by David Vaughan

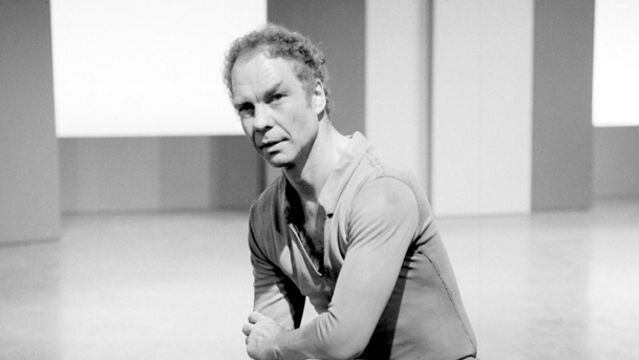

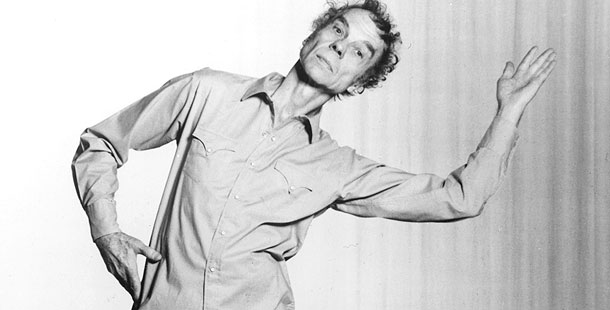

The title of Charles Atlas’ new documentary on Merce Cunningham may be taken quite literally: his mother described his dancing down the aisle of the church the family attended in Centralia, Washington, at the age of four. At 82, Cunningham is still making new work for the dance company he formed at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, in the summer of 1953. He has rarely stopped dancing, certainly not since as a teenager he took classes in tap and ballroom dancing from a local teacher. Even today, in spite of the physical limitations imposed by age, he still demonstrates to his company the movements he wants them to perform in class or in a new dance, and at the end of rehearsal every day he demands five minutes alone in the studio when he works by himself. As he has often said, his fascination with movement is as strong today as it was when he started.

Movement itself is the principal subject matter of his dances: neither narrative nor musical form determines their structure. His collaboration with the composer John Cage began with Cunningham’s first independent choreography, in 1942, and lasted until Cage’s death fifty years later. In the course of their work together they proposed a number of radical innovations. The most famous, and controversial, of these concerned the relationship of dance and music. In the early dances, dance and music shared an agreed time structure, coming together at certain key points but otherwise pursuing independent paths. As time went on, even those key points disappeared, and the relationship became still freer. The independence is now total–famously, the dancers in Cunningham’s company learn and rehearse a work in silence and often do not hear the music until the first performance, or at any rate the dress rehearsal.

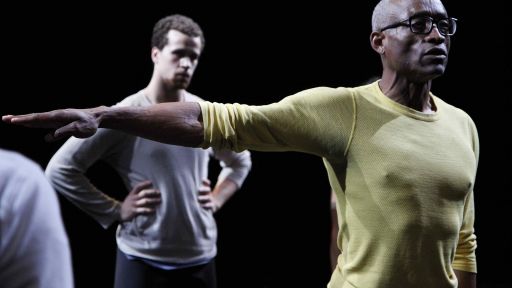

Other conventional elements of dance structure were also abandoned: conflict and resolution, cause and effect, climax and anti-climax. Cunningham is not interested in telling stories or exploring psychological states. This does not mean that drama is absent, but it arises from the intensity of the kinetic and theatrical experience, and the human situation on stage. Cunningham’s dancers are not pretending to be anything other than themselves-as he once said, “you are not necessarily at your best, but at your most human.”

The other principle that Cunningham and Cage shared was the use of chance procedures in the composition of their works. Cage carried them through to the process of realizing a work in performance, while Cunningham has preferred to use chance not in the performance of his choreography but in its composition. Even so, there are those who believe that the dancers toss coins in the wings before going on stage, where they improvise. Nothing could be further from the truth. By the time the choreography is given to the dancers in rehearsal, Cunningham has largely worked it out, using chance methods to determine the sequence of movements, where in the space they will be performed, and by how many dancers. His dances are not lacking in structure, but the structure is organic, not preconceived.

Paradoxically, Cunningham’s use of chance processes produces not chaos but order. Even in a chance piece, limitations are imposed by the existence of a gamut of available movement material from which the dance phrases must be put together-and, further, by the choice of that material that is then determined by chance. And chance results in unforeseen ways of placing the phrases in space and time. All the same, talent is clearly not excluded; as with any other way of composing, ultimately what counts is the quality of the imagination and craft that go into making the process work. If Cunningham is generally recognized as the greatest living choreographer, one reason for this is the sheer fecundity of his invention of steps: he likes to quote the story of a great tap dancer who asked a colleague, “have you made any new steps lately?” And that is what Cunningham does every day: any new work he makes starts, he says, with a step that will lead him to the discovery of something he did not know before.

David Vaughan is the archivist at the Cunningham Dance Foundation.