“Marvin Gaye”

by David Ritz

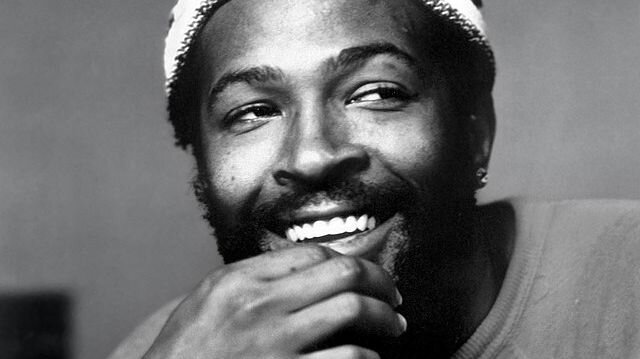

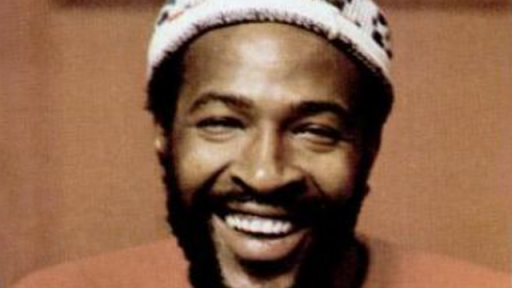

When Marvin Gaye died in 1984, he left behind one of the great legacies in American music. More than a superb vocalist and subtle composer, he was a visionary who expressed the tenor of his times. Both radical and romantic, a self-taught singer with a flair for autobiographical revelation, he thrived on confession and loved candor. Marvin had the unique talent of turning the listener into a confidante, of making you feel his immediate presence. His aura combined spiritual and sensual essences. In his music, the combination worked wonders; in his personal life, the two strains clashed. He succeeded in translating his contradictions into complex and beautiful music.

I adored Marvin Gaye. As we worked on his life story together, I saw him as a man of quick wit, rare wit and light-hearted humor. His boyish charm and infectious smile were irresistible. His paradoxes were fascinating. In the middle of conversations, he’d stop to meditate or pray, his words turning into songs. As a collaborator, he was fabulous — right there, in the moment, an ingenious improviser and natural storyteller.

Marvin Pentz Gay, Jr. was born April 2, 1939, in Washington, D.C. (He added the “e” after entering show business.) His father was a charismatic storefront preacher, his mother a domestic worker. Family life was marked by friction. Marvin grew up singing in his daddy’s Holy Roller church, the place he said, “where I learned the essential joy of music.” After working with Bo Diddley, Gaye left high school to join the Moonglows, an important doo-wop group of the fifties. It was Harvey Fuqua, the group’s leader, who took Gaye to Detroit in the early sixties. There Marvin met Berry Gordy, who just started Motown, and married Berry’s sister Anna, a woman 18 years Gaye’s senior.

Emerging from a generation rooted in conformity, Gaye was a non-conformist, an anti-authoritarian artist — shy, ambitious, mellow but fearful, brooding and serious. He began as a session drummer but soon was singing. He fashioned himself a Sinatra-styled balladeer determined to buck the Motown machine. Yet his early attempts at Nat Cole-flavored material failed. Gordy couldn’t crack the adult market and Marvin crossed over the same bridge as all the other Motown acts — red-hot rhythm and blues. Motown’s committee of crack producers helped create a slew of major hits for Gaye. The title of the first, “Stubborn Kind of Fellow,” was blatantly self-descriptive.

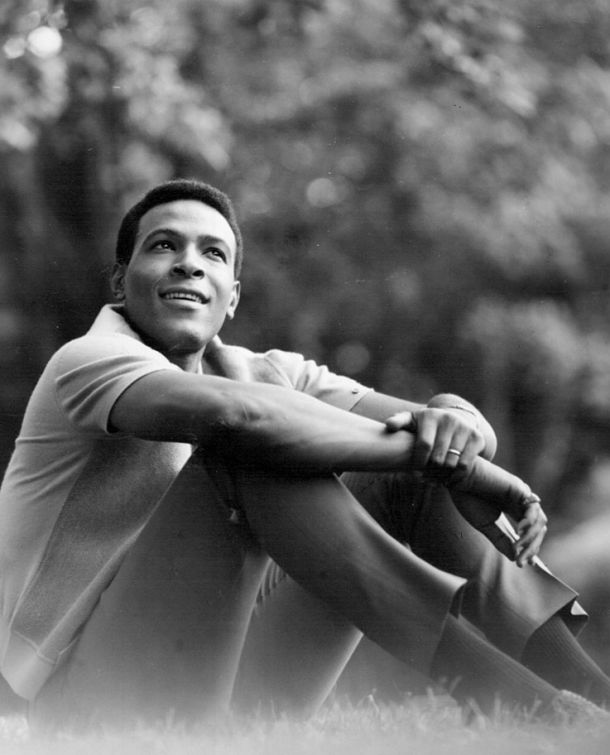

Marvin Gaye in 1966. Photo: J. Edward Bailey

Gaye’s sixties success centered on a series of brilliant singles supervised by various producers. Those songs established Marvin as a solo star. His work with Smokey Robinson (“Ain’t That Peculiar,” “I’ll Be Doggone”), Holland-Dozier-Holland (“How Sweet It Is,” “Can I Get A Witness”) and Mickey Stevenson (“Hitch Hike,” “Pride and Joy,” “Stubborn Kind of Fellow”) are among the crown jewels of early Motown. The productions explode with energy. Because of his flexibility and inherent musicality, Marvin was a producer’s dream. “You give Marvin material,” said Smokey, “and he’d improve, sculpt it, turn it into something bigger and better.”

His flexibility was also demonstrated as a duet partner. His most successful teaming was with Tammi Terrell, the standard against which all R&B duos are measured. As the country plunged into the Vietnam War, as race riots broke out across the land, the duets became escapes from reality. Marvin was a master of make-believe.

Meanwhile, his solo career found its greatest expression in the work of writer-producer Norman Whitfield. Both Gaye and Whitfield could be strong-willed and testy. But somehow the fiery blend of hostility and harmony came together in “I Heard It Through The Grapevine.” Marvin’s bone-chilling rendition carries all the pathos and pain of epic opera. “That’s the Way Love Is” and “Too Busy Thinking About My Baby” are also splendid examples of the wonders of Whitfield-Gaye.

“His Eye Is On the Sparrow” is a rare and moving instance of Marvin singing a spiritual non-pop song in the sixties.

The sixties was a producer-driven decade. In the seventies, Gaye changed all that. Now he thought in terms of concept albums, none more breathtaking than What’s Going On, the suite that reinvented soul music. After nine years of watching other producers, Marvin was ready to produce himself. The opinions of Motown’s marketing men, convinced What’s Going On would fail, didn’t matter. “What mattered,” said Marvin, “was the message. For the first time, I felt like I had something to say.”

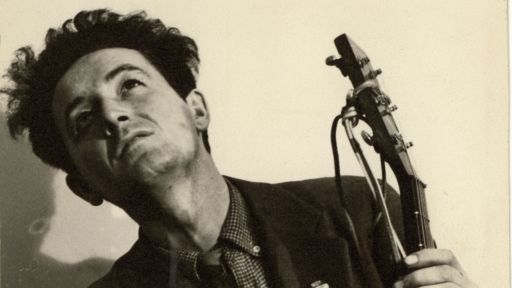

Released in 1971, the self-produced suite reflects a whirl of crosscurrents — silky rhythm-and-blues, string-laden pop, gospel sensibilities, free-form jazz. Tenorman Wild Bill Moore raged beneath the vocals with the fury of Pharaoh Sanders. Dave Van dePitte wrote and arranged the orchestrations; others helped Marvin write the songs; but in the end it is Gaye’s vision, Gaye’s passion, Gaye’s singular statement as an independent artist that creates this new aesthetic of American pop.

Marvin moved to Los Angeles in 1972 where he wrote his first score. Trouble Man was the film, its theme song an ironically autobiographical blues. (“I didn’t make it playing by the rules,” he sings. “Only three things that’s for sure — taxes, death, and trouble.”)

With few exceptions, the rest of the seventies was devoted to major suites. One exception is “You’re the Man,” a sparkling footnote to What’s Going On, written and produced by Marvin during President Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign. Another rare Gaye recording is “Where Are We Going?,” from his only session with producers Freddie Perren and Fonce Mizell. Heard [on The Very Best of Marvin Gaye (2001)] for the first time, Mavin’s version is the original to Donald Byrd’s, from the jazz trumpeter’s best-selling album Black Byrd. It has the sweet feeling of What’s Going On-light.

In 1973, Marvin finally answered What’s Going On with Let’s Get It On. Written in collaboration with Ed Townsend, the title song was an instant smash. The style is loose, funky and cavalier. Marvin basks in sensuous pleasures. He’s just met the young woman who would become his second wife, Janis Hunter, 18 years his junior. (Marvin and Anna wouldn’t divorce until 1977, by the time he and Janis had two children.) The suite is more than a celebration of sex. By the final chorus, Marvin seeks the spiritual, asking his lover is she understands what it means to be “sanctified.” “Distant Lover” stands as a towering ballad in the history of soul.

In the middle of the decade Marvin moved into his custom-built studio in the heart of Hollywood. In spite of the luxury of the new facility, though, Gaye suffered writer’s block. It took Leon Ware, a vastly underrated singer-songwriter, to break the block. The result was Ware’s scintillating production, I Want You. The title track is among Gaye’s most extravagant statements on physical longing, the album an euphoric and gorgeous piece of harmonic hedonism.

In 1977, Marvin needed a hit. The age of disco was in full flower. “Motown was screaming disco at me,” Gaye told me, “but I couldn’t be bothered.” Never one to chase fashions, Marvin was reluctant to concoct anything that remotely smacked of trendy dance music. Yet “Got To Give It Up” became a tremendous dance hit — #1 R&B, #1 Pop — and an eccentric success; it survives as a brief moment of levity during a period of Gaye’s personal despair.

Marvin and Anna finally divorced. Settlement negotiations were brutal. Here, My Dear, in 1979, documents that marriage and remains the most personal and intriguing of the great Gaye suites of the seventies. A meditation on emotional turmoil, “Anger” is a highlight from that monumental work.

“Ego Tripping Out” was the single selected from Love Man, a blatantly commercial album Marvin decided to shelve. The song can be seen as Gaye-styled rap, a testimony to the crippling properties of ego. It also denounces the drugs that are slowly killing him. “The toot and the smoke,” he sings on the concluding vamp, referring to cocaine and marijuana, “won’t fulfill the need.”

“Praise” is from Gaye’s final Motown album, In Our Lifetime, a series of wildly divergent musical essays, which, at their core, are unrelentingly dark. By then Marvin’s world was collapsing — his second marriage fell apart, his drug addiction flared out of control, the IRS seized his property. He moved from Los Angeles to Hawaii to London to Ostend, Belgium. With a contract from Columbia Records, he fashioned a dramatic comeback.

“Sexual Healing” remains an unanswered prayer. It is everything Marvin wanted, everything he needed, the reconciliation of his deeply divided soul. “Sexual Healing” meant serenity. When he recorded the song in Belgium in 1982, he was hopeful that such serenity was possible. It wasn’t meant to be.

In the end, despite a triumphant return to the U.S. on the heels of “Sexual Healing,” Marvin would not find happiness. His death at the hands of his father on April 1, 1984 tragically resolved a life-long struggle between the two men. Their relationship was marred by fear, jealousy, chemical abuse and fierce self-destructiveness. Their venomous antipathy was deeper than either man had understood.

A dozen years after his demise, Marvin’s contradictions remain. Discord and harmony echo through Marvin’s music like sweet incantations. When Gaye sings, the demons tyrannizing his soul are brought under control and made to conform to his elevated code of beauty. He achieves what Oscar Wilde called a “spiritualizing of the senses.” He endures; he remains an astounding artist, an inspiring poet, a man whose fabulous talents and all-too-human flaws worked together for the sake of song. The fact that Marvin lives on, now more than ever, is cause for celebration.

—

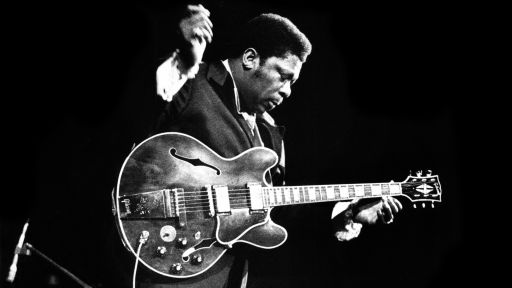

David Ritz co-wrote “Sexual Healing” and authored Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye as well as bios of Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, B.B. King, Smokey Robinson, Etta James and the Neville Brothers.