Journalist and former professional dancer Juan Michael Porter II shares an intimate perspective on Alvin Ailey’s transformative career, finding inspiration in Ailey’s hidden battle with AIDS.

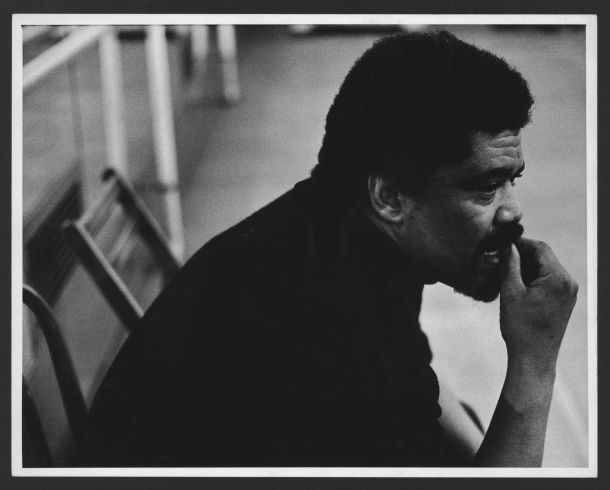

Alvin Ailey is internationally hailed as a choreographic genius. Looking at his Black-culture-rich masterpieces, it is easy to understand why.

Long before it was popular to tweet #BlackLivesMatter, he was embodying this truth through his transcendent fusion of dance, theatrical narratives, and music. Alvin Ailey, Jr. may have been born in the virulently racist countryside of 1931’s Texas, but he grew up to create an institution where Black lives were treasured and people of all backgrounds were welcome to step into their greatness.

Ailey’s accomplishments are particularly remarkable when one remembers that there was no precedent for them. In addition to growing up impoverished and without possibility models, during his childhood, most radio stations outright refused to play songs recorded by Black artists. Let’s not forget that the only roles available to Black theater, film and television actors at the time were servile or laden with repugnant tropes.

Rather than accept white supremacy’s lock on American culture, Ailey fought for and developed his own vision of what life could be. In addition to near-universal acclaim, his many accolades included receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship, Kennedy Center Honor, NAACP Spingarn Medal, United Nations Peace Medal, and after his death, having Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater designated as the United States’ cultural ambassador to the world.

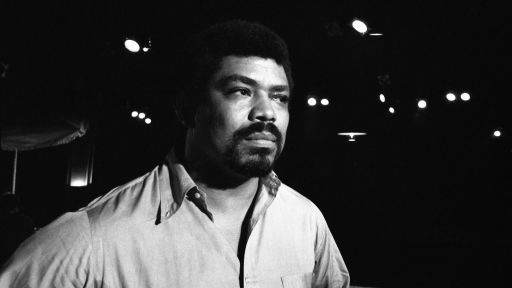

But beyond the glamor of his charisma and success, few people know who Ailey really was. The tragedy there is that this secrecy likely led to his death at the age of 58. Indeed, when Ailey died from AIDS-related complications on December 1, 1989, he left a request that his doctor announce that terminal blood dyscrasia was the cause in order to spare his mother from the shame of being associated with AIDS.

I think it is fair to say that the only shame was that the world led him to believe that he had any reason to feel ashamed and that he was too afraid to fight for his life with the same passion that he devoted to uplifting his people.

I am eternally indebted to Ailey for showing me that it was possible for a Black kid from Alabama to bare his soul through movement to audiences across the globe and to create my own path when what was available did not suit my tastes. But as a Black gay man living with HIV, I am haunted by the sad irony that the day he died on is known as World AIDS Day; a day that was created to support people with HIV or AIDS and to commemorate those who have died due to the virus.

In recent years, December 1st has become a clarion reminder that it is possible to thrive while living with this condition. But back in 1989, when World AIDS Day had just crossed its first year celebration, HIV and AIDS were still considered death sentences and people who were diagnosed with the virus were treated like pariahs.

Case in point, according to a national poll of 2,308 adults conducted by L.A. Times in 1985, 51% of respondents supported quarantining AIDS patients and making it illegal for them to have sex with another person. In 1988, a poll of 4000 doctors conducted by Boston Globe found that “15% would refuse to treat a patient with AIDS and that half thought they had a right to do so.” When results from another poll by L.A. Times were reported in 1989, four and a half months before Ailey’s death , 42% of 3,583 respondents stated that they favored suspending “some civil liberties” to fight AIDS, and 60% favored mandatory testing for “high-risk individuals,” such as homosexual men. Meanwhile, according to the The New York Times, a national poll of 5,800 dentists from that same year found that only 31% reported that they were willing to treat AIDS patients.

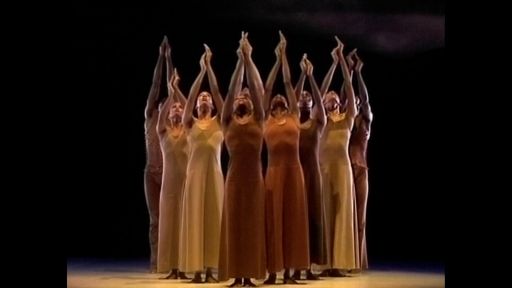

Ailey loved his people regardless of who they were. And yet he lived and died during a time when he was forced to hide his very existence. When we consider the magnificent stories that he sculpted into life―Black laborers airing their raucous delights before heading off to church in “Blues Suite,” the revolt against South African apartheid and Chicago’s racial violence in “Masekela Langage,” “Cry’s” ode to Black women everywhere, especially our mothers: the soulfully sensuous send-off to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in “Three Black Kings,” and “Memoria’s” journey through pain into spiritual release―it feels wrong not to embrace all that he was.

Especially when one realizes that 32 years after his death, his work still provides the world with its greatest depictions of Black people in all of their complicated beauty. Sadly, though Ailey’s life-affirming creations continue to elevate so many of us, the very things that led to his death―HIV, AIDS and stigma―are still ruining lives.

This is particularly true for Black people who remain disproportionately impacted by HIV and AIDS. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) most recent data, though Black people only account for 13% of the overall population in this country, Black men represented 39% of all diagnoses, while Black women accounted for 57%. The reasons why have everything to do with HIV stigma which prevents people from accessing preventative and life-saving care. But it does not have to be this way.

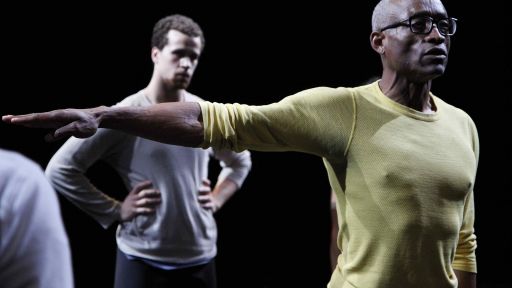

Over the past year, I have spoken with a number of Ailey’s former dancers―Dwight Rhoden, Desmond Richardson and Professor Carl Paris. Though they are not living with HIV, they have all dedicated themselves to celebrating Ailey by rejecting status based stigma and encouraging the people they work with to embrace who they are.

By doing so, they are creating a world where Ailey might have felt safe to love himself and others openly―a world where he might have lived to enjoy his 91st birthday. Much like Rhoden, Richardson and Paris, I am making a point to hold space for every aspect of who Ailey was. Especially the parts that frightened him. Not only because it is the right thing to do, but because it’s likely that they fueled him to create dances where people like me are free to live as openly as he couldn’t.