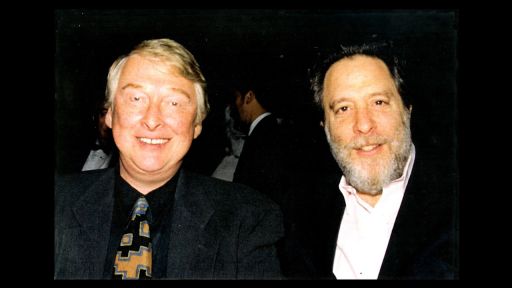

Director Mike Nichols, on set of film Charlie Wilson’s War, 2007.

©Universal/courtesy Everett Collection

By Peggy Noonan

This article originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal on Nov. 28, 2014, after director Mike Nichols died on November 19.

Mike Nichols was a learned man who loved his work and was in love with the world. I wrote of this two summers ago:

There was a 7-year-old boy who came over from Germany on the SS Bremen, traveling with his younger brother. They were fleeing the Nazis. The Bremen anchored on Manhattan’s west side on May 4, 1939, and the children were joined by their father, who was already in New York. They stood on deck watching all the bustle of disembarking when the boy saw something: “Across the street from where we were, and visible from the boat, was a delicatessen which had its name in neon with Hebrew letters,” he later remembered.

He was startled, then fearful. A sign in Hebrew letters—that would be impossible back home. He asked: “Is that allowed?”

“It is here,” said his father.

The little boy was Mike Nichols, the great film and stage director, who went on to do brilliant things with all that America allowed.

He died last week at 83, at the top of his game and still in the thick of it. I’m grateful this Thanksgiving just to have known him, and been his friend.

He was a great man.

We all know his work but it must be said he had such range. Everyone noted the past week that he did it all—directing on Broadway, in film, brilliant comedy act with Elaine May, comedy albums. And he had another kind of range. He had perfect pitch for the tale of a lost, affluent college graduate in the heart of Los Angeles in the 1960s, perfect pitch for a striving Staten Island working girl who wanted to make it in America in the ’80s, perfect pitch for the Midwestern working people whose story was told in “Silkwood.” He understood people! He saw their sameness, their hungers and hopes. He bothered to understand the country he first glimpsed from the Bremen.

He once told me he didn’t direct movies, he cast them. In a way it was a line and a typically modest one—it wasn’t him, it was them—but it also wasn’t. He was saying he picks actors who have the quality and depth to do what he wants, and he trusts them to come through. That is a great thing, when an artist trusts his paint.

There was something in the home that he shared with his wife, his beloved Diane Sawyer, that I always looked for when I visited. He kept a big, faded pillow on the living-room couch. It bore the words “Nothing Is Written.” When I first saw it I pointed. “You know what that’s from?” he asked. Yes, I said, “ Lawrence of Arabia,” Robert Bolt’s screenplay. He clapped his hands with delight. To know it was to honor what it meant—that no outcome is dictated, no impediment is insuperable; you can wrest life from its ruts, its false limits.

I can’t think of a better attitude for an artist, or any other professional for that matter.

His closest friends this week marveled at the depth of the impression he made on all whose lives he touched. “He’d make you feel you were better than you believed—smarter, funnier, more alive,” one said.

It was his way not only as an artist but as a human being to turn things on their head. A friend of his son, Max, wrote to remind him of a birthday party they’d attended years before, when she was a little girl. They had gone to see “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.” In the middle of it she ran out into the lobby, terrified. Naturally a parent would be expected to follow and comfort her by explaining it wasn’t real, there was nothing to be afraid of. But it was Mike who followed her out, and he asked, “Is being scared always such a bad thing?” A soothing philosophical discussion commenced.

A friend noted something else: his unbounded excitement about life, his ability to retain a freshness, an innocence. “It was always possible that this was going to be the best dumpling, the best conversation, this play was going to have a moment in it we’d never forget. . . . He was in love with the world. He was in love with Egg McMuffins! He took such joy in what was. Maybe the Buddhists have it wrong, maybe the great livers are the ones who love things, too—that book, that painting, the McDonald’s breakfast.”

A thing that distinguished Mike professionally is that he thought he had to know things. He came up in a generation that thought to know the theater you have to know the theater. They read. He read, all his life. He knew the canon—his Chekhov, Ibsen and Molière, his Shakespeare, Tennessee Williams and Tom Stoppard.

He learned his stuff in part for the sheer pleasure of learning, but in part because you have to know what has been said and thought and given to the world, you have to know what’s a cliché to be lost and what’s an ever-present truth to be resurrected or enlarged upon. Mrs. Robinson was, in fact, Phaedra. He knew, said a friend, that “every great story is a tremor from those dynamics that stretch back way over time.”

To make great art you have to know great art. And so his learned, highly cultivated mind. He dropped out of the University of Chicago and sought to teach himself through great books and smart people.

Great writers and directors have to start as great readers or it won’t work, nothing needed from the past will be brought into the future, and art will become thinner, less deep, less meaningful and so, amazingly, less fun, less moving and true.

The makers of American culture should return to this old style, which isn’t really old and yet is being lost.

Mike Nichols cared deeply—this was apparent in his later years—about keeping the American culture a thing of stature and height and radiance. It was the subject of our last long conversation, late this summer.

When he directed “Death of a Salesman” on Broadway two years ago he was, in fact, rescuing a classic and making it new again for those who had never seen or even known of this great play. He did a lot of rescue work. He wasn’t stuffy or old fashioned—that’s the last thing he was!—he loved the new, the breakthrough, the brave moment that he’d never seen before. But he wanted very much for us to retain and maintain the excellence of American theater and film.

An anecdote, about a friend who really got him:

The morning after Mike’s death, a friend of the family called those who had been in touch to invite them to a small gathering in New York the next afternoon. Among them was the actress Emma Thompson, who knew of his death and was bereft. Now, told of the gathering, she was crestfallen. She was in London, there was a big event months in the making the very next day, it wasn’t possible. Of course, she was told, we understand. Mike would understand.

The next day the gathering began, and first through the door was Emma Thompson. “Where else would anyone who knew him be?” she said.

Lucky us, that the Bremen came here.

———

Peggy Noonan is a columnist for The Wall Street Journal whose work appears weekly in the Journal’s Weekend Edition and on OpinionJournal.com. She is the author of nine books on American politics and culture. The most recent, “The Time of Our Lives,” was published in November 2015. Her first book, the bestseller “What I Saw at the Revolution: A Political Life in the Reagan Era,” was published in 1990. She was a special assistant to the president in the White House of Ronald Reagan. Before that she was a producer at CBS News in New York. In 1978 and 1979 she was an adjunct professor of journalism at New York University.