The Woman Who Will Not Die

By Gloria Steinem, 1986

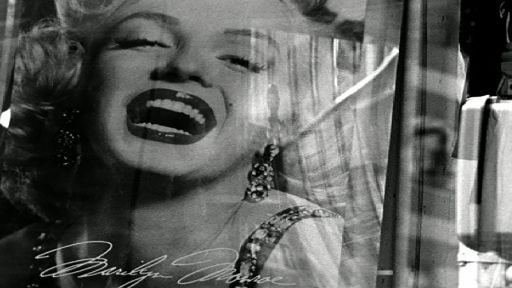

It has been nearly a quarter of a century since the death of a minor American actress named Marilyn Monroe. There is no reason for her to be a part of my consciousness as I walk down a midtown New York street frilled with color and action and life.

In a shop window display of white summer dresses, I see several huge photographs – a life-size cutout of Marilyn standing in a white halter dress, some close-ups of her vulnerable, please-love-me smile – but they don’t look dated. Oddly, Marilyn seems to be just as much a part of this street scene as the neighboring images of models who could now be her daughters – even her granddaughters. I walk another block and pass a record store featuring the hit albums of a rock star named Madonna. She has imitated Marilyn Monroe’s hair, style, and clothes, but subtracted her vulnerability. Instead of using seduction to offer men whatever they want, Madonna uses it to get what she wants – a 1980’s difference that has made her the idol of teenage girls. Nevertheless, her international symbols of femaleness are pure Marilyn.

A few doors away, a bookstore displays two volumes on Marilyn Monroe in its well-stocked window. The first is nothing but random photographs, one of many such collections that have been published over the years. The second is one of several recent exposes on the circumstances surrounding Monroe’s 1962 death from an accidental or purposeful overdose of sleeping pills. Could organized crime, Jimmy Hoffa in particular, have planned to use her friendship with the Kennedys and her suicide – could Hoffa and his friends even have caused that suicide – in order to embarrass or blackmail Robert Kennedy, who was definitely a mafia enemy and probably her lover? Only a few months ago, Marilyn Monroe’s name made international headlines again when a British television documentary on this conspiracy theory was shown and a network documentary made in the United States was suppressed, with potential pressure from crime-controlled unions or the late Robert Kennedy’s family as rumored reasons.

I knew I belonged to the public and to the world, not because I was talented or even beautiful but because I had never belonged to anything or anyone else.

—From the Unfinished Biography of Marilyn Monroe

As I turn the corner into my neighborhood, I pass a newsstand where the face of one more young Marilyn Monroe look-alike stares up at me from a glossy magazine cover. She is Kate Mailer, Norman Mailer’s daughter, who was born the year that Marilyn Monroe died. Now she is starring in “Strawhead,” a “memory play” about Monroe written by Norman Mailer, who is so obsessed with this long-dead sex goddess that he had written one long biography and another work – half fact, half fiction – about her, even before casting his daughter in this part.

The next morning, I turn on the television and see a promotion for a show on film director Billy Wilder. The only clip chosen to attract viewers and represent Wilder’s entire career is one of Marilyn Monroe singing a few breathless bars in Some Like It Hot, one of two films they made together.

These are everyday signs of a unique longevity. If you add her years of movie stardom to the years since her death, Marilyn Monroe has been a part of our lives and imaginations for nearly four decades. That’s a very long time for one celebrity to survive in a throwaway culture.

In the 1930’s, when English critic Cyril Connolly proposed a definition of posterity to measure whether a writer’s work had stood the test of time, he suggested that posterity should be limited to 10 years. The form and content of popular culture were changing too fast, he explained, to make any artist accountable for more than a decade.

Since then, the pace of change has been accelerated even more. Everything from the communications revolution to multinational entertainment has altered the form of culture. Its content has been transformed by civil rights, feminism, an end to film censorship, and much more. Nonetheless, Monroe’s personal and intimate ability to inhabit our fantasies has gone right on. As I write this, she is still better known than most living movie stars, most world leaders, and most television personalities. The surprise is that she rarely has been taken seriously enough fur us to ask why that is so.

One simple reason for her life story’s endurance is the premature end of it. Personalities and narratives projected onto the screen of our imaginations are far more haunting – and far more likely to be the stuff of conspiracies and conjuncture – if they have not been allowed to play themselves out to their logical or illogical ends. James Dean’s brief life is the subject of a cult, but the completed lives of such “outsiders” as Gary Cooper or Henry Fonda are not. Each day in the brief Camelot of John Kennedy inspires as much speculation as each year in the long New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt. The few years of Charlie “Bird” Parker’s music inspire graffiti (“Bird Lives”), but the many musical years of Duke Ellington do not.

When the past dies there is mourning, but when the future dies, our imaginations are compelled to carry it on.

Would Marilyn Monroe have become the serious actress she aspired to be? Could she have survived the transition from sex goddess to mortal woman that aging would impose? Could she had stopped her disastrous marriages to men whose images she wanted to absorb (Beloved American DiMaggio, Serious Intellectual Miller), and found a partner who loved and understood her as she really was? Could she have kicked the life-wasting habits of addiction and procrastination? Would she have had or adopted children? Found support in the growing strength of women or been threatened by it? Entered the world of learning or continued to be ridiculed for trying? Survived and even enjoyed the age of 60 she now would be?

Most important, would she finally have escaped her lifetime combination of two parts talent, one part victim, and one part joke? Would she have been “taken seriously,” as she so badly wanted to be?

We will never know. Every question is as haunting as any of its possible answers.

But the poignancy of this incompleteness is not enough to explain Marilyn Monroe’s enduring power. Even among brief public lives, few become parables. Those that endure seem to hook into our deepest emotions of hope or fear, dream or nightmare, of what our own fates might be. Successful leaders also fall into one group or the other: those who invoke a threatening future and promise disaster unless we obey, and those who conjure up a hopeful future and promise reward if we will follow. It’s this power of either fear or hope that makes a personal legend survive, from the fearsome extreme of Adolph Hitler (Did he really escape? Might he have lived on in the jungles of South America?) to the hopeful myth of Zapata waiting in the hills of Mexico to rescue his people. The same is true for the enduring fictions of popular culture, from the frightening villain to the hopeful hero, each of whom is reincarnated again and again.

In an intimate way during her brief life, Marilyn Monroe hooked into both those extremes of emotion. She personified many of the secret hopes of men and many secret fears of women.

To men, wrote Norman Mailer, her image was “gorgeous, forgiving, humorous, compliant and tender… she would ask no price.” She was the child-woman who offered pleasure without adult challenge; a lover who neither judged nor asked anything in return. Both the roles she played and her own public image embodied a masculine hope for a woman who is innocent and sensuously experienced at the same time. “In fact,” as Marilyn said toward the end of her career, “my popularity seems almost entirely a masculine phenomenon.”

Since most men have experienced female power only in their childhoods, they associate it with a time when they themselves were powerless. This will continue as long as children are raised almost totally by women, and rarely see women in authority outside the home. That’s why male adults, and some females too, experience the presence of a strong woman as a dangerous regression to a time of their own vulnerability and dependence. For men, especially, who are trained to measure manhood and maturity by their distance from the world of women, being forced back to that world for female companionship may be very threatening indeed. A compliant child-woman like Monroe solves this dilemma by offering sex WITHOUT the power of an adult woman, much less of an equal. As a child herself, she allows men to feel both conquering and protective; to be both dominating and admirable at the same time.

For women, Monroe embodies kinds of fear that were just as basic as the hope she offered men: the fear of a sexual competitor who could take away men on whom women’s identities and even livelihoods might depend; the fear of having to meet her impossible standard of always giving – and asking nothing in return; the nagging fear that we might share her feminine fate of being vulnerable, unserious, constantly in danger of becoming a victim.

Aside from her beautiful face, which women envied, she was nothing like the female stars that women moviegoers have made popular. Those stars offered at the least the illusion of being in control of their fates – and perhaps having an effect on the world. Stars of the classic “women’s movies” were actresses like Bette Davis, who made her impact by sheer force of emotion; or Katherine Hepburn, who was always intelligent and never victimized for long; or even Doris Day, who charmed the world into conforming to her own virginal standards. Their figures were admirable and neat, but without the vulnerability of the big-breasted woman in a society that regresses men and keeps them obsessed with the maternal symbols of breasts and hips. Watching Monroe was quite different: women were forced to worry for her vulnerability – and thus their own. They might feel like a black moviegoer watching a black actor play a role that was too passive, too obedient, or a Jew watching a Jewish character who was selfish and avaricious. In spite of some extra magic, some face-saving sincerity and humor, Marilyn Monroe was still close to the humiliating stereotype of a dumb blonde: depersonalized, sexual, even a joke. Yet few women yet had the self-respect to object on behalf of their sex, as one would object on behalf of a race or religion, they still might be left feeling a little humiliated – or threatened – without knowing why.

“I have always had a talent for irritating women since I was fourteen,” Marilyn wrote in her unfinished auto-biography. “Sometimes I’ve been to a party where no one spoke to me for a whole evening. The men, frightened by their wives or sweeties, would give me a wide berth. And the ladies would gang up in a corner to discuss my dangerous character.”

But all that was before her death and the revelations surrounding it. The moment she was gone, Monroe’s vulnerability was no longer just a turn-on for many men and an embarrassment for many women. It was a tragedy. Whether that final overdose was suicide or not, both men and women were forced to recognize the insecurity and private terrors that had caused her to attempt suicide several times before.

Men who had never known her wondered if their love and protection might have saved her. Women who had never known her wondered if their empathy and friendship might have done the same. For both women and men, the ghost of Marilyn came to embody a particularly powerful form of hope: the rescue fantasy. Not only did we imagine a happier ending for the parable of Marilyn Monroe’s life, but we also fantasized ourselves as saviors who could have brought it about.

Still, women didn’t seem quite as comfortable about going public with their rescue fantasies as men did. It meant admitting an identity with a woman who always had been a little embarrassing, and who had now turned out to be doomed as well. Nearly all of the journalistic eulogies that followed Monroe’s death were written by men. So are almost all of the nearly 40 books that have been published about Monroe.

Bias in the minds of editors played a role, too. Consciously or not, they seemed to assume that only male journalists should write about a sex goddess. Margaret Parton, a reporter from the Ladies’ Home Journal and one of the few women assigned to profile Marilyn during her lifetime, wrote an article that was rejected because it was too favorable. She had reported Marilyn’s ambitious hope of playing Sadie Thompson, under the guidance of Lee Strasberg, in a television version of RAIN, based on a short story by Somerset Maugham. (Sadie Thompson was “a girl who knew how to be gay, even when she was sad,” a fragile Marilyn had explained, “and that’s important – you know?”) Parton also reported her own “sense of having met a sick little canary instead of a peacock. Only when you pick it up in your hand to comfort it … beneath the sickness, the weakness and the innocence, you find a strong bone structure, and a heart beating. You RECOGNIZE sickness, and you FIND strength.”

Bruce and Beatrice Gould, editors of the Ladies’ Home Journal, told Parton she must have been “mesmerized” to write something so uncritical. “If you were a man,” Mr. Gould told her, “I’d wonder what went on that afternoon in Marilyn’s apartment.” Fred Guiles, one of Marilyn Monroe’s more fair-minded biographers, counted the suppression of this sensitive article as one proof that many editors were interested in portraying Monroe, at least in those later years, as “crazy, a home wrecker.”

Just after Monroe’s death, one of the few women to write with empathy was Diana Trilling, an author confident enough not to worry about being trivialized by association – and respected enough to get published. Trilling regretted the public’s “mockery of [Marilyn’s] wish to be educated,” and her dependence on sexual artifice that must have left “a great emptiness where a true sexuality would have supplied her with a sense of herself as a person.” She mourned Marilyn’s lack of friends, “especially women, to whose protectiveness her extreme vulnerability spoke so directly.”

“But we were the friends,” as Trilling said sadly, “of whom she knew nothing.”

In fact, the contagion of feminism that followed Monroe’s death by less than a decade may be the newest and most powerful reason for the continuing strength of her legend. As women began to be honest in public, and to discover that many of our experiences were more societal than individual, we also realized that we could benefit more by acting together than by deserting each other. We were less likely to blame or be the victim, whether Marilyn or ourselves, and more likely to rescue ourselves and each other.

In 1972, the tenth anniversary of her death and the birth year of MS., the first magazine to be published by and for women, Harriet Lyons, one of its early editors, suggested that MS. do a cover story on Marilyn called “the woman who died too soon.” As the writer of this brief essay about women’s new hope of reclaiming Marilyn, I was astounded by the response to the article. It was like tapping an underground river of interest. For instance:

Marilyn had talked about being sexually assaulted as a child, though many of her biographers had not believed her. Women wrote in to tell their similar stories. It was my first intimation of what since has become a documented statistic: one in six adult women has been sexually assaulted in childhood by a family member. The long-lasting effects – for instance, feeling one has no value except a sexual one – seemed shared by these women and Marilyn. Yet most were made to feel guilty and alone, and many were as disbelieved by the grown-ups around them as Marilyn had been.

Physicians had been more likely to prescribe sleeping pills and tranquilizers than to look for the cause of Monroe’s sleeplessness and anxiety. They had continued to do so even after she attempted suicide several times. Women responded with their own stories of being over-medicated, and of doctors who assumed women’s physical symptoms were all in their “minds.” It was my first understanding that women are more likely to be given chemical and other arm’s-length treatment, and to suffer from the assumption that they can be chemically calmed or sedated with less penalty because they are doing only “women’s work.” Then, ads in medical journals blatantly recommended tranquilizers for depressed housewives, and even now the majority of all tranquilizer prescriptions are written for women. Acting, modeling, making a living more from external appearance than from internal identity – these had been Marilyn’s lifelines out of poverty and obscurity. Other women who had suppressed their internal selves to become interchangeable “pretty girls” – and as a result were struggling with both lack of identity and terror of aging – wrote to tell their stories.

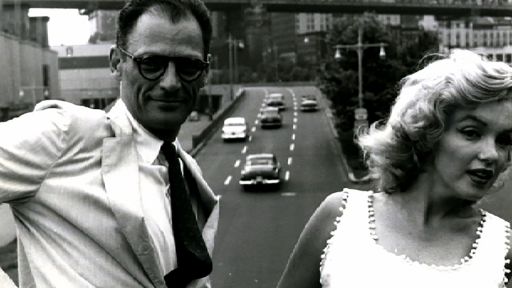

To gain the seriousness and respect that was largely denied her, and to gain the fatherly protection she had been completely denied, Marilyn married a beloved American folk hero and then a respected intellectual. Other women who had tried to marry for protection or for identity, as women are often encouraged to do, wrote to say how impossible and childlike this had been for them, and how impossible for their husbands who were expected to provide their wives’ identities. But Marilyn did not live long enough to see a time in which women sought their own identities, not just derived ones.

During her marriage to Arthur Miller, Marilyn had tried to have a child – but suffered an ectopic pregnancy, a miscarriage – and could not. Letters poured in from women who also suffered from this inability and from a definition of womanhood so tied to the accident of the physical ability to bear a child – preferably a son, as Marilyn often said, though later she also talked of a daughter – that their whole sense of self had been undermined. “Manhood means many things,” as one reader explained, “but womanhood means only one.” And where is the self-respect of a woman who wants to give birth only to a male child, someone different from herself?

Most of all, women readers mourned that Marilyn had lived in an era when there were so few ways for her to know that these experiences were shared with other women, that she was not alone.

Now women and men bring the last quarter century of change and understanding to these poignant photographs taken in the days just before her death. It makes them all the more haunting. [Editor’s Note: this chapter originally appeared with photographs, which are not present here.]

I still see the self-consciousness with which she posed for a camera. It makes me remember my own teenage discomfort at seeing her on the screen, mincing and whispering and simply hoping her way into love and approval. By holding a mirror to the exaggerated ways in which female human beings are trained to act, she could be as embarrassing – and as sad and revealing – as a female impersonator. Yet now I also see the why of it, and the woman behind the mask that her self-consciousness creates.

I still feel worried about her, just as I did then. There is something especially vulnerable about big-breasted women in this world concerned with such bodies, but unconcerned with the real person within. We may envy these women a little, yet we feel protective of them, too.

But in these photographs, the body emphasis seems more the habit of some former self. It’s her face we look at. Now that we know the end of the story, it’s the real woman we hope to find – looking out of the eyes of Marilyn.

In the last interview before her death, close to the time of these photographs, Patricia Newcomb, her friend and press secretary, remembers that Marilyn pleaded unsuccessfully with the reporter to end his article like this:

What I really want to say: That what the world really needs is a real feeling of kinship. Everybody: stars, laborers, Negroes, Jews, Arabs. We are all brothers. Please don’t make me a joke. End the interview with what I believe.