Republished with permission from The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

“Red” Upshaw (pictured fifth from left) and Margaret Mitchell’s (pictured sixth from left) wedding photo, September 2, 1922. Upshaw is believed to be the model for the Rhett Butler character in Gone With the Wind. Best man John Marsh (pictured second from left) would become Mitchell’s second husband, July 4, 1925, and her editor when writing Gone With the Wind. Also pictured, Mitchell’s older brother Stephens (far right). Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

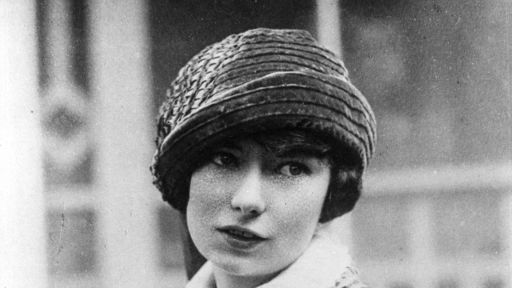

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell was born on November 8, 1900, in Atlanta. Her great-great-great-grandfather Thomas Mitchell fought in the American Revolution (1775-83), and his son William Mitchell took part in the War of 1812. Her great-grandfather Isaac Green Mitchell was a circuit-riding Methodist minister who settled in Marthasville, which later was named Atlanta. Mitchell was thus a fourth-generation Atlantan. Her grandfather Russell Mitchell fought in the Civil War and suffered two bullet wounds to the head during the fighting at Antietam. Twice married, he had twelve children, the oldest of whom was Mitchell’s father, Eugene.

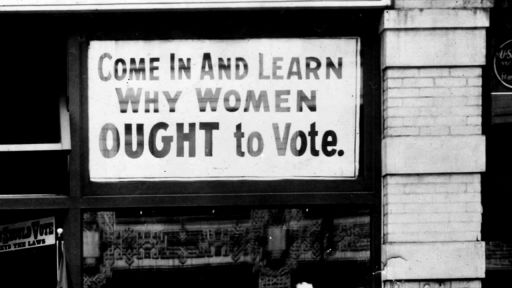

Mitchell’s mother’s family was Irish Catholic. Her great-grandfather Phillip Fitzgerald came to America from Ireland and eventually settled on a plantation near Jonesboro in Fayette County. (This portion of the county now lies in Clayton County.) The Fitzgeralds had seven daughters. Annie Fitzgerald, Mitchell’s grandmother, married John Stephens, who had emigrated from Ireland and settled in Atlanta. Stephens amassed large real-estate properties and helped found a trolley-car system in the city. The Stephenses had twelve children; Mary Isobel (May Belle), Mitchell’s mother, was the seventh. May Belle married Eugene Muse Mitchell on November 8, 1892. Eugene was a noted Atlanta attorney, and May Belle was a staunch supporter of woman suffrage. They had a son, Stephens, followed four years later by a daughter, Margaret Munnerlyn.

Mitchell began making up stories before she could write, dictating them to her mother. Later she made her own books with cardboard covers and filled them with adventure stories using her friends, relatives, and herself as characters. As she grew older she switched to copybooks, which her mother stored in inexpensive enamel bread boxes. A few of the hundreds of tales that she wrote have survived, including two Civil War tales. When the family moved to Peachtree Street, the young Mitchell attended the Tenth Street School and later Woodberry School, a private school. She branched out to writing, directing, and starring in plays, coercing the neighborhood children to take part.

From 1914 to 1918 Mitchell attended the Washington Seminary, a prestigious Atlanta finishing school, where she was a founding member and officer of the drama club. She was also the literary editor of Facts and Fancies, the high school yearbook, in which two of her stories were featured. She was president of the Washington Literary Society.

When America entered World War I (1917-18), the seminary girls were in demand at dances for the young servicemen stationed at Camp Gordon and Fort McPherson. At one such dance in the summer of 1918 Mitchell met twenty-two-year-old Clifford Henry, a wealthy and socially prominent New Yorker who was a bayonet instructor at Camp Gordon. The two fell in love and became engaged shortly before he was shipped overseas. He was killed in October 1918 while fighting in France.

In September 1918 Mitchell entered Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she began using the nickname “Peggy.” Her freshman year at college was disrupted when an influenza epidemic forced the cancellation of classes. In January her mother contracted influenza and died the day before her daughter reached home. Mitchell completed her freshman year at Smith, then returned to Atlanta to take her place as mistress of the household and to enter the upcoming debutante season. During the last charity ball of the season, Mitchell created a scandal by performing a sensuous dance popular in the nightclubs of Paris, France.

Soon Mitchell met Berrien Kinnard Upshaw, who was from a prominent Raleigh, North Carolina, family. They were wed in 1922, but the marriage was brief. After four months Upshaw left Atlanta for the Midwest and never returned. The marriage was annulled two years later.

In the same year that she married, Mitchell landed a job with the Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine. She used “Peggy Mitchell” as her byline. Her interviews, profiles, and sketches of life in Georgia were well received. During her four years with the Sunday Magazine, Mitchell wrote 129 articles, worked as a proofreader, substituted for the advice columnist, reviewed books, and occasionally did hard news stories for the paper. Complications from a broken ankle led her to end her career as a journalist.

Mitchell’s second marriage was to John Robert Marsh on July 4, 1925, and the couple set up housekeeping in a small apartment affectionately called “the Dump.” They entertained the newspaper crowd and other friends on a regular basis. Marsh, originally from Maysville, Kentucky, worked for the Georgia Railway and Power Company (later Georgia Power Company) as director of the publicity department.

In 1926, to relieve the boredom of being cooped up with a broken ankle, Mitchell began to write Gone With the Wind. Setting up her Remington typewriter on an old sewing table, she completed the majority of the book in three years. She wrote the last chapter first and the other chapters in no particular order. Stuffing the chapters into manila envelopes, she eventually accumulated almost seventy chapters. When visitors appeared, she covered her work with a towel, keeping her novel a secret. There has been much speculation on whether the characters were based on real people, but Mitchell claimed they were her own creations.

In April 1935 Harold Latham, an editor for the Macmillan publishing company in New York City, toured the South looking for new manuscripts. Latham heard that Mitchell had been working on a manuscript and asked her if he could see it, but she denied having one. When a friend commented that Mitchell was not serious enough to write a novel, Mitchell gathered up many of the envelopes and took them to Latham at his hotel. He had to purchase a suitcase to carry them. He read part of the manuscript on the train to New Orleans, Louisiana, and sent it straight to New York. By July Macmillan had offered her a contract. She received a $500 advance and 10 percent of the royalties.

As she revised the manuscript, Mitchell cut and rearranged chapters, confirmed details, wrote the first chapter, changed the name of the main character (originally called Pansy), and struggled to think of a title that suited her. Titles considered included Tomorrow Is Another Day, Another Day, Tote the Weary Load, Milestones, Ba! Ba! Blacksheep, Not in Our Stars, and Bugles Sang True. Finally she settled on a phrase from a favorite poem “I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind, / Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng.” Published in 1936, Gone With the Wind was 1,037 pages long and sold for three dollars.

Gone With the Wind was a phenomenal success and received rave reviews. Overnight, Mitchell became a celebrity and remained very much in the public spotlight through the production and premiere of the film based on her novel in 1939. She was in constant demand for speaking engagements and interviews. At first she complied, but later, pleading poor health, she usually declined these requests and stopped autographing copies of her book. She said she wanted to remain simply Mrs. John Marsh.

Gone With the Wind was Mitchell’s only published novel. At her request, the original manuscript (except for a few pages retained to validate her authorship) and all other writings were destroyed. These included a novella in the Gothic style, a ghost story set in an old plantation home left vacant after the Civil War. According to the recollections of Lois Cole, a friend of Mitchell’s and a Macmillan employee, three people had read this tale (written before Gone With the Wind) and thought it was worth publishing by one of the bigger publishing houses. Cole suggested that Mitchell enter it in the Little, Brown novelette contest.

Possibly one of the reasons that Mitchell never wrote another novel was that she spent so much time working with her brother and her husband to protect the copyright of her book abroad. Up until the publication of Gone With the Wind, international copyright laws were ambiguous and varied from country to country. Correspondence also took much of her time. During the years following publication, she personally answered every letter she received about her book. With the outbreak of World War II (1941-45), she worked tirelessly for the American Red Cross, even outfitting a hospital ship. She also set up scholarships for black medical students.

August 11, 1949, Mitchell and her husband decided to go to a movie, A Canterbury Tale, at the Peachtree Art Theatre. Just as they started to cross Peachtree Street, near 13th Street, a speeding taxi crested the hill. Mitchell stepped back; Marsh stepped forward. The driver applied the brakes, skidded, and hit Mitchell. She was rushed to Grady Hospital but never regained consciousness. During the five days before she died, crowds waited outside for news. U.S. president Harry Truman, Georgia governor Herman Talmadge, and Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield all asked to be kept informed of her condition. Special phone lines were installed at Grady Hospital, and friends manned the lines in four-hour shifts. Mitchell died on August 16, 1949, and was buried in Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta.

Mitchell was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement in 1994 and into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2000.