Gail Levin is an Emmy Award-winning producer/director of both television and film. Her most recent AMERICAN MASTERS production was James Dean: Sense Memories, which won a 2005 Cine Golden Eagle award. Below, she answers some questions about her latest project, AMERICAN MASTERS Marilyn Monroe: Still Life.

Q: What makes Marilyn Monroe an American Master?

A: Not only did she master her own image, create it and ultimately control it, she was the subject of many of the great masters of photography of the 20th century. This film not only depicts Marilyn, but also the very individual artists with cameras who were involved with her and with making these remarkable and sustaining images. AMERICAN MASTERS continues in its inimitable way to showcase the brilliance of its characters by finding that moment which should be forever memorialized.

Q: Marilyn Monroe was such an iconic figure, and so much of her life has already been documented. Why did you choose the photography angle for Still Life?

A: Ever since The Misfits, it’s been in my mind to do something with the photography. I’m fascinated by photography, and there exists such an incredible photographic archive since all the greats of that era photographed her so it’s more than just publicity stills and movie star pictures. And at the end of the Dean screening last year Taki Wise from the Staley-Wise Gallery came up to me and said “Are you aware that it would be Marilyn’s 80th birthday in 2006?” I thought this would be a great way to peg this idea now. I think her image is still possibly the most potent of all of them. She could, arguably, be the most photographed person of the 20th century. There were enough photographers around who could talk, and it was a great challenge and a really wonderful task to get these very intimate recollections.

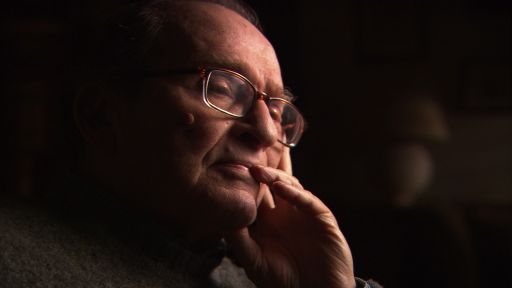

Q: You interviewed some of the great photographers of our time, including Arnold Newman, who died in June. Tell us about that interview, which may have been his last.

A: Arnold Newman was one of the great photographers of the 20th century. A great portrait photographer, the photographer of presidents, the photographer of Picasso, the photographer of Woody Allen – everybody great. Interestingly enough, he never photographed Marilyn as a portrait, even though they tried several times to set it up. He photographed her in the midst of this funny, odd grouping of people at this little party that included Carl Sandburg. It was this wonderful confluence of people: this great photographer, the great poet, the great movie star, but in a completely unexpected setting.

Newman was 88 when he died and when we interviewed him in November of last year he was very sharp, very together. I felt like we got to be friends right away. I think it was probably the last interview. The other extraordinary thing we have in this film, which is so very important to me, is the photography itself, photography itself as an idiom. The darkroom is becoming a vanishing place for photographers; the whole notion of film is going away, replaced by the digital image. And this film is framed by darkroom set ups. And one was with Newman printing a portion of this photograph that he took of Marilyn and Carl Sandburg. So I think we have Arnold Newman in his darkroom for the last time. It actually gives me a little chill, and it makes me very proud.

Q: Of the thousands of photographs you looked at for this film, which ones gave you the most insight into her true personality?

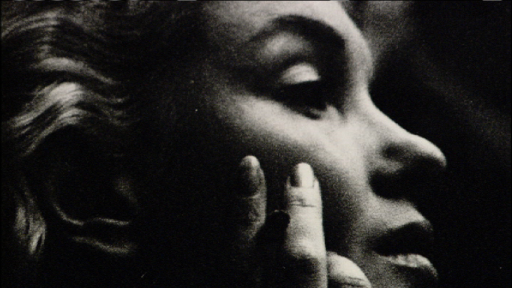

A: That one in particular, the Arnold Newman one. He says it’s the real Marilyn, you know? It really is this portrait shot of her, cut out of a two shot of her talking to Carl Sandburg. I had looked at those pictures many times, and never seen that the portrait was actually just a cropped version of this photograph. So already the eye of the photographer is present, just in being able to see what he has in his own picture. And I said to him, “God, look at that. Carl Sandburg is just listening to her,” and he said, “No, she was just pouring her heart out, she was miserable.” He did that photograph in March of ’62 and she was dead by August of ’62. She was already very troubled, very sad. So the whole circumstance of the photograph was one that you didn’t necessarily know when first looking at it.

Also, I think the opening photograph that we’ve used in the darkroom, which was taken by Roy Schatt at the Actors Studio, is a very beautiful, very open and very honest photograph of her in which you see both sides of her – the old Norma Jeane, completely without make up, with that completely open face – and Marilyn Monroe. I think it’s got incredible truth to it.

Another group of photographs I love that were quite deliberate are the black and white Ben Ross photographs. The story is that she just showed up late at night in his hotel room and he started shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting. By and large, we have a very honest group of photographs in this film. Overall, these are not the star pictures, not the glamour-puss stuff. And that was appealing to me.

Q: Unlike many of today’s stars, who have a combative relationship with the paparazzi, she seemed to embrace photographers and have a relationship with them.

A: I think she was very open, very approachable, very willing. My line about her is that she died trying. I don’t think she was closed off and a bitch and above that crowd. I think she felt she owed it to that crowd – that crowd being the audience and in a sense the paparazzi. I think that was a great joy for her, to sit with those guys, and to work with those guys. I think she thought of them as artists, and I think she thought of herself as a subject that was worthy of that. Douglas Kirkland said he thinks it’s because she had nothing to prepare for so she was very at ease. She didn’t have to remember lines. In some ways she didn’t have to worry about how she had to look for a scene, so a lot of the pressure was off her. It was a very genuine exchange.

Q: Why do you think she was so comfortable with the camera, starting with her first professional shots at 16?

A: I think she’s one of those people who figured out what she had, and then was very canny about using it. As she says in the film, “I started walking home, and it was such a pleasure, because all these people started to notice me, and I didn’t realize what a sweater could do.” There’s a certain disingenuousness about that, but I think it’s so great, because she suddenly caught the wind. That didn’t elude her. She saw it, she got it, and she knew exactly what to do with it. It’s that chemistry that I don’t think anybody can bottle. She wasn’t the most incredibly beautiful. When you look at some of those early shots, you wonder what possessed her to think she could become this person. She’s rather ordinary. Cute, but no Rita Hayworth. I think she was ready for the camera, and it was a real destiny for her.

Q: Tell us about the nude photos of Marilyn Monroe, some of which are included in the film.

A: They’re quite beautiful. The first nude sitting was the calendar sitting with Tom Kelley in 1949. She did it for money plain and simple. The only money she made off that sitting was $50 and the whole world has made nothing but money since. And one of them became the first Playboy centerfold in 1953. I think it was an innocent but also enjoyable session for her in the beginning. There’s nothing about it that’s sordid or lewd or tawdry or cheap. They’re very pin-uppy of that era; they’re gorgeous pictures. The Tom Kelley Studio was a very legit place. She loved it, and he is quoted as saying that she took to it like a dolphin to water.

At the time of The Misfits there’s a good story about her wanting to drop the sheets in the scene with Clark Gable in the bedroom and director John Huston said, no, I don’t need that. So she was very ready to do that. There are nude shots of her from Something’s Got to Give, which was the last film, which wasn’t completed, and she was nude in the film, in the swimming pool. There are also pictures of that. I don’t think to her it was ever a big deal. She kind of liked it, and she saw it as part of her own beauty.

Q: Do you think there are still any undiscovered photos?

A: Yes, there might be. I don’t know that this is true, but Phil Stern told us that after JFK died there was apparently sort of a tremor that went through the photographic community in L.A., that there may be some photographs of Marilyn that were taken somewhere around the Peter Lawford/Pat Lawford estate cavorting on the beach with JFK. Phil Stern said none of them ever materialized; he didn’t have them. But they may be out there.

Q: She was Playboy’s first and perhaps most famous centerfold. Do you think Hugh Hefner realized back then how keenly she’d come to be identified with the magazine and, indeed, the culture?

A: Maybe. He talks about it in the film, about the fact that when he got that photograph, she had become a starlet. So she wasn’t unknown. And when those photographs came to light she didn’t in any way deny it. She stepped right up to the plate; she laughed. It’s purported that she said “I had nothing on but the radio.” What Hefner talks about in the film is that this could have been quite scandalous as it had been for other people, and it didn’t hurt her at all. It didn’t even cause a ripple. So I think he was prescient in figuring that she was enough of a star, and could certainly be enough of a star to grace that first issue and, my God, look what he got since. She’s been an abiding presence for Playboy.

Q: What’s the most surprising thing about Marilyn Monroe that you learned from the photographers?

A: That she was really adored. She was late on movie sets, and she had a lot of trouble in the end. But there was something so intimate about her, and so sweet about her. And funny! She was unfettered by a bunch of junk. You know, she showed up herself. They all could get to her. And they all talk about how she lived in very unobtrusive places. Douglas Kirkland talks about her living in a very unimpressive little apartment in Hollywood. That last house, even in Brentwood, was a small house. There was nothing pretentious about her. There was nothing overblown about her.

I think, by and large, she was very surprised by all of it. Even though she knew that “Marilyn Monroe” was an entity that she had created and I think always thought of in the third person. Douglas Kirkland also tells the story of how that photograph with her holding the pillow was her favorite one. When she saw that photograph she said, “Now don’t you think that any man would love to be in bed with her?” So there was that disconnect – even with her – about who Marilyn Monroe was. And I think that surprised her on some level. She didn’t start believing her own press.

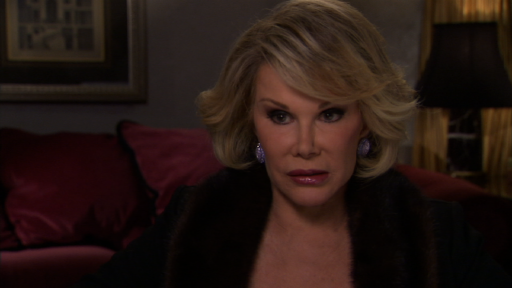

Q: In the film Gloria Steinem shared some very frank early assessments of Marilyn from her book. Do you think most women at that time felt the same way about her?

A: I don’t think she necessarily just saw herself as victimized and a sex object. She knew how to contend with it. I’m sure she was no fool about it. On the one hand, it was very flattering and great; on the other hand, it was probably awful and could be very lascivious and very terrible. But I think a lot of women just wanted to be like her. And that’s still true today.

Q: What about her relationships with men?

A: She was no fool about what men want, and who men are, and who they can be. She also loved men. But her heart got broken and I think she continually got taken the wrong way, and that finally had to take its toll. I think she was disappointed in her marriages. Joe DiMaggio, who was absolutely a man of his time – the great sports hero, the great baseball star, the great hitter of the 1950s – was never expected to understand women. He was expected to be the great icon. To understand a female icon alongside him was inconceivable.

A little aside to the night of the subway grate photo during filming of The Seven Year Itch was that DiMaggio walked off the street and went to Toots Shore’s restaurant. DiMaggio walked in upset, very upset, about the whole circumstance with Marilyn on the street, the dress going up, and Toots Shore, to comfort him and commiserate with him, makes an untoward remark about Marilyn. That was the end of the relationship with Toots Shore. So while DiMaggio was devastated by this, he would never have turned on her.

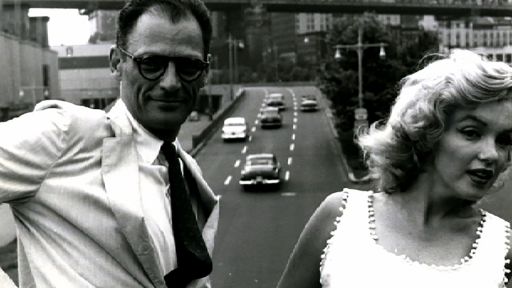

Arthur Miller, on the other hand, was equally unable to share the spotlight. And what’s also great about her is that she was never willing to give it up. I think Miller damaged her greatly. He seemed to belittle her, demean her. Norman Mailer, interestingly enough, would have just eaten it up. He’s never gotten over not having met her. In the film, he’s very outward about how he wanted to steal her. No question that she would have been a handful, but I think he would have done better than Miller.

Q: If she were alive today, do you think she would still be making movies?

A: One wonders what she would have done. She could sing. She wanted to be taken seriously. She also didn’t want to be forgotten as a babe. No question she would have stuck in the Strasberg ilk. She also had that great comic turn, which is no small talent. So those kinds of character roles could have continued for a long time. Who’s to know?

Q: Is there anyone alive today that has that same irresistible combination of charisma, star power, movie magic, and magnetism?

A: I don’t think there is. The insouciance of Marilyn is something modern women don’t have. The great line of Redbook editor Robert Stein was that she was in on the joke, and this is something Gloria Steinem missed, and I think was important. She was a joke to a lot of people, but she got it. She knew about it. And, boy, does she have the last laugh now. Actually, better than the last laugh – the last word. She kept it light, she had a soft touch, and I don’t think there’s a woman today who’s got that. She was a very rare creature, very delicate, very brilliant. She had this meteoric rise and then poof. And that was exactly what she was meant to do and be.