American Masters – Lon Chaney: A Thousand Faces premiered on PBS in 2000.

When we think of the silent film era, we think of actors like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, or Clara Bow, stars who created trademark personas and spent their entire careers testing the limits of those characters. They perfected what they had created, but rarely attempted other roles. For many in the industry, both then and now, this type of career is considered the pinnacle of success, but for one actor it was the antithesis of the his art. For Lon Chaney, the art of acting was the art of continual transformation, and it came from a desire to become someone else, to leave his own skin and enter another’s.

Chaney’s childhood and early career

Born on April 1, 1883, in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Leonidas Chaney was one of four children born to deaf parents (his maternal grandparents founded Colorado’s first deaf school in 1874). As a result, Chaney learned how to communicate with his hands and face while growing up, expressing a variety of emotions without ever uttering a single word. At an early age, he was familiar with what it was like to be an outsider, to be at once a part of the everyday world and simultaneously distanced from it. This, more than anything, informed his choice of roles and provided him with the sensitivity to perform each of them extraordinarily well.

In his early teens, Chaney was introduced to the theater and worked as a prop boy at the local Opera House. In 1902, at age nineteen, he made his theatrical debut in an amateur play, and soon after joined a traveling musical comedy troupe. During this period, Chaney’s ability as a graceful dancer and developing comic actor began to take shape. In 1905, while playing in Oklahoma City, he met a young singer named Cleva Creighton. The two traveled and performed together, and were soon married. The following year Cleva gave birth to Creighton Chaney (or, Lon Chaney, Jr.). The couple’s early married years were rocky, and in 1913 Cleva attempted suicide by drinking poison in the wings of the Majestic Theater in Los Angeles, California, where her husband was performing. Though she lived, her vocal cords were permanently damaged and her singing career was finished. Soon after, Chaney filed for divorce and won custody of his son. The stigma of such a public tragedy forced Chaney to leave the theater, and he entered the growing industry of motion pictures.

It is unknown how many films Chaney made during his career (the official count stands at 157), given that he appeared as an extra in numerous films at Universal Studios. He was so adept at changing his appearance with makeup — a trade he learned during his many years on the stage — that Chaney forsook the leading-man roles and went for character roles instead. During his five years at Universal, Chaney essayed numerous types of characters, a trait that would later make him famous, and occasionally wrote and directed as well. In 1919, he made his mark in “The Miracle Man,” in which he played a bogus cripple who, along with other criminals, takes advantage of a blind faith healer only to be swayed by the goodness of the patriarch. After this performance, Hollywood began to notice Chaney. One of his other impressive roles during this period was as the legless criminal in “The Penalty” (1920). To simulate a double-amputee, Chaney devised a leather harness with stumps that allowed him to strap his legs behind him and walk on his knees.

Chaney’s rise to fame

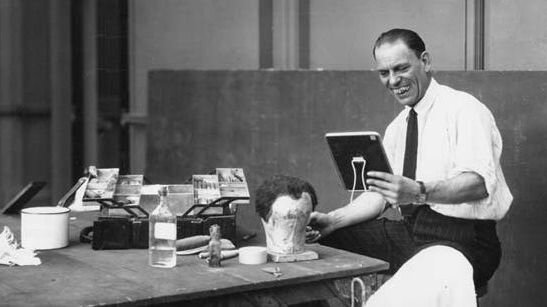

Two of Chaney’s best-remembered films are also considered classics of the silent era: “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (1923) and “Phantom of the Opera” (1925). In both films, Chaney dominates the subject matter and etches a distinctive personality. He was capable of not only repelling audiences with his character’s visage but generating a tremendous amount of empathy with them as well. In both films, Chaney completely distorted his own face by using wax, false teeth and greasepaint. To become the hunchback Quasimodo, he faithfully copied Victor Hugo’s description. When Chaney was finished with the makeup, it was as if the hunchback of Hugo’s book had walked directly off the pages. The same was true for the Phantom. Chaney carefully recreated the details of the Phantom’s face (described as a living skull) onto his own by using several tricks of the makeup trade. He once said that “the success of the makeup relied more on the placements of highlights and shadows, some not in the most obvious areas of the face.”

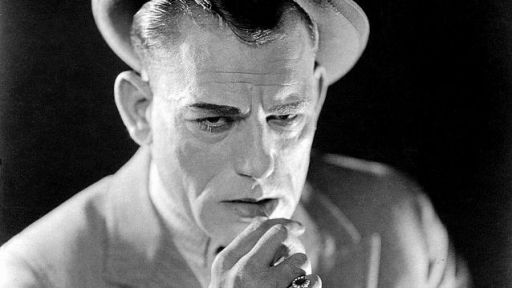

By 1923, Chaney was known a “The Man of a Thousand Faces” for his ability to transform himself into any type of character. His roles ranged from pirate, to Chinese shipwreck survivor, to tough Marines sergeant, to Russian peasant during the Russian revolution, to Mandarin, to circus clown, to crusty railroad engineer, to Fagin in “Oliver Twist” (1922). His gift for playing a vast array of characters even made him the subject of a popular joke at the time: “Don’t step on that spider! It might be Lon Chaney!”

Chaney’s work with Tod Browning

Chaney’s collaboration with director Tod Browning was a successful one for both artists. Working together at Universal Studios in 1919, the duo hit their stride while both were under contract to MGM Studios. Browning, a former sideshow performer and vaudevillian, crafted stories that were a combination of the macabre and tragic romance. With Chaney, Browning often came up with an idea of a character and then used that character to fashion a story, as he did for what is considered to be one of the best films the two artists ever made, “The Unknown” (1927). Chaney plays Alonzo, an armless knife thrower, who hides out from the police in a local circus. Actor Burt Lancaster once commented on Chaney’s performance that in one particular scene, Chaney gave “one of the most compelling and emotionally exhausting scenes I have ever seen an actor do.”

Chaney was very press-shy, making a rare attendance at a movie premiere, granting few interviews, and often claiming that “between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney.” Mostly, this was done as a publicity ploy on Chaney’s part to keep the public guessing and coming back for more in his next film. Away from the camera, Chaney was an avid fly-fisherman, enjoyed camping with his second wife, and entertained a small circle of friends in his Beverly Hills home. He was often described as looking more like a modest businessman than a major movie star. He was extremely helpful to struggling actors (he once gave a then-unknown Boris Karloff some helpful advice), as well as being a champion of the crew members on the studio lot. Once, he was seen placing some baby birds back into the nest out of which they had fallen, and begged a witness not to tell anyone: “I will never hear the end of it. Everyone thinks I am so hard-boiled!”

Chaney’s legacy

When he died at the age of 47, Chaney had acted in more than 150 films and was arguably the most beloved film star of the late 1920s. He was not only a great actor, but he had become an authority on the art of make-up, helping everyone from Will Rogers to Jack Dempsey. He even wrote the ‘make-up’ entry for the 1929 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. (He was also a recognized authority on penology and authored many articles on the topic.) Unlike so many of his peers, Chaney entered the world of sound films with the same grace and proficiency he had shown throughout his career. Seven weeks after completing what would be his only talking picture, Chaney died. All throughout Hollywood, studios observed a moment of silence in his honor. Fellow actor Wallace Beery, who said that Chaney “was the one man I knew who could walk with kings and not lose the common touch,” flew his plane over the funeral and dropped wreaths of flowers. Despite his untimely death, Chaney left an unmistakable mark on Hollywood cinema and gave us a glimpse into the souls of outsiders who were different from the rest.

Special thanks to Michael F. Blake for sharing his expert knowledge of Lon Chaney with American Masters Online.