Director/producer John Paulson has made numerous films on music, fine and performing arts, history and the cultural traditions of the world.

Director/producer John Paulson has made numerous films on music, fine and performing arts, history and the cultural traditions of the world.

With AMERICAN MASTERS Les Paul: Chasing Sound, he turns his attention to an extraordinary musician and inventor. Below, Paulson offers some insight into the legend:

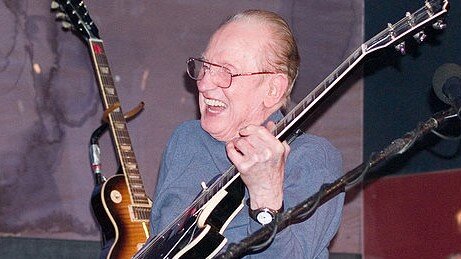

Q: The film is basically focused on Les Paul’s 90th year on this earth, right?

A: Yes, it’s extraordinary; he’s still going as strong as ever and that’s why we love the title Chasing Sound, because we spent most of two years chasing after him. For a 90-year-old to wear us out like he did, it’s a testament to his non-stop drive and the pace he’s kept all of his life. When we first approached Les to do a documentary on his life he was 88 years old and just too busy chasing the sound, so to speak, to think about working with us. Finally, of course, we were fortunate enough that he gave us the time and now, two years later, we have this film documentation of his originality and incredible vitality. Les Paul’s 90th birthday year essentially became for us the framing device around which the film celebrates his long and fruitful life on this earth.

Q: Take us back to the beginning when you said to yourself, “I’m going to make a documentary on Les Paul.”

A: I had been working at the Smithsonian Institution as a filmmaker for many years making films on historical figures, traditional culture, the arts, and I was really tied into the music and performance side of things. In 2002, I was looking for projects and had this notion that Les Paul would be a great subject. I just couldn’t fathom that a comprehensive film biography hadn’t been done on somebody who’s so extraordinary, not only as a musician but as an inventor with such a vast impact on our cultural lives, which makes him a perfect subject for an AMERICAN MASTERS film.

Also, the story was so rich from the point of view of his longevity, of the vast swath of musical and technological history that his life has spanned. So I teamed up with my partner, writer and co-producer Jim Arntz, who knew his way around the PBS world, and we took our idea to the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. We knew that Lemelson had an abiding interest in Les because, look, here is a guy who had visions for what the world could be, musically, sonically and who invented the tools to achieve that vision. Not only that, he also popularized his own creations and was still alive to talk about it. The Smithsonian provided us with a little seed money with which to shoot the 90th birthday show at the Iridium Jazz Club in New York City, and we used that footage to create a six-minute piece that attracted our financial partners – Glenn Aveni, Icon Television Music and Susan Lacy, executive producer of AMERICAN MASTERS.

Q: One thing many people may not realize is that Paul still performs. Your film captures that aspect of him, where he shares the stage with guests who sit in and jam.

A: It’s really a testament to Les’ sense of adventure and his generous spirit that at 92 he’s still welcoming people onto the stage every Monday night, two shows a night at the Iridium. At times, it’s like an old vaudeville show – there’s a tap dancer, a trumpet player, a jazz vocalist. And, of course we were fortunate enough to be there on his 90th birthday, when people like Steve Miller, Tommy Emmanuel, Stanley Jordan and others were there to perform. The connection between Les and Tommy Emmanuel that you see in the film was really something special, and in the end that big smile on Les’ face and the twinkle in Tommy’s eye just says it all.

Q: You tell such a broad story, the all-American rags-to-riches tale of a kid from a midwestern small town who realizes his big dreams. But, as Paul has often said, many people just think he is a guitar.

A: It’s true, and I think most people, even if they know Les Paul actually exists as a human being, will be surprised when they’re reminded in the film of his many accomplishments and the important points in music history that his life has touched. He is a self-made guy in the classic American sense. He’s a guy who recognized his gifts early on and nurtured them and never let anything stand in the way of his success. And the gifts are broad. The guitar playing and arranging that he did on those pop tunes of the late 1940s and 1950s, first as a solo artist and then with his wife Mary Ford, really stand out as extraordinary artistic accomplishments.

As Steve Miller says in the film, Les could “really burn the frets off the guitar” in those days, and I believe Les is largely responsible for bringing the electric guitar to the fore as a solo instrument. But he did it with such taste and style that people were barely aware that it was happening. In other words, his music is so infectious, and the arrangements and guitar work so canny and unprecedented that it came across as great listenable music and not simply technical wizardry that called attention to itself. Then again, on the technological side, he had the gift to understand the recording limitations of his day and simply dreamt up something better. In the 1930s and ’40s it was the layering of multiple guitars using a pair of disc recording lathes, in the ’50s it was the switch to tape machines and sound-on-sound overdubbing, and finally the invention of multi-track recording, which today is the industry standard. He really did change the music.

Q: Were you surprised to discover that prior to Paul’s big hits of the 1950s, he was a major jazz artist?

A: Les’ life sprawls from country to jazz to pop to rock, and then back to what he calls “middle of the road” jazz. But yes, what surprised Jim and me most was that Les was there during some of the most fertile moments of jazz, and trading licks with some of the greatest figures in jazz history – Nat Cole, Art Tatum, Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Duke Ellington, Lester Young, Teddy Wilson, Count Basie, Charlie Christian, the list is endless. Les had a sixth sense for where great music was happening and from whom he could steal licks and add to his repertoire. That’s, of course, how he learned, and he progressed like lightning. He says of his playing at that time, “You just couldn’t hold me back. I was a racehorse.” I’m especially happy the film was able to illuminate that side of Les’ early musical experiences. It was truly a revelation to us.

Q: The 1930s sound like a rich period in Les’ formation as a musician, with many different experiences influencing his tastes and playing style. What about the electric guitar – didn’t he also began his experiments with the guitar in that period?

A: That’s right. He began experimenting in Chicago in the mid-’30s, and by 1938-39, when he and his trio were playing in New York with the Fred Waring radio show, Les had built himself an electrified hollow body at the old Epiphone Guitar factory on 14th Street. It was quite a contraption with iron bars inside bracing the body against vibration to achieve sustain, the pickups were hand-wound, and he used a coat hanger for a vibrola bar. You have to remember at that time, he couldn’t go down to the store and buy a solid body electric; he had to make it himself. With Waring, Les would do two broadcasts, one for the East Coast and one for the West, and he’d play acoustic on the early show and electric on the later show and then they’d go back and listen to the transcription and see which they liked. Ultimately, they came out in favor of the electric guitar, and Les may have been the first guy to play the electric guitar on the radio coast to coast across America. We can’t verify that but it could be true. And what do you suppose all the guitar players around the country listening to Les’ licks on his homemade electric guitar were wondering? Bucky Pizzarelli told us he had the Fred Waring station marked on his Philco radio dial so he could tune in to Les’ magical sounds.

Q: You managed to come up with rare archival footage and some early performances. Of all the footage, what is especially memorable?

A: I think for me the favorite is a charming little clip that comes about three-quarters of the way through – a newsreel we dug up from the early 1950s, when Les Paul and Mary Ford are having their biggest hits. Les and Mary come through the door of their Hollywood home – it’s a modest little bungalow with leafy wallpaper – they’ve just come home from “a Hollywood premiere.” She’s in fur and he’s in a fine suit. As they enter the living room, you realize there is nothing but recording equipment, guitars, machines, meters, knobs, and dials – everywhere. There’s no place to sit, and this is their home and this is where they made their music. The newsreel continues and they introduce some their hit tunes and it’s just a delightful moment, mainly because it’s rather unguarded. It’s not a posed or scripted publicity appearance. I think it really points up a central aspect of Les’s innovative nature – that when he was creating all those hits, nobody but nobody in the business that I’m aware of was recording, arranging and writing their own tunes, in their own home, in the basement, bedroom, garage, whatever room sounded best for Mary’s vocals. The bathroom, because it had better reverb, was often used to track the vocals. Then he delivered the masters to Capitol Records and Capitol packaged them and put them out untouched. I can’t think of anybody else at that time who had similar abilities or could even dream of having that kind of creative control. And of course the music that poured forth from Les Paul’s Curson Street bungalow in Hollywood speaks of just what an innovative giant he was, and at the same time the stature he had in the industry. He was the recording industry’s first “do it yourself” pioneer.

Q. The film has a “behind the scenes” aspect to Paul’s current life as well.

A: Yes, Les truly opened up his home to us and allowed us that very privileged view into his private life. And to answer preemptively, yes, that is his living room and his bedroom amid all the clutter. His whole house is essentially a museum. His bedroom is the guitar storage room, his living room is the recording studio, his recording studios are storage rooms for inventions, some past and others ongoing. Les was so kind to step us through all of it, so we see the first sound-on-sound recording machine, we see his home-made disc recording lathe he made using a Cadillac flywheel from his dad’s auto garage, we see eight-track recorder number one, we see Django Reinhardt’s guitar and the first prototype Gibson Les Paul which was sent to Les from the factory back in 1953. I mean, it’s really an unprecedented view into Les’s life, and the hard evidence – the artifacts of his genius – are all on view here.