This piece was written by poet and activist Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio on January 13, 2020 in response to the proposed construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) atop Mauna Kea, a sacred dormant volcano in Hawai‘i.

“Maunakea has inspired a mighty wave of protectors to save a sacred mountain. Within the movement, new songs, chants, and stories are being birthed.”

Ask me about the mauna ⠀⠀⠀

And I will tell you ⠀⠀

How every morning I woke to a lāhui growing

As if we were watching Maui fish us

One by one

From the sea … ⠀

How on the third morning I watched ⠀⠀⠀

As 30 became 100⠀⠀⠀

then 100 became 1000 ⠀⠀⠀

then 1000 became us all⠀⠀⠀

Each and every one of our Akua standing beside us

— Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio excerpt from “Ask me about the Mauna”

On July 17, 2019, I watched alongside my Lāhui as 38 of our beloved kūpuna stood fiercely in their aloha for our ʻāina and were hauled away by State and Hawaiʻi County law enforcement officers. The Kūpuna had staged themselves in the center of the Maunakea Access road to block the transport of construction equipment up the mountain. Hundreds of thousands of people clung to their Facebook and Instagram live feeds while nearly a thousand kiaʻi, a sea of protectors, lined the Ala Hulu Kūpuna and flooded the pāhoehoe with our tears.

Just two days earlier, eight kiaʻi, myself included, had chained ourselves to the cattle guard on the access road to prevent the delivery of construction equipment. At 2 a.m I pulled on my cargo pants, my long-sleeve paddling jersey, and my hoodie with the words “See You on the Mauna” printed across it. In my pockets I carried only the essentials: lip balm, sunscreen, a vial of salt water from Kailua Bay, and a small bag of homemade cookies from my sister. Like most of my hoa aloha ʻāina I was severely underdressed for the cold. I worried that the midday heat would be too much to bear in my thermal gear, so underdressing was the choice many of us made.

Just two days earlier, eight kiaʻi, myself included, had chained ourselves to the cattle guard on the access road to prevent the delivery of construction equipment. At 2 a.m I pulled on my cargo pants, my long-sleeve paddling jersey, and my hoodie with the words “See You on the Mauna” printed across it. In my pockets I carried only the essentials: lip balm, sunscreen, a vial of salt water from Kailua Bay, and a small bag of homemade cookies from my sister. Like most of my hoa aloha ʻāina I was severely underdressed for the cold. I worried that the midday heat would be too much to bear in my thermal gear, so underdressing was the choice many of us made.

The eight of us ascended the access road together; we were joined by Kahala Johnson and Mahea Ahia who were our primary kōkua (supporters) and protectors. While we crawled upon the guard and locked ourselves into place we looked up in fear as a patrol vehicle sped recklessly down the mountain towards us. Malia Hulleman and I had just chained ourselves to each other and the grate when the bright lights began to approach us with alarm. Kahala and Mahea bravely put their bodies between us and the oncoming officer just as we put our bodies between the mauna and any construction vehicles. Without their protection any one of us could have been easily killed or severely injured. These were the first moments of what would be our 12-hour standoff with Hawaiʻi enforcement agencies.

The steel cattle guard pressed against our thin clothing and brought our temperatures down at a dangerous rate. I remember shivering so hard that my muscles began to ache. I looked in awe at the mana of Malia, the wahine who laid before me. When we walked up the access road that morning we were strangers, but by the power of aloha ʻāina we quickly became partners and eventually each other’s family. So I channeled all of the warmth I found in her eyes into steadying my pulse. I wanted there to be no mistaking my convulsing body for fear.

We were resolved.

We were honored to be chosen to take this stand for our ʻāina.

We were just simply freezing in the cold. Then, by midday, we traded the threat of hyperthermia for extreme heat exposure. Many of us resorted to cutting off pieces of our clothes to endure the climbing temperatures. The only thing we were unwilling to do was to stand down.

Frontline pilina in the malu of the mauna

by Jamaica Osorio

It’s Wednesday

And I find myself standing

In the shadow of a mauna that loves me like islands emerging from the sea

Like a sky scattering Herself in stars

Like a lāhui kanaka growing

I’m standing in the Malu of a movement

That’s captured an generations heart and attention

I find myself

Here

My body

A kīpuka expanding

Into pele’s pāhoehoe grip

Holding holding holding my quiet

It’s Wednesday and I find myself

Without searching

Arms linked with a line of women

I barely know

But was destined to love

A line of women stretching back for thousands of generations

Pō, turned light,

turned puko’a

turned slime

turned gods in a time of mere men

Who more fierce then these bodies of islands

They bodies of women

These moku turned ‘āina

Spilling into our sea of islands

These hands stretched out

Feeding a generation

Accustomed to starvation

And then Aunty tells me

We are the generation they always dreamed of

So it’s Wednesday and now I am weeping

And every kūpuna that ever fought,

ever cried, ever died

so that we would know for sure how to stand

Is singing through me

And somehow

Somehow i am still standing

Arms linked in a line of women

Holding me

And all I have to offer them

Is this story

That is incomplete

The Thirty-Eight

Names of the peaceful protestors, many of them kūpuna, arrested by state law enforcement officials on July 17, 2019 for blocking construction materials for the Thirty-Meter Telescope from being delivered via Mauna Kea Access Road:

James Albertini

Sharol Ku‘ualoha Awai

Tomas Belsky

Marie Alohalani Brown

Gene Burke

Daycia-Dee Chun

Richard L. Deleon

Alika Desha

William K. Freitas

Patricia Green

Desmond Haumea

Flora Hookano

Kelii Ioane

Maxine Kahåuelio

Ana Kaho‘opi‘i

Mahea Kalima

Kaliko Lehua Kanaele

Pualani Kanaka‘ole Kanahele

Deborah Lee

Donna Leong

Daniel Li

Carmen Lindsey

Linda Leilani Lindsey-Ka‘apuni

Abel Lui

Likookalani Martin

James Nani‘ole

Luana Neff

Deena Oana-Hurwitz

Edleen Peleiholani

Renee Price

Haloley Reese

Loretta Ritte

Walter Ritte

Raynette Robinson

Damian Trask

Mililani Trask

John Turalde

Noe Noe Wong-Wilson

As kiaʻi, we knew that it was both our responsibility and privilege to lay our bodies down in the protection of our ʻāina. With the guidance of our moʻolelo and kūpuna, we also knew that as kānaka we had the right to lie in the streets without fear of harm, invoking Ke Kānawai Māmalahoe, the Law of the Splintered Paddle. When we asserted ourselves upon that right, we challenged not only the Thirty Meter Telescope’s transport of construction vehicles, but the State of Hawaiʻi’s marriage to its colonial vision of law and order. We lodged this challenge not in chaos but rather within the organized adherence to our kānāwai, our Hawaiian governing norms, that have existed hundreds of years before the State took its first stolen breath.

After we had laid there in the malu, the shade and protection, of our mauna and our lāhui for over 12 hours, the police retreated in defeat. Aloha ʻĀina had won the day; we committed to each other and ourselves that we would be back for as many days as we are needed to until the TMT corporation leaves our islands.

After we had laid there in the malu, the shade and protection, of our mauna and our lāhui for over 12 hours, the police retreated in defeat. Aloha ʻĀina had won the day; we committed to each other and ourselves that we would be back for as many days as we are needed to until the TMT corporation leaves our islands.

On that day our commitment and aloha for each other and the mauna sent a call from Puʻuhonua o Puʻuhuluhulu to our lāhui across the world to join in the protection of our sacred Mauna a Wākea in the face of the proposed desecration from the development of a massive telescope on its peak.

The next morning, our numbers had increased from a couple hundred to nearly a thousand kiaʻi ready to stand and put their bodies between our mauna and any acts of desecration. We stood proud, basking in the wealth and brilliance of our people. We also stood anxious, because as our numbers grew, so did the numbers of officers, and their weaponry and machinery. As we grew to possibly the greatest activation of our people since the Kūʻē Petitions in 1897, a mass petition drive established by Hui Aloha ʻĀina (Hawaiian Patriotic League) against the annexation of Hawaiʻi to the United States, we wondered if we would be met with force that we, contemporary kānaka, had never before encountered.

In the wake of our rising wave, the State had assembled officers from at least six agencies. And while these officers collected their weapons—riot gear, sound cannons, mace, tear gas, and wooden batons—our kumu, masters of ceremony, lead us in the kāhea, the call, of our akua.

So when July 17 arrived, our lāhui was prepared. As police detained our kūpuna one by one, each empty seat was quickly filled by another kupuna, until all 38 elders there had been arrested. The rest of us, their moʻopuna, gave the officers only our silence. Not even the satisfaction of our wailing grief would surround them. And as our silence grew, so did our mana. I watched as our collective pain quickly and intentionally turned to action. And when the final kūpuna were hauled away, their places were flooded with hundreds of mana wāhine supported by our kāne at our backs. And again, our people controlled the road, controlled our destiny, and continued to protect our ʻāina.

When the mana wāhine took the road, we remembered the teachings of our kupuna. We sang our mele, chanted our oli, some even danced our hula. We offered aloha and care to each other and the police officers who stood in  opposition to us. We reminded them that we stood there for our children and their children. When the police brought out the LRAD / Sound cannon we passed around ear plugs and pule. We leaned into women we had just met sharing words of aloha and protection. We held tightly onto each other. We insisted that we would protect our lāhui as fiercely as we would protect our mauna. In that moment, we understood how the need to protect our people and our mauna were the same.

opposition to us. We reminded them that we stood there for our children and their children. When the police brought out the LRAD / Sound cannon we passed around ear plugs and pule. We leaned into women we had just met sharing words of aloha and protection. We held tightly onto each other. We insisted that we would protect our lāhui as fiercely as we would protect our mauna. In that moment, we understood how the need to protect our people and our mauna were the same.

The next morning, the number of kiaʻi who gathered at Puʻuhuluhulu and Ala Hulu Kūpuna had tripled. Day by day, we continued to grow. Three to five thousand kānaka and allies answered the call to kiaʻi our mauna. The wealth of our mana resounded across the pae ʻāina while the State spent more than $10 million on its threat to remove us from our ancestral lands.

For the Lāhui

By Josh Tatofi

Lyrics by Hinaleimoana Wong

E welo mau loa ku‘u hae aloha

I ka nu‘u o ka lewa lani lā

A e maluhia no nā kau a kau

Eō Hawai‘i ku‘u ‘āina aloha

E ku‘u lāhui e

Wiwo ‘ole e

Kū kānaka e

‘Onipa‘a mau

Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono

Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono

Translation:

My beloved flag waves ever more

in the last year‘s heights of the sky.

Always and forever more in peace and tranquility

Hail your name, oh Hawai‘i, my beloved motherland

To you my nation

Be bold and fearless,

Stand as kānaka,

And be steadfast in your place.

For the freedom of our land remains always in the truth of our people.

And today our movements continue to grow. Our kiaʻi continue to govern the Ala Hulu Kūpuna with aloha ʻāina, in strict kapu aloha. Our people are rising like a mighty wave, and what we have accomplished cannot be cast aside. In less than three months, our movement brought thousands of people to the mauna physically (and hundreds of thousands virtually). Most of these kiaʻi had never stood in the Mauna a Wākea’s malu prior. That’s thousands of people who had never had the opportunity to develop an intimate pilina, a closeness, to one of our most sacred ʻāina.

Through our collective ea, our independence, our breath, and our commitment to aloha ʻāina, we brought these kānaka home. And in doing so, we have cultivated in our people an intimacy with a part of our ʻāina we had been strategically estranged from. We should celebrate the many ways our people are returning to an aloha ʻāina that are not simply political but are also deeply intimate and emotional. The growing intimacies between each other and our ʻāina is our greatest wealth because it is what makes us Kanaka Maoli in the first place.

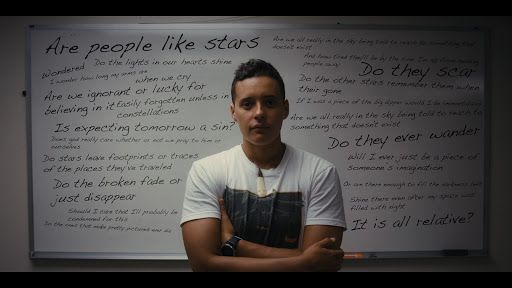

And as we continue to assert ourselves as kanaka we do so through the greatest creative outpouring of our collective lifetime. Song writers, poets, kumu hula, filmmakers, and playwrights are all taking part in telling and protecting this moʻolelo. We are writing the histories of our time in our own voices, with our own melodies and dancing them with our own bodies, just as our kūpuna did for us when they composed mele like “Waika,” “Kaulana Nā Pua,” “Ka Mamakakaua,” and “All Hawaiʻi Stand Together.” Our creativity both describes and expands our current movement. Because of our commitment to the moʻolelo of our rise, our moʻopuna will sing, dance, and speak of the brilliance of our movement to protect Mauna a Wākea long after we have passed into the realm of pō.

Kānaka living around the world are also taking these lessons of aloha and pilina to their home communities. And so, as we continue to grow together in aloha for each other and our home, we must remember that it was this very intimacy of aloha ʻāina that pulled islands out of the depths of the sea, that called upon the great koa (warriors) of our history to fight against a variety of oppressive forces, and that mobilized kānaka opposition to U.S. imperialism and annexation. The intimacy of aloha ʻāina carried 15,000 Native Hawaiians to march to the ʻIolani Palace in 1993 in recognition of 100 years of being a stolen kingdom. In 2018, aloha ʻāina called another 20,000 to return to that march to celebrate the vibrancy of our resilience and resurgence. Putting this intimate aloha ʻāina to action today has resulted in similar uprisings in our communities in Waimānalo, Kalaeloa, and Kahuku and will surely empower the continued rising of our kiaʻi on Maui and Kauaʻi.

I believe it is only a matter of time until the Thirty Meter Telescope corporation packs up its bags and departs our beautiful home. But we must always remind ourselves and our opponents that we are not simply standing in opposition to desecration; rather, we are fearlessly committed to protecting our humanity and our ability to live, breathe, think, and act as our kūpuna have for generations. This movement reminds us that protecting ʻāina is what makes us Kānaka in the first place. From where I stand, that is the wealth of our ʻike kūpuna that we surely cannot afford to lose.