TRANSCRIPT

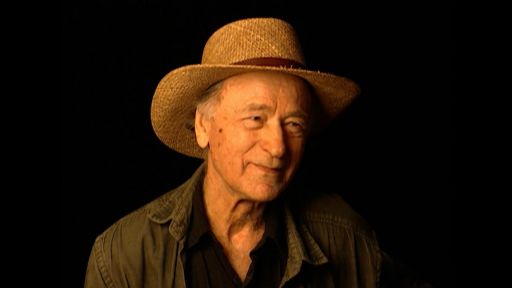

- Well, New York City, it was an early transition.

It was the birth of the hippies, and then the anti-war statements, and I played a little guitar down in the coffee shops, and ran the hootenannies.

And then the British took over all the theaters on Broadway.

There was "My Fair Lady," there was "Hamlet," there was "Separate Tables."

They took over 99% of theaters, and Off-Broadway began with the Edward Albee's, and that's where Carol Burnett was in "Once Upon a Mattress," and there was "The Fantastics," and we got together in 1960 at Second Avenue and Eighth Street, and we did Jean Genet's production of called "Les Negres," "The Blacks."

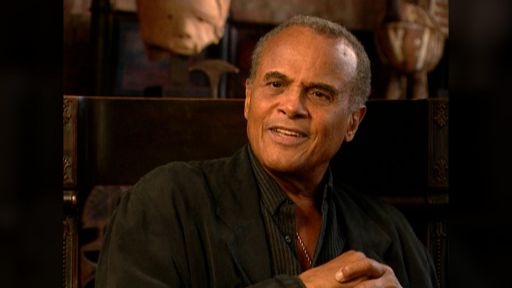

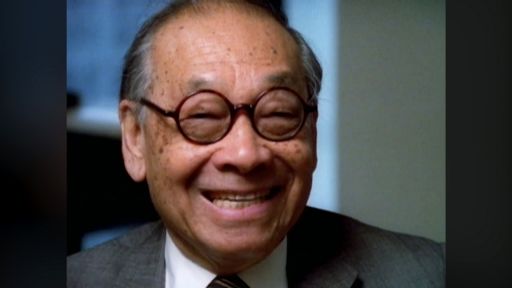

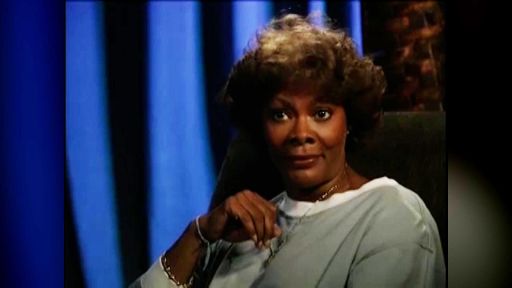

And in that cast was Roscoe Lee Browne, James Earl Jones, Godfrey Cambridge, Charles Godone, Lex Monson, J.

Flash Riley, Abbey Lincoln, Cicely Tyson, and of course, Maya Angelou.

So we got together to do "The Blacks," and it lasted five and a half years, so we kind of made an indelible impression upon the world public by doing Jean Genet's "The Blacks" at the St. Mark's Playhouse on Second Avenue and Eighth Street, and Off-Broadway has never been the same.

That's where when we finished, the Negro Ensemble took over the same building.

That's when I first met Maya Angelou (indistinct).

She was the combination, and Jean Genet who wrote it, combination of everything that Queen Elizabeth, all the royalty, the white female royalty of Europe, all these centuries and centuries amounted to my royalty, what I say goes, and all that stuff.

And then there's the Black queens that, oh, that it was so beautifully written between Roxie Roker and Maya, and how the director made a dance out of it, so it was like a cock fight, but a poetic cock fight.

And then Cicely Tyson playing the young Black lady, and she would mock, and one of her lines was, "I am the lily white queen of the West, only centuries and centuries of breeding can make me, and I have," since she's walking up this (indistinct), and it was a, it was a derision, but a very poetic derision, and raised the consciousness of race to such an element that it's called the theater of the absurd.

Racism is absurd.

We'd have the audience, and there was a little subterfuge in the ushers and usherettes, and they were put into this ambiance even before the play started that they've gotta lock the doors.

And we started with the locking the doors and the secrets, and then finally we started with a waltz, mocking them.

And then all of a sudden, Roscoe Lee Browne would say, "Ladies and gentlemen," and the entire cast go, "Ha ha ha ha," and that started the whole thing.

And people just wondered, what kind of play have we come to see here?

But it's a clever depiction of how we feel when they do certain things, and was done in a beautiful artistic way.

But it frightened a lot of people, 'cause they had no idea that they were doing it, so there's a fright there.

So now that we know we're doing it, then you're angry, what you gonna do to us kind of emotion.

So there's a fear, and there was one woman fainted, and a man had a heart attack, 'cause we were so influential and impressionable that we thought that we had them prisoner.

That's one of the ambiences of the play within the play.

So I guess we did it well enough for that reaction to happen, and that was the meaning of "The Blacks."

It was the play whose time had come.

It was the statement whose time had come.

It was the Malcolm X time, it was also the Dr. King time.

And then we had the sensitive audiences who loved it and came back.

Jane Fonda came back about 100 times.

And we had some very diplomats come from around the world to see it.

And it was so riveting, because what it was was a secret ritual that we got this audience and held them captive while we tell them our story.

It was just absolutely electric, and when it was over and they realized it was just a play, sometimes there was no applause, but they were so impressed with what we did.

But that was a play whose time had come, and it gave birth to a lot of other things.

Oh, now you can say that?

So let's go with James Baldwin now, and let's go through, well, then "A Raisin in the Sun."

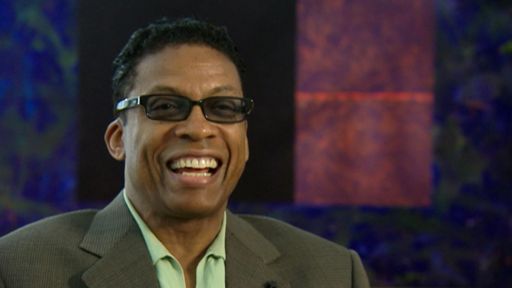

We came from "Raisin in the Sun" to that, and then all of a sudden plays like it and statements like it from all ethnic groups started to hit the boards, and then movies started to come, LeRoi Jones, Amiri Baraka, and all of a sudden they had a voice.

Music had a voice.

It was time, it was a renaissance time for all factions.

And we were together, we were a whole bunch of people.

There was two different sections.

There was the Black things.

We'd all go uptown and have chicken and waffles, and have parties, and the party times was hilarious with her and Godfrey Cambridge and Josephine Premice.

I remember Lena Horne, I remember all of those people, and we kind of, it was a tribe of people, but then again, we started having parties with the Jane Fondas, so it transcended into this wonderful renaissance kind of society.

That was offstage, but it was impressionable enough so that when we did performances, those people would show up and bring their friends.

So the society grew and grew and grew, part of that renaissance of art that happened for about 50 years there.

I grew up in Brooklyn with some of those teachers, and they still were alive, still my friends today as a result of that society.

- [Interviewer] Did you have any stories of Maya at that time?

Obviously, you must have spent a lot of time hanging out with her as well.

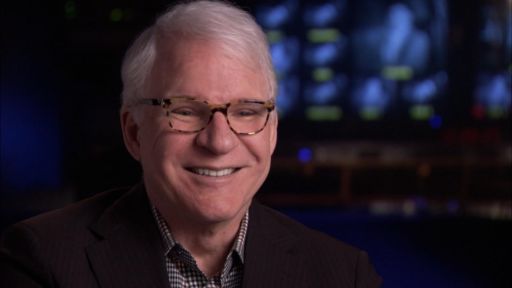

- Oh yeah, hanging out with Maya was, at the time, I was this young actor, you know?

I had done "A Raisin in the Sun."

I had started at the age of 17, and I had the kind of a, I called it a milkshake kind of life.

You know, I didn't have any consciousness and racial consciousness or anything.

I was very fortunate to get all this work.

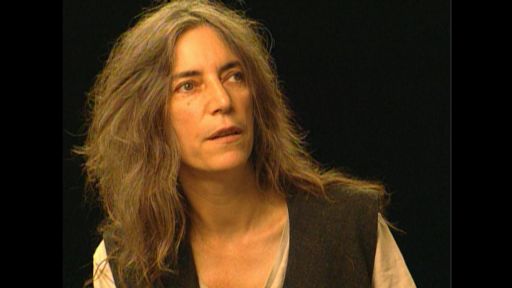

So that deep abiding culture, Maya was responsible for teaching me why I should be upset, why I should know more about my roots, why I should behave in a certain way, and it spread.

Her influence spread into the jazz musicians and the young people at the time.

It was the afros, the dashikis, and I eavesdropped a lot, and I sat at around her to listen to her and her contemporaries.

And I saw her with Malcolm X from time to time, and people like that, and I listened and listened and listened, and planted those seeds back away, never forgot what she said.

But she was like that early, much more angry, much more angry at the injustice, and that kind of mellowed out as she kind of grew, and with her influence, she became a poet, and she became smoother, but the philosophy remained the same.

- [Interviewer] Let's move on to a little talk about "Roots."

How did "Roots" come about, or how did you first hear about it?

Or did you know Alex Haley, how did that come about?

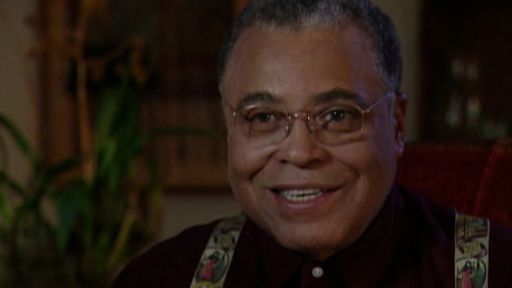

- Well, it came about, fortunately, the way I came into "Roots," I was fortunate enough to be on that list of actors who should be in "Roots," and I wanted to play Kunta Kinte's father, and then I wanted to be somebody more important, and James Earl Jones, how come?

You know, we fought about who we wanted to be in "Roots."

It was so important for us.

I got the part I was supposed to have gotten, and Maya got the part she should have gotten, and so did Cicely, and so did LaVar, and so did James Earl, and JD.

All those people got the parts they were supposed to have, including OJ Simpson.

He was the one that was running.

(laughing) But we had got the parts we're supposed to go.

Some clever divine intervention got us the right parts.

Alex Haley grew outta that merchant Marine vessel that he wrote this thing, and it exploded on him.

It happened bigger than anybody would expect.

But here we are about to express ourselves after all this time, and then I remember the people in the television network saying, "Oh, we're gonna lose some money on this one.

Oh, why, I've got this contract with David Wolper.

Oh, he's a troublemaker, but I respect him.

Well, let's put it on one day at a time and get rid of it."

And that's how "Roots" started, and you see what happened.

The stuff that we knew all along, some of us did not, and we used to talk about it in the rooms and kitchens with one another, at churches, now it's global, and the reception was outstanding, obviously.

And it's nice to be part of that family, that legacy of "Roots."

Now even today we're kind of a piggybacking on that legacy of "Roots."

- [Interviewer] Can you talk a little deeper about that?

Because when "Roots" came out, it had an extraordinary impact on our culture, both for whites and Blacks, so it seems like few shows in American television have had that kind of impact.

Can you talk about that, what impact did "Roots" have?

- Well, the impact that "Roots" had on not just America but the world, it's a story that nobody really knew how real slavery was and how slavery came about.

There's still more to talk about, but that story about doing the research and bringing those people from Africa in the Middle Passage and putting them in slavery to create an industry and help America in the South, the specific visceral relationships that was covered, at that time, quite dramatically, was a revelation, 'cause you could read about it a little bit in the chapter in the history book.

You can't get the feeling of how it really was.

You can hear some songs, you can read the slave songs.

I used to sing folk music and all the slave songs and about how hard it was.

I got stories from my great-grandmother who was a slave, and it wasn't all bad, but it was horrible, but not all bad because they got used to it.

It was the revelation that we knew basically what happened, 'cause we hear stories, but the world didn't really realize the horrific stories that happened during those hundreds of years, and how it happened and what happened, specifically through Kunta Kinte.

So now everybody knows, and we thought that was gonna be over, and that was it.

And the world responded, it shut the world down, and they would still watch it.

If they put it out, they'd watch it again.

Of course, we've got "12 Years a Slave" and other things happening now.

"Selma," all that stuff is getting quite important.

We're gonna get to that place, we're getting to an even level so we can go talk about the other stories about us as a people, about our Harlem Renaissance, which Maya talked a great deal about, and the great people there, and the great cowboys, the soldiers, and there's a bigger story.

"Roots" is not finished.

I think it had, "Roots" had an effect.

It did create a great deal of dialogue on all levels.

I didn't realize it made a lot of friends, made a lot of enemies, but it was up above the table, as it is today.

Everything is above the table, thank goodness for the computer and the internet.

There's no secrets now, so the subject is still being discussed obviously today.

And as soon as we get finished with that, then we get rid of all of those poisons, we can get on with this global community that we need to have.

But once again, Maya was in the middle, along with the James Baldwins and people like that, opening up those stories in such an eloquent way to help us grow with the information that we need to have about how horrible slavery is anywhere.

"Holocaust" did that, "Roots" started that, and it's still not over, as you can see with the productions today, and we're still on the promised land on the way toward it, a little faster than we've realized, because things are coming to a head.

But back in those days, it was supposed to be taboo to speak like that, and we did it on international television, it's history.

- [Interviewer] Can you describe, I know you weren't in the segment that Maya is in, 'cause she plays Kunta Kinte's grandmother, and you were Fiddler later on in the series, but can you just describe to us what her role was and what you thought of her performance?

- Oh, when I thought of Maya's performance, I don't think she said she had thought about it.

She just did that role.

She had all the information in her system, as Cicely had.

It was one of the consummate expression of her art and of her soul, in "Roots" especially, 'cause it was a triumphant part to play Mother Africa.

She was the mother, the grandma, she was the one, she was the matriarch, and she relished in that role, and she still relishes even today, even though she might physically be gone, she's relishing as the matriarch, the poet laureate of us.

Her statements ring so true.

You can read a poem or read a moment about hers, and occasions come up on a daily basis, when you talk about it, that's the first time I heard about it came from Maya.

And the first time I heard Maya talk like that was 1962, so it's her legacy has gotten quite strong.

She was like my great-grandmother.

She was very cantankerous.

"You don't put that much salt in the corn bread."

I mean, where did the poet laureate, where'd she go?

"Just a minute," you know?

"Lemme show you how to mix this."

I said, "Maya?"

But that's, she was imbued with our roots, that's who she is, and so she had lost patience, but not so negatively so, she just fussed a lot, and my great-grandmother fussed a lot, you know?

I have this story about my great-grandmother, which, and Maya at her later years was kind of guilty of the same forgetfulness.

And one day my great-grandmother and her two friends were over 80 years old.

My great-grandmother died at 120, approximately, more or less, but she was the mother of the first Baptist Church of Sheepshead Bay, and I was sitting in the kitchen drinking coffee, and one of the ladies said, "I think I'm getting a little senile, because I went to get something outta the refrigerator, and I stood there with the door open for five minutes trying to remember what I wanted to get out of the refrigerator."

And then the second lady says, "You know, I know what you mean 'cause I stood in my closet for 20 minutes, what am I doing standing in the closet?"

And my great-grandmother said, a la Maya Angelou, "You should be ashamed of yourself talking about how old and senile you're getting.

I'm at least 10 years older than both of you, and (knocking on wood) thank God- Who is it?"

(all laughing) - [Interviewer] That's great.

- Maya was like that during her latter years, 'cause she was very cantankerous.

"How many times did I tell you to bring me some milk, and you bring me some buttermilk?"

She asked for buttermilk in the first place.

But when it came to talking about African roots and her legacy, clarity came to her.

So the day she died, she was clear as a bell about her job in life, and transforming her information over, her knowledge to somebody else.

That's amazing process about what we have as a legacy.

I guess other people have it, but we could be senile, we could be nervous, but when it comes to that important message, clarity hits, and Maya was that way until she left our planet.

- [Interviewer] This is a tough question, but I just want to know, when you first found out that Maya had passed at the end of May, what went through your mind, when did you first hear it?

- When I heard that Maya passed, everything is quiet as it was just now.

I got quiet in my system, and to stop and reflect on all the experiences that I've had with her.

I was in this room, and there was a great silence about.

Everything stopped, and the memories of her, all of them came to pass.

She said yes to my foundation.

My foundation's called the Eracism Foundation.

She was gonna be the first board of directors, so there's a lot of lessons that she told us, "Here's what the foundation should be about."

So I was very grateful that I had her to lead me to others, and she was leading me to others, and I had a lot of weekly telephone conversations with her, and I did her show, went to her house, and we emailed a lot of one another, and she said, "What's going on?"

You know, she pushed me a lot, and gave me some lessons about what direction, and those lessons are the lessons that we used to give from one generation to the next, maybe three or four generations ago.

That's the inspection before our hand touched the doorknob, certain things that we were taught by our elders, our hygiene, our self-respect, our respect for the opposite sex, our respect for the elders, knowledge of our culture, conflict resolution, physical fitness, spirituality, before our hand touched the doorknob, and then when we went out there, we were protected a little bit, and going to school with that mindset.

Conflict resolution, so somebody who does not look or feel or believe in us, we could get along, so that when those kids went to a school to learn, they were there receptive to learn, and do positive things with it rather than negative things.

We used to do that naturally, starting in Africa.

There was something to do with each generation, and she reminded me of that, a lot of us, that we have to go back to those, she called 'em thrilling days of yesteryear, where as soon as you're able to walk, there was something you did to benefit the whole tribe.

At three years old, you'd go and gather eggs, and the eggs, everybody would eat, milk a goat, and everybody would have the goat's milk.

And at five or six, there was something else you would do, and take, herd the goats and stuff, and at 15 you, you know, every age there was something to do.

And we began to lose that as we got into integration, and she got a little more upset as we started losing those basics.

The ability to cook a sweet potato pie properly, the ability to pray, and the ability to read about your people, and then to grow on a daily basis, started back in Africa, and maintained us all through slavery.

And as we started to become equal, we abandoned the wrong things.

And she brought us as a reminder that perhaps in our freedom, we have to go back to those roots, and add that to the whole melting pot of America, indeed, the world.

Those are her words, and that's her everyday action.

We have something to offer society, and it's positive, not negative, and there's some kind of resistance to it, but in spite of all of that, it's probably one of the salvations of mankind, those original African roots that went through the Middle Passage, through slavery, through recovery, and now with that freedom, with Maya and Dr. King, there's some value systems that are indelible, that survived all of this time that's more relevant for the salvation of us all today.