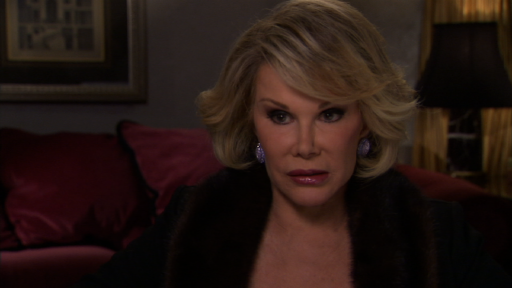

American Masters sat down with Finding Lucy director Pamela Mason Wagner and writer Thomas Wagner to get some of their thoughts on Lucille Ball, and what is was like making a film about one of America’s best loved comediennes.

Q: Why Lucy?

Pamela Mason Wagner: A lot of people have asked us what drew us to Lucille Ball as a subject. Executive producer Susan Lacy had wanted to make a film about Ball for a long time, recognizing both her genius as a performer and also the ground breaking nature of her work.

Pamela Mason Wagner: A lot of people have asked us what drew us to Lucille Ball as a subject. Executive producer Susan Lacy had wanted to make a film about Ball for a long time, recognizing both her genius as a performer and also the ground breaking nature of her work.

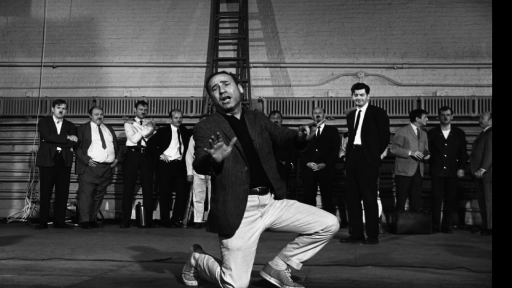

Thomas Wagner: Lucy, and Desi also, really changed the business of television in a radical and fundamental way. She and her collaborators, in the process of simply trying to get the work in front of an audience, invented the television situation comedy. And we have been looking at it through their lens for fifty years. It’s that kind of fundamental influence that makes her an American Master.

PMW: I was intrigued by Lucille Ball because she’s full of contradictions, which is always fodder for a good story. She was a funny actress who couldn’t tell a joke, and was quite serious in real life. She became one of the most successful business women in Hollywood, yet she was never comfortable with her own power. So, when Susan asked us to make the film, we were excited but also a little worried.

TW: Believe me, no one wants to take on the life of the most beloved character in 50 years of television and blow it. I wasn’t particularly a Lucy fan when we started our research. I was much more oriented toward early television programs like “The Twilight Zone.” Situation comedy never had the same appeal to me. But after looking at her work, seeing a lot of it over a compressed time period, well, it’s really quite amazing. For one thing, she is extraordinarily consistent in her portrayal of that character. In fact consistency was a hallmark of the entire series. The writing, the production values, the performances — it’s just remarkable.

PMW: Our entire production team pitched in, gladly, to watch the 180 “I Love Lucy” programs. And we had lively discussions about which moments were the funniest.

TW: Dina Hossain, our co-producer, is from Bangladesh, and did not grow up watching “I Love Lucy,” so she brought a unique perspective and came to the material fresh. Pam and I watched most of the episodes at home with our (then) 7 year old daughter, Emily. Ultimately, she turned out to be our best judge. She had no preconceptions about what was classic or anything else. But, invariably, she was completely tuned in to the really funny moments.

PMW: She has internalized the character so completely that when something crazy happens in our real lives she sometimes says, “Mama, this is like a Lucy episode.”

TW: Among other things, she taught us that Lucy doesn’t really date. Those magic moments that were funny 50 years ago, are still just as funny now.

Q: From the enormous amount of Lucy footage, how did you chose clips for the film?

PMW: People often want to know how we picked the performance material, how we winnowed all that footage down and decided what to include in the documentary. Well, first, it is important to point out that with CBS as our co-production partner, we had unique access to the “I Love Lucy” programs.

TW: That material, so important, so central to Lucy’s story, is normally extremely expensive and without the wonderful deal struck by executive producer Susan Lacy, it would have been prohibitive to use clips from “I Love Lucy” as extensively as we have done.

PMW: In addition to searching for classic bits, we were on the lookout for forgotten episodes, shows that haven’t been distributed in the home video market, but that hold up, and even shine. We were also watching for episodes whose themes are echoed in the documentary: shows about the importance of family, about the battle of the sexes, about Lucy Ricardo’s desire to be more than just a housewife.

TW: Exactly! From the start, we knew that in order to be more than a very entertaining clip program, we would have to find a new way to view her show — a way to connect her real life with the groundbreaking work she is known for. In some cases we were just lucky. We knew one episode we wanted to include (because it so beautifully demonstrates her hunger to be in show business) was “The Dancing Star” with Van Johnson. We interviewed Van and it turned out he didn’t remember a lot of detail about that particular experience. But a few days later, we spoke to Fran Drescher, the star of “The Nanny.” We wanted to interview a younger comedienne for whom Lucy is a major role model and inspiration.

PMW: And as we spoke, out of the blue, she expressed her love for this episode with Van Johnson; how it was such an influence on her and how it made her want to be an actress.

TW: And she remembered the episode in such sharp detail! It clearly made a deep impression on her. It really is a wonderful moment.

PMW: Finally, we had to find moments from “I Love Lucy” that worked well together. Our editor, Nancy Roach, tried an infinite number of combinations when cutting together funny bits from different episodes. At first glance, it seems like “how can you go wrong with all this great material, it must be a piece of cake to make it work.” That proved far from true: in fact, Nancy found it necessary to build between the clips, sometimes starting with a quietly funny moment, then leading up to an uproarious one. And we discovered, you can only take so much at one time, and then it stops being funny. Rhythm and pacing are everything.

TW: The Superman episode is a perfect example. We tried that scene with Lucy on the ledge in the rain about to be rescued by Superman, in a number of different places. On its own, it’s hilarious. But every time we cut it together with other scenes, it stopped working.

PMW: After a long while we discovered the place where it finally ended up in the movie. And as luck (and good editing) would have it, it not only caps a sequence about guest stars on “I Love Lucy”’ it provides a needed transition to a discussion of the Arnaz marriage versus the Ricardos’ marriage.

TW: In the end we used the film clips to tell the larger story of a life, which is, I think, what distinguishes American Masters from celebratory “clip shows” that string together everybody’s favorite moments. An American Masters documentary has to create another layer of storytelling, that gets at the more subtle and compelling aspects of a person’s life.

Q: Tell us about the documentary’s structure.

PMW: People have commented on the placement of Lucy’s childhood in the chronology of the film (it comes in Act III). We laugh and say our goal as filmmakers is to someday get the childhood into the fourth act. Kidding aside, the challenge we believe, is not to just begin at the beginning, which is, of course, what is expected, often, of an historical biographical film. We spent a long time thinking about how Lucy’s childhood should come out of something in her adult life, as an answer to a question. So her childhood became a response to our discussion of her adult family life, when she is a mother of two young children and is juggling that with her career.

TW: Early in the process, it’s just impossible to know how the various parts of someones story are going to play. I’m glad we were able to hold off on her childhood until late, because now it really has impact. Once we get to know Lucy, see her vulnerabilities in play, the losses and sadnesses of her early life suddenly resonate. And like a lot of people in comedy, her childhood was not a safe, happy runway from which to launch her life. She was always very quick to point out that the “hard knocks” of her childhood never really harmed her — but she comes from a generation not overly inclined to introspection or self-reflection.

PMW: It’s interesting though, that this brilliant performer, whose childhood was torn apart by death and loss, worked so hard to reunite her biological family as an adult, inviting practically all of her relatives to come live with her in Hollywood.

TW: And we were intrigued at how she and Desi, who also had a childhood cut short (by revolution in Cuba), tried to create a large, extended family in their worklife and at their company, Desilu.

Q: Tell us about the music for the film.

TW: I’ve been asked about what it was like to serve as both writer and composer on a film. In truth, it is a mixed blessing. I wore the same two hats on the American Masters film about Rod Serling and found out the pitfalls as well as the rewards. The downside is that the schedule can be crushing, especially in the endgame — delivering final score and doing last rewrites on the script had it’s daunting moments. On the other hand, words and music share such an emotional connection, creating both gives you a unique opportunity to make the most of that relationship.

As for the “I Love Lucy” theme — in the past, it never struck me as particularly noteworthy. The original arrangement is a kind of curious mix of Latin percussion and mainstream television orchestra. But the theme turned out to be quite muscular — and flexible. It stood up to lots of different treatments, providing score for some very emotional moments in the film including the sequence surrounding the end of their marriage. It worked as a waltz, as a zippy pizzicato accompaniment to Lucy’s success story, as a kind of funeral march. It even works as the tense underpinning for the section of the film that deals with Lucy’s brush with the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was great fun to see how many places I could take it.

Q: What was it like making a film for American Masters?

PMW: In the end, all documentary filmmakers have essentially the same elements to work with to tell their story: interviews with people who knew their subject; photographs; footage of their subject; letters, audio interviews, music. What I like about American Masters is that there is no formula that must be adhered to. There’s no rule book about how those elements are to be combined.

TW: Each films’ aesthetic– its structure, how it looks, its pacing and rhythms– emerges organically from the subject matter. Our film’s nostalgic tugging at the heart strings tone might not be appropriate for next month’s American Master. But that didn’t mean we couldn’t go in that direction if it fit our subject.

PMW: It’s why I like watching American Masters programs, because I’m always in for a surprise, something unexpected. And it’s why I liked making one — we were encouraged to make a complex film about a complex lady — not just a laugh riot about a very funny actress. And in a way, I’m most proud of the sad moments in the film. Because they’re not what you expect in a film about Lucille Ball.