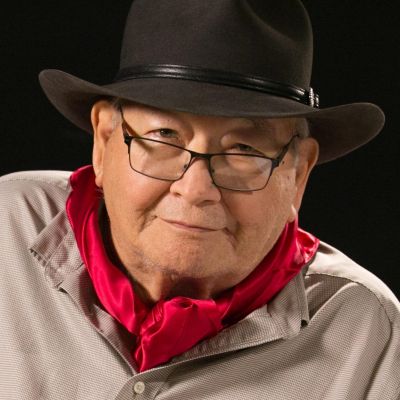

National Medal of Arts-winner Navarro Scott Momaday is a Kiowa novelist and poet. His Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “House Made of Dawn” led to the breakthrough of Native American literature into the mainstream.

In these highlights from an extensive interview conducted by director Jeff Palmer, Momaday reflects on the success of “House Made of Dawn,” the importance of oral tradition and wisdom for the future.

“I think man, mankind, has a tremendous capacity for adjustment and survival,” says Momaday.

In the 1960s, when you were writing “House Made of Dawn,” did you ever expect that it would win the Pulitzer?

No, no. I had no idea that it was under consideration at all. It came to me as a complete surprise. People don’t believe that but it’s true. I picked up the phone one day and my editor at Harper and Row, Fran McCullough said, “Scott, are you sitting down?” And I wasn’t but I should have been. She said, “You’ve been awarded the Pulitzer Prize.” I thought she was kidding and it took a while for it to dawn on me, and then people started coming to the door and it was a strange time in my life . . . As I say it came as a complete surprise, I was not thinking in those terms at all. But it became an important event, it changed my life in certain ways, as you might understand.

How did winning the Pulitzer Prize change your life?

Well immediately, I was a young professor at the University of California. We were all laboring under what was called, “Publish or Perish.” We were struggling to produce scholarship in order to maintain our careers. And so immediately the thing that changed with the Pulitzer Prize is I didn’t have to worry about publishing or perishing anymore. I had made my reputation, as it were, overnight. That was a big thing.

On the downside, or the other side of that coin, it was a little bit inhibiting. I had a hard time getting back to work after that. I suppose in my soul, or in my mind, I was saying, “How do you top that? What do you do next?” And so there was a kind of barrier to my work for a time. I overcame that luckily and of course it happens naturally.

It was an accident as far as I’m concerned. It was a great surprise to me, and I go on with my writing.

Did you go back to poetry or did you immediately go into writing another novel?

Yeah, you know, “House Made of Dawn” was kind of an aberration. I had been writing poetry exclusively. And in fact I went to Stanford to do my graduate work as a Creative Fellow in poetry. So I spent my whole time there writing poetry. And I worked myself into a corner, so I wanted more elbow room and I started writing a novel. And I did, I wrote the novel. But when I finished it, and when it was awarded the Pulitzer, I went back to poetry. . . I don’t consider myself a novelist. I spend most of my time writing poetry and painting. The Pulitzer Prize was a great thing in my life, of course.

In thinking about the oral tradition and landscape, and sovereignty [of Native people and Indigenous people], all of these things seem to be intertwined in some capacity in your work. How do those things work together?

I think that the landscape is a kind of sounding board for the oral tradition. The two things are inseparable really. We don’t know how old the oral tradition is. It’s probably as old as language itself. The landscape, which is the embodiment of spirit, in my view, is somehow informed with language and oral tradition. I think the voices of ancestors going back into geologic time are there. They’re in the landscape and when called upon they can be – they proceed out of the landscape and into the hearts of people. So I think there’s a definite correlation there.

Sovereignty, I think the Native American has lived on this continent for many thousands of years, since the last ice age certainly. So in that tenure, he has become one with the landscape, he has become a guardian of the natural world. It is his domain. So those things are all combined, it seems to me, in the oral tradition, the landscape, sovereignty.

When you think about your legacy, what is the one thing that you feel should be impressed upon? What would be the thing that you would want the youth to know or instill in them?

I would want them to be mindful of that fact that at the beginning of the 20th Century say, I was born in a house in Oklahoma, which had no electricity, no plumbing. We would be considered at the very bottom of the scale in terms of land and poverty. I came from that by the virtue of good luck and perseverance into a kind of existence that has been visible. I have achieved a kind of reputation and I think the legacy has to do with what is possible. It is possible to overcome great disadvantage. You know the Indian people, at the turn of the 20th Century, were terribly defeated. They had a sense of defeat. They had been conquered and put down and held down. And it was terribly hard for them to come out of that, to survive that kind of poverty of the morale, let’s say.

But they have done it to a large extent. There’s still a ways to go. I want my legacy to be the example of how one can survive against those odds. I think it gets easier all the time. The Native American is coming more fully into the general world than he was before and that is to the good. There’s still a lot to be done, as you say. . . to speak of Native Americans is one thing, but to speak of other cultures and populations in the world, we’re all facing a kind of crisis, it seems to me, at this point in time.

We’re threatened with warfare, general poverty that is decimating populations in the world. So, I don’t know. We’re at a crucial point. We talk about artificial intelligence and we have robots and all kinds of mechanical things going on that will change the world certainly, beyond our recognition. In another 50 or 100 years, we’re going to look back on this period of time, and that’s ancient history. It’s going to be a different world, and the question is how are we going to accommodate ourselves to it? How can we adjust to it?

I think we can. I have that much faith in humanity. I think man, mankind, has a tremendous capacity for adjustment and survival. It’s been true in the case of the Native American certainly. One could not see how he could survive 100 years ago. But, look, he’s there. And I think he will be there in the future. In what appearance, what guise, what costume, I don’t know. But I think he’ll be there. It’s the spirit that counts and the spirit is indomitable.

I want to give you the opportunity if you’d like to make a statement that you may have on your mind to put out to the world.

One of the things that I would like to say is that I think that storytelling is one of the great inventions of man. The acquisition of language itself, the oral tradition which goes back to the beginning of time, beginning of the acquisition of language. When somebody calls me a storyteller, I am just delighted. I can think of no greater name than that, the storyteller.