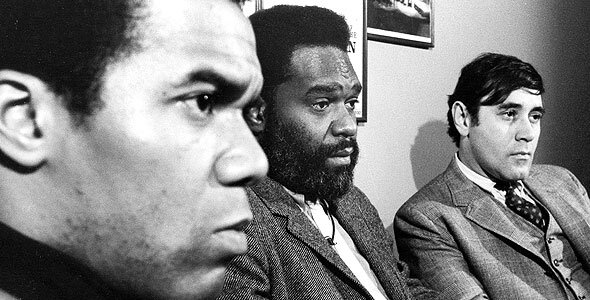

Prior to the 1960s, there were virtually no outlets for the wealth of black theatrical talent in America. Playwrights writing realistically about the black experience could not get their work produced, and even the most successful performers, such as Hattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen, were confined to playing roles as servants. It was disenfranchised artists such as these who set out to create a theater concentrating primarily on themes of black life. In 1965, Playwright Douglas Turner Ward, actor Robert Hooks, and theater manager Gerald Krone came together to make these dreams a reality with the Negro Ensemble Company. The main catalyst for this project was the 1959 production of “A Raisin in the Sun.”

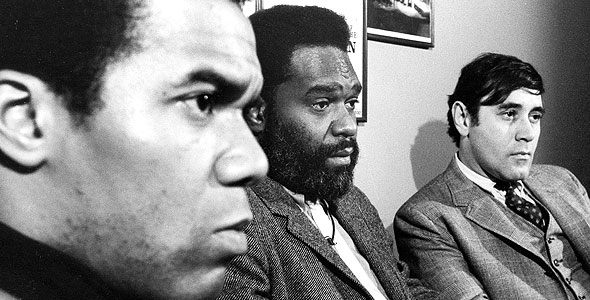

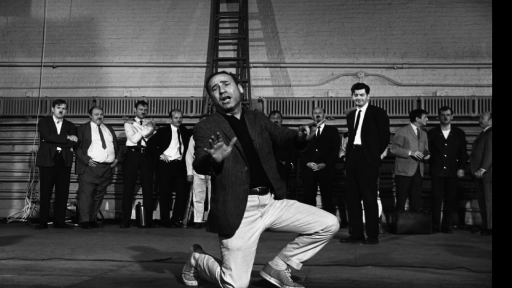

Written by Lorraine Hansberry, of “A Raisin in the Sun” was a gritty, realistic view of black family life. The long-running play gave many black theater people the opportunity to meet and work together. Robert Hooks and Douglas Turner Ward were castmates in the road company. Together they dreamed of starting a theater company run by and for black people. While acting in Leroi Jones’ play “The Dutchman,” Hooks began spending nights teaching to local black youth. In a public performance primarily for parents and neighbors, the kids put on a one-act play by Ward. A newspaper critic who had attended the performance recommended that Ward’s plays be produced commercially.

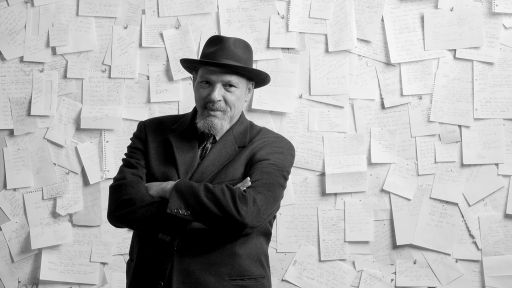

While Hooks raised money, Ward wrote plays. The pair recruited a theater manager, Gerald Krone, and the three men produced an evening of black-oriented, satiric one act plays. One of these short plays, “Day of Absence,” was a reverse minstrel show, with black actors in whiteface performing the roles of whites in a small Southern town on a day when all the blacks have mysteriously disappeared. The plays, performed at the St. Marks Play House in Greenwich Village, were a major success. They ran for 504 performances and won Ward an Obie Award for acting and a Drama Desk Award for writing. Impressed with his work, The New York Times invited Ward to write an article on the condition of black artists in American theater.

Ward’s piece in the Times became a manifesto for the establishment of a resident black theater company. With money from the Ford Foundation and a home at the St. Marks Playhouse, the Negro Ensemble Company formed officially in 1967. Though the new company succeeded in attracting audiences from all walks of life, they ran into a number of political and economic difficulties. In London a performance of the NEC’s first production, “Song of the Lucitanian Bogey” (1967) was heckled by-right wing protesters who resented its anti-colonial message. Back home in America, the group had to deal with criticism from members of the black community over their continued association with white administrators, playwrights, and funders.

Among the many plays produced by the Negro Ensemble Company were such greats as Peter Weiss’ “Song of the Lucitanian Bogey”, Lonnie Elder’s Ceremonies in Dark Old Men” (1969) and Charles Fuller’s “Zooman and the Sign” (1980). These plays dealt with complex and often ignored aspects of the black experience. Creating emotionally resonant characters with depth and variety, the NEC paved the way for black Americans to present a voice that had been aggressively stifled for three hundred years. This revolution in production and writing also meant an equally important advance for black actors. With the NEC, many black actors found their first opportunity to play characters with depth and meaning.

Though critically acclaimed and presenting some of the most important theatrical work of its time, the NEC ran into a number of economic troubles. With production costs rising and an original grant from the Ford Foundation gone, the group no longer had enough money for many of its projects. Even sellout audiences in the St. Marks Theater could not generate enough revenue to meet the budget. In the 1972-73 season the resident company was disbanded, staff was cut back, training programs canceled, and salaries deferred. The decision was made to produce only one new play a year.

Fortunately, the first play chosen was “The River Niger,” by Joe Walker. “The River Niger” was a moving play about the struggles of a black family from Harlem in the ’70s. It was the first NEC production to move to Broadway, where it stayed for nine months. It won the Tony Award for Best Play, and embarked on an extensive national tour. The success of “The River Niger” helped to insure the continued work of the NEC and of its many members over the next ten years. In 1981, the NEC had what was probably its most successful production with “A Soldier’s Play,” by Charles Fuller. “A Soldier’s Play” is a gripping story of the murder of a black soldier on a Southern Army base, and the subsequent investigation by a black army captain. It was a tremendously popular play and won both the Critics Circle Best Play Award and the Pulitzer Prize. It was later made into a movie, “A Soldier’s Story,” which was nominated for three Academy Awards.

Since its founding in 1967, the NEC has produced more than two hundred new plays and provided a theatrical home for more than four thousand cast and crew members. Among its ranks have been some of the best black actors in television and film, including Louis Gossett Jr., Sherman Hemsley, and Phylicia Rashad. The NEC is respected worldwide for its commitment to excellence, and has won dozens of honors and awards. While these accolades point to the larger success of the NEC, it has created something far greater. It has been a constant source and sustenance for black actors, directors, and writers as they have worked to break down walls of racial prejudice.