Picture a nation of patriotic citizens unencumbered by want or fear, free to speak their minds and worship as they chose.

Picture a nation of patriotic citizens unencumbered by want or fear, free to speak their minds and worship as they chose.

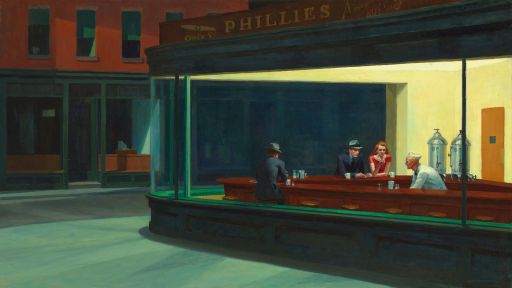

In a simple room, generations gather for a bountiful Thanksgiving feast. In a dimly lit bedroom, a mother and father tuck their child safely into bed. At a town meeting, a man stands tall and proud among his neighbors. In a crowd, every head is bent in fervent prayer. This is Norman Rockwell’s America as depicted in his famous “Four Freedoms” series. Although his vast body of work has often been dismissed or stereotyped, Rockwell remains one of 20th-century America’s most enduring and popular artists. Now, more than one hundred years after his birth, he is achieving a new level of recognition and respect around the world.

Norman Rockwell thought of himself first and foremost a commercial illustrator.

Hesitant to consider it art, he harbored deep insecurities about his work. What is unmistakable, however, is that Rockwell tapped into the nostalgia of a people for a time that was kinder and simpler. His ability to create visual stories that expressed the wants of a nation helped to clarify and, in a sense, create that nation’s vision. His prolific career spanned the days of horse-drawn carriages to the momentous leap that landed mankind on the moon. While history was in the making all around him, Rockwell chose to fill his canvases with the small details and nuances of ordinary people in everyday life. Taken together, his many paintings capture something much more elusive and transcendent — the essence of the American spirit. “I paint life as I would like it to be,” Rockwell once said. Mythical, idealistic, innocent, his paintings evoke a longing for a time and place that existed only in the rarefied realm of his rich imagination and in the hopes and aspirations of the nation. According to filmmaker Steven Spielberg, “Rockwell painted the American dream — better than anyone.”

Born in New York in 1894, Rockwell had early hopes of becoming an artist.

As a young man he left high school to attend art school. A diligent student at the Art Student’s League in New York, he graduated to find immediate work as an illustrator for BOY’S LIFE magazine. By 1916 Rockwell had created his first of many SATURDAY EVENING POST covers. He would continue to create memorable covers for them for nearly fifty years — making three hundred and seventeen in all. By the early 1920s, Rockwell had worked illustrating advertisements for many businesses, including Jell-O and Orange Crush. His work for magazines was growing in popularity and bringing in numerous requests. In 1920 he made a painting for the Boy Scouts of America calendar. Clearly one of the more well-known projects, he continued to work on their calendars until just before his death.

In 1942, Rockwell painted one of his most overtly political and important pieces.

In response to a speech given by President Franklin Roosevelt, Rockwell made a series of paintings that dealt with the Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. Throughout the mid-1940s these paintings traveled around the country being shown in conjunction with the sale of bonds. Viewed by more than a million people, their popularity was considered an important part of the war effort at home. During the late 1940s and 1950s Rockwell continued as one of the most prolific and recognized illustrators in the country. While his allegiance to the SATURDAY EVENING POST remained, he produced work for other magazines INCLUDING LADIES’ HOME JOURNAL, MCCALL’S, LITERARY DIGEST, and LOOK.

In the 1960s, prompted by his third wife, new markets, and by the times, Rockwell began to exhibit a strong sense of social consciousness. His images, which had primarily dealt with a utopian vision of the country, began to address realistic concerns. “The Problem We All Live With,” shows an African-American schoolgirl, escorted by safety officers, walking past a wall smeared with the juices of a thrown tomato. In addition to civil rights, Rockwell’s later subjects ranged from poverty to the Space Age, from the Peace Corps to the presidents.

Today, more than twenty years after his death in 1978, Norman Rockwell’s star is once again rising.

“Freedom From Want,” that inviting portrait of a New England Thanksgiving dinner, was recently the centerpiece of an exhibit at the National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. In an era of Abstract Expressionism, Rockwell never achieved the critical stature of contemporaries like Jackson Pollock, but his familiar images have found a permanent place in the American psyche.