Richard Linklater explores the rich contradictions of artifice and reality, theatre and film, love and desire in ‘Me and Orson Welles’

Written by Louis Black, this article was originally published by the Austin Chronicle on December 11, 2009. Read the original piece here.

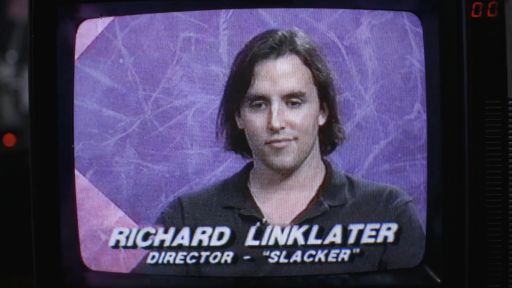

When entering a theater to see any film by director Richard Linklater for the first time, one can’t be sure what to expect. Clearly he tackles each film on its own terms, attempting some harmonic cinematic consistency between style, acting, story, and theme. This is so that each of his films will absolutely work as a sovereign entity with every aspect of the work complementing and supporting all the others. Over the last two decades, he has created one of the most exciting and brilliant bodies of work, but his hunger for new ideas may have led some to underestimate the quality and relatedness of his overall output.

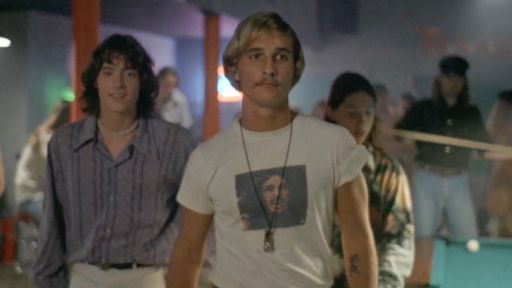

In past films he has pushed any number of narrative boundaries. Some films are exercises in reimagining cinema style (he’s shown a special interest in animation). Yet he has also made straight-ahead narratives that still ‘wow,’ even with their more traditional methods. Linklater has a clear affection for cinematic innovation, which is obvious in such films as It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, Slacker, Tape, Waking Life, and A Scanner Darkly. His range is such, however, that he is equally skilled and interested when making films with more traditional linear stories, styles, and textures: Witness Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise, School of Rock, The Newton Boys, Bad News Bears, and Before Sunset.

There are a few recurring motifs in Linklater’s films. Obviously he is interested in philosophy and metaphysics. There is something about conspiracy theories that attracts him. He loves sports and is interested in how culture makes meaning for different people in different ways. There is often a fascination with time; almost half his films occur in compacted periods of time (most often a 24-hour day). In Before Sunset he goes the distance in setting the film in real time – an 80-minute film about 80 minutes in the lives of two people. In Me and Orson Welles, Linklater’s latest film, the finite time is stretched to a full week.

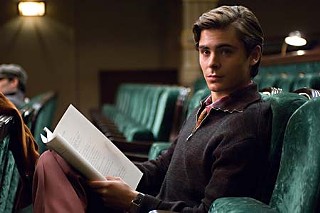

A period piece set in the 1930s about a famous but not-that-well-known history (the Mercury Theatre is constantly referenced in books but rarely explained), Me and Orson Welles is Linklater at his finest. The story, which was adapted by Holly Gent Palmo and Vincent Palmo Jr. from the novel by Robert Kaplow, is about a teenage actor named Richard Samuels (beautifully played by Zac Efron) who almost accidentally falls into a role in Julius Caesar, the Mercury Theatre’s debut production directed by and starring Orson Welles (Christian McKay). In Welles’ hands, the Shakespeare play has become a work of innovative, groundbreaking theatre, but there is only a week of rehearsals left before opening night. Carefully, the film explores a theatrical perfect storm of idiosyncratic personalities crashing together under the pressure of that impending deadline. The natural chaos of the week is intensified by the capricious, spontaneous, often-passionate, and just-as-often-arrogant genius of Orson Welles. There is no way Welles could not be at the center of the film, thus enriching the film’s focus on relationships, including those between actor and director, theatrical work and real life, adolescence and desire, affection and love, and of a genius with those around him.

Trying to consider the layering and texturing of as complex a work as Me and Orson Welles in a linear prose piece is going to fall short. There really is not that much of an age difference, for example, between the naive 17-year-old high school student Richard and Welles, the 22-year-old larger-than-life cultural legend. At no time in the film is this irony specifically noted, but over the course of the film, whether or not it becomes overtly apparent to the viewer, it still adds another layer of meaning.

Theatre itself is a world of illusion, and the film is about the many layers of illusion involved, not just the ones created for the audience, with so many intersecting planes dealt with in the most casual of ways. Without pretension, Me and Orson Welles deals with how the world of constructed fiction (a film, a play) articulates a story that is supposed to be of real life but, of course, is also constructed.

One of the few Linklater signatures evident in all his films is his skill at working with actors. It’s not just that there is rarely a bad performance in one of his films; it’s that all the skills the actors bring to the screen are in service of the characters and the story. Rarely does any single actor in his films give an overwhelmingly bells-and-whistles performance designed to stun you with its brilliance while casting a dark shadow over the rest of the cast. Instead, in every film the emphasis is on ensemble acting: The whole of the cast is better and more powerful than any one performance. Linklater believes in intensely rehearsing the cast before the film starts shooting, which bears results on the screen. Regularly Linklater gets some of his veteran actors to hit career highs, including Matthew McConaughey, Julie Delpy, Ethan Hawke, Keanu Reeves, and Jack Black (his performance in School of Rock is one of his best).

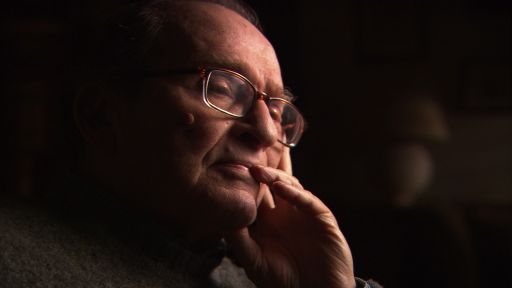

Linklater’s films typically focus on the kind of storytelling that works best with ensemble acting, and that is true of Me and Orson Welles and its consistently strong cast, too. Still, the most stunning aspect of the film is the incandescent portrayal of Welles by McKay, a former concert pianist who eventually turned to acting. (Me and Orson Welles is not McKay’s first take on Welles, which was in Rosebud: The Lives of Orson Welles, performed at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and in London, Toronto, and New York.) This is an astonishing performance, yet as much as it intrinsically draws attention to itself, its support of the overall film is not diminished. It is just that McKay’s Welles is so on-target Welles that there is no way he could not dominate the proceedings.

In the film Welles is a character played by an actor, but there is also the unavoidable cultural meta-presence of Welles because of his exaggerated grandiosity in his many film roles, TV commercials, talk show appearances, and his life, lived so large. The performance is so spit-perfect, however, that it is enriched rather than diminished by the layering of McKay as Welles with remembered fragments of the real Welles, from the newsreel footage at the beginning of Citizen Kane to his turn in The Third Man to him, impossibly fresh-faced, in The Lady From Shanghai.

Cliff Robertson starred as John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the 1963 film PT 109, about the future president’s heroics during World War II. There was one unforgettable review that said Robertson’s Kennedy strode the deck of the PT 109 as though he knew he would be president one day. It is impossible to read about Welles or watch his movies without witnessing his casual acceptance of his own genius.

Keep in mind that in 1937, the year in which Me and Orson Welles is set, the 22-year-old Welles had already made a name for himself in the theatre world. The next year he would soar into national legend when The Mercury Theatre on the Air presented its adaptation of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds on Oct. 30. Just a few short years after that, Citizen Kane would be released. This is the future of McKay’s character. Within the film, he walks the theatre’s stage with all the confidence, anger, energy, and impatience of Welles, but of Welles as a young man – sure, one who is arrogant, cocky, self-satisfied, and self-assured; one certain that the future will find him producing great work; but not one who is specifically aware of what is coming, knowing both just how high he will rise and then slowly fall.

Zac Efron certainly knows something about meteoric fame, having become a star as the lead in High School Musical, High School Musical 2, and High School Musical 3: Senior Year. Efron has had success on the stage, in television, and in films (Hairspray, 17 Again). His performance in this film as a young actor – somewhat cocky but also uncertain, very excited but also romantic – is on target, anchoring the film in ways that allow it and McKay’s bravura performance to work in concert.

Efron’s is one of those performances that requires the actor to do so much but in such a necessarily casual way that the yeoman’s work in the context of the overall film is easy not to notice. I’ve already read some reviews grading him as adequate but only adequate, which (as all too many current reviewers fall prey to) is more a comment on his fame than his performance. That this is a reaction to Efron’s greater public/media/cultural presence rather than a review of his performance is wonderfully ironic in that any movie with Welles as a character has to be more about the phenomenon of “Orson Welles” than about the man.

Often when a film’s subtext is this layering of artifice and reality, of created narrative theatre set against real-life theatrics (the roles we play for one another), by the work’s end, it’s become sophomoric. The complexity of all the layers having some validity, with life portrayed as a series of contradictions – sincerity with cynicism, romance with manipulation, desire with ego – is too often not even attempted. Instead the most complex difficulties of life are presented as mysteries with accessible solutions; the most complicated situations can be clarified and solved as easily as pulling back the curtain exposed the Wizard as just a man.

The ambitions of this film are more sophisticated. There is not one truth, but rather the complexities of the characters resonate against the many meanings of the narrative and the setting.

When dealing with love/sex/affection, too often works of fiction buy into the mythic. The romance is transcendent, and the lovers are more fantastic ideals than humans. The finite nature of film allows romance to be presented as an infinite rising of passion and interest. Rather than being forced to sustain the magic through the tortured course of everyday life, the film just ends. Thus it is never forced to deal with the mundane textures of everyday life to which even the most glorious mating of two mythic characters (instead of two people) must return.

There are a handful of films that take the myth to its celestial glory but then go back to Earth, where the characters go from being nobility to just being people. Among these are Last Tango in Paris, The Palm Beach Story, In a Lonely Place, and Linklater’s Before Sunset.

Me and Orson Welles offers romance and relationships (sexual, romantic, power, opportunistic), though that is just one of its threads. It is not as strictly focused on a relationship as the films mentioned above. Richard flirts (and more) with Sonja Jones, an attractive, career-oriented assistant at the Mercury (played by Claire Danes). Welles, a notorious Lothario, is also interested in her. What Sonja is most interested in is getting a meeting with David O. Selznick. In order for the film to not go flat, Danes has to negotiate a very tricky path on which she is genuine and honest, affectionate and ambitious. She has to be a fully developed three-dimensional character, a goal Danes nails as easily as a basketball superstar making a slam dunk.

The film works so well at evoking Welles and the people around him, the times, and history because the three fully realized lead performances are matched in skill by the entire cast.

While he wouldn’t conquer the cinema until the Forties, Welles’ remarkable theatrical career was already far along and well-established by 1937. At the age of 15, he both acted and directed at Dublin’s Gate Theatre. He debuted on Broadway at 18 in Romeo and Juliet. The next year he collaborated with John Houseman for the Phoenix Theatre Group and the Federal Theatre Project. At the latter, Houseman and Welles staged – or at least tried to stage – Marc Blitzstein’s very radical play The Cradle Will Rock. On what was to be the opening night, the theatre was actually closed down. Instead of giving up, Houseman, Welles, and company found another theatre where they put on the production.

In 1937, the 21-year-old Welles and Houseman founded the Mercury Theatre company. Julius Caesar was the debut production. The driving ideas behind the Mercury were the fostering of young talent and the unique and innovative staging of plays. Thus Julius Caesar was set in a fascist state, while the later all-black production of Macbeth was set in Haiti.

The Mercury Theatre company is the stuff of legend, and, sadly, a fast-fading one (the building that housed the Mercury Theatre, the Comedy Theatre on 41st Street and Broadway, was torn down in 1942). One of the great pleasures of Me and Orson Welles is that it gives an idea as to how these plays were staged. All histories relate that the plays were reimagined into cutting-edge, avant-garde works, but without ever getting a chance to see the plays, what does that really mean? Within the film, Linklater presents the play with an audacious theatrical ingenuity in which the staging is as crucial as the acting. Linklater’s efforts toward realizing the innovations of this play within a film enrich the work while mirroring his cinematic ambitions. In detail, in dialogue, in mise-en-scène, and in the characters and their interactions, the film is inventive and daring regardless of its narrative storytelling form.

As much as any working director and far more than most, each film by Linklater is a cinematic adventure, each its own fresh act of imagination and filmic storytelling. A restless cinematic talent, Linklater falls into no easy or repetitive categories. Linklater’s are never just films made to do well at the box office; they are works by a filmmaker who in some ways is working first and foremost for himself. This is not because of limited vision, outrageous egotism, or a lack of caring for the audience. By making the very best film he can make, he is not playing down to the audience or limiting himself to massaging only its lowest common emotional and intelligent denominators. Instead his determination is an act of absolute respect for the audience – one that on more than a few occasions has quite sadly not been reciprocated by them, especially at first.

In a creative writing class many decades back, the distinction was made between those who write for a living (or pleasure) and those who do so because they have to, because they are driven. The example of the latter was James Baldwin. The former lands on a desert island and can build a house, find a source of fresh water, figure out what there is around that can be eaten, and settle into a lifestyle. A writer will cut down the tree to make paper from the bark, will find berries or whatever to make ink and write. Without paper, ink, camera, or celluloid, Linklater would make movies. It’s what he does.

Funding for Richard Linklater – dream is destiny is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.