staffers setting out gray tablecloths and place settings. Vintage jazz posters dot the walls: Cab Calloway at the Cotton Club … Benny Goodman at some hotel in Pittsburgh. Diana Krall’s version of “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” is heard through the monitors. Although reputed to be “richer than God,” the old guitarist carries his Gibson solid body in a battered case with frayed edges and duct tape wrapped around the handle.

A notoriously indifferent dresser, Paul is resplendent by his standards: black slacks and a short black jacket over a burgundy turtleneck. Perched on a stool, fussing over his guitar, he has an almost professorial countenance. The pudgy frame he had in his prime has thinned and withered. The carrot hair has whitened and thinned. He wears glasses, and there are hearing aids in both ears. Still, for a man edging toward 90, he moves fairly well. But when he walks only the left arm swings. That crooked right arm just hangs.

Gradually the rest of the band drifts in. Rhythm guitarist Lou Pallo has played with Paul off and on for 40 years. Acoustic bassist Nicki Parrott, 32, is a much newer addition. She came to the states from Australia on an arts council scholarship and stayed, and has been playing with Paul for 21/2 years. Joining them tonight will be guitarist Howard Alden, a boyish 40-year-old with an imposing list of jazz credits. The sound check/rehearsal material anticipates the sets: “All of Me,” “Begin the Beguine,” “Caravan,” “Tennessee Waltz” done as a guitar boogie.

“He rehearses the same material week after week,” says Iridium co-owner Ellen Hart. “He’s very precise. Everything has to be exact.” Eventually, Paul gets the sound where he wants it and the band heads backstage for a chicken dinner. Here, Paul is perhaps even more in his element, greeting visitors and holding court.

A thirtyish documentary filmmaker is sitting next to Paul on a couch, and she scratches his back while they chat. She stops for a moment, and he pipes up with, “OK. My crotch itches now.”

Without a pause she fires back, “I can take care of that!”

Nurturing Waukesha tie

Paul claims he’s busier than ever, no small boast from a man renowned as a hard pusher who continues to live on what Nashville calls Central Elvis Time. He rarely rises before noon or 1 p.m. and stays up typically until 4 a.m. This day, he will do two one-hour sets at the Iridium, sign autographs until midnight, do two radio interviews and eventually turn in back in Mahwah around 8 a.m.

“His pace is go-go-go. Even now,” says his friend and biographer Robb Lawrence, who lived with the guitarist for several months in the mid-’70s. Paul is working on two books and coordinating Les Paul exhibits at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, the Smithsonian Institution and the Waukesha County Historical Society & Museum.

Although the Historical Society is still fund-raising and hasn’t set an opening date, Executive Director Sue Baker says: “It will be the showcase exhibit in the museum. It will be 5,000 square feet. It will be large and hands-on. When you walk in, you will walk into Les’ world in Waukesha.”

Paul clearly loves to reminisce and spin tales about the old days. Lawrence says, “Les has a great sense of humor, and he is known to create tall stories for the love of it.”

Shaughnessy agrees. “He overwhelms you with stories,” says the author of “Les Paul: An American Original,” published in 1993. “He’s a champion storyteller. Half of it is bull, but it’s fun to listen to.”

Bing Crosby is clearly a favorite topic. Working with Crosby on radio, Paul backed such legends as Bob Hope, Jimmy Durante, W.C. Fields, the Andrews Sisters and Frank Sinatra. He claims to remember being there the first time Crosby and Sinatra met. He recalls Crosby was wary before the show.

“Bing was in the men’s room. So I go in the men’s room and I’m right next to him and Bing says to me, ‘Can the kid sing?’ That was his question.

“I said, ‘I’m afraid so.’

“So I walked out and he was still in there washin’ and puttin’ his wig on. So I walked out and Hedda Hopper (the gossip columnist) was there. I was leaning against the door. She said, ‘Have you seen Bing?’ I said, ‘Yeah, he’s in there.’ She said thanks and she went in.

“So Bing comes out and he says, ‘Where’s that goddamn redhead?’ ”

A special night

Business interrupts the backstage chat. It’s showtime. The Iridium introduces him as “The man who changed the music for all of us – The Wizard of Waukesha – Les Paul.”

The stories continue on-stage. Some of them are awful jokes at the expense of Pallo. And there’s lots of benign flirting with Nicki Parrott. He tells the crowd she makes him feel like an old building with a new flagpole.

She rejoins with a randy blues song: “I’m an evil gal, Les; I like older men; think they’re the best; One night with Les and you’ll forget all the rest. Les, get that Viagra.”

Woven into the comedy are the songs: “Sunny Side of the Street.” “Blue Skies.” “Over the Rainbow.” “Someone To Watch Over Me.” “It Had To Be You.” “The Sheik of Araby.” “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.” “Sweet Georgia Brown.” One of the old hits with Ford – “How High the Moon.” Paul even sings “Bill Bailey.” Everybody gets to solo, and there’s clearly an effort to rest that ailing left hand.

During the second set, the guests start to come up. There’s a dancer friend of Parrott’s named Roxane Butterfly. She tap dances to “Tea For Two” and the crowd loves it. Old friend and fellow Wisconsinite Jon Paris comes up. With him tonight is former Muddy Waters band member Steady Rollin’ Bob Margolin. Margolin romps through an impromptu “Don’t Let Me Kill This Woman Please.”

Everything works. The crowd loves Margolin. They love Paris. Most of all, they love Paul. For an encore, he does “Paper Moon.”

“This is a wonderful night for us,” he tells the crowd.

After the show, he sits at a table in back of the club and signs autographs and poses for pictures for two hours. A line of perhaps 60 people stretches through the club. Everybody gets an autograph, a picture or both. Some get two or three autographs.

The left hand is still iced, but Paul sits patiently, sipping a Haake Beck non-alcoholic beer, chatting and posing for pictures. He signs books, CDs, pictures, programs, guitars, ball caps and body parts. A professor from Texas, in New York with a group of students, insists he sign her breast with a felt pen, and he cheerfully obliges.

“I sign lots of boobs,” he says.

The fans, who appear to range in age from early 20s to early 60s, approach Paul with a mixture of good cheer and awe.

“Mr. Paul, I can’t say what a privilege this is. My whole life I’ve been waiting to meet you… . ”

“Can I have a hug?”

“Hi Mr. Paul. It’s a honor to meet you… . Thank you for all you’ve done. It certainly made my life more enjoyable.”

Everyone gets a moment, and Paul seems to love it almost as much as they do. And yet there’s a part of it that still mystifies him.

He mentions it while leaving the club.

“Bing asked me, ‘Why do people like me?’ He didn’t know. I don’t think he or Sinatra understood that. I’m the same way. I have no idea why people like what it is that I do.”