TRANSCRIPT

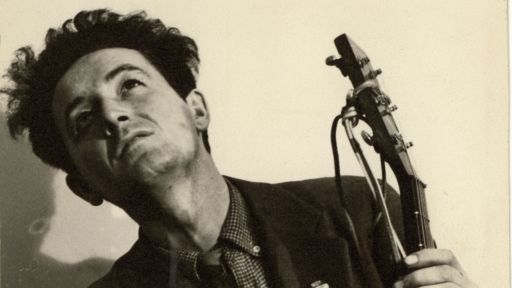

- I think improvisation, I think our generation, our particular generation, was very, we were set up for that through jazz, I really believe.

I think that in 1963 when I was a teenager, the biggest thing was Coltrane.

'My Favorite Things' came out, and, of course, there Miles Davis, and there was various things happening, Roland Kirk.

But I think Coltrane, I often think that Jackson Pollock and Coltrane informed a lot of what my, a certain, a certain facet of my generation.

You have people like the Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix.

There's, I think that, it was, we were helped, we were primed for that through listening, listening to Coltrane.

And I think, maybe not even intentionally, but I think it freed a lot of us, or if not freed us, gave us a new structure, because the rock-and-roll song structure is great.

It's great to dance to.

It's great release, but we were really ready for a new structure.

We were really ready to open that structure.

I always give thanks to Coltrane.

Often right in the middle of an improvisation, he passes through my mind.

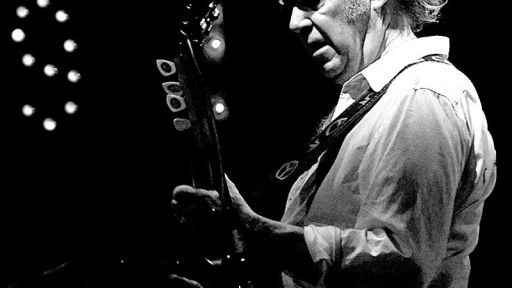

- [Interviewer] You're credited with bringing the music scene away from glam rock and back to plain clothes to the three basic chords to... Could you paint a picture for me about the music scene of the 70s?

CBGBs, the punk new waves, all that.

Set the stage for what was going on?

- The early 70s, for me, in terms of rock-and-roll, was a very difficult time.

We lost some very strong forces, losing Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin.

And then people like Bob Dylan, or even the Rolling Stones, people that we were counting on, sort of retreating or regrouping, and the things that were becoming very prominent, at least for me, seemed very theatrical, very limited, in terms, lacking spiritual content and having a lot to do with image, but not in the way that, you know... Image was very important in terms of, like, Blonde on Blonde and the Velvet Underground and the way Jimi Hendrix dressed.

But it didn't, it wasn't at the sacrifice of spiritual content.

And I really felt that that political and spiritual content was losing out, and we were being confronted with basically image, and I felt that was something worth fighting.

And we were also experiencing probably, like, some of the death throes of folk music.

And there had to be some kind of something.

Something had to shake things up within the underground area.

Something had to erupt.

I didn't have, myself, a lot of personal ambition.

My ambition at the time was to sort of, I always felt like the boy who puts his finger in the dike, until the troops come or the people come to save the day.

I really didn't feel that I had, I was qualified to save the day myself, but I really felt that I could hold things, do something, be of some avail, until some new forces came about.

And I think that with my band, we accomplished that.

Because the idea wasn't to open this area up for ourselves.

The idea was to open it up and remind people that this is a genre, a very physical, American genre with endless possibilities, and it belonged to whoever had the energy and the vision to take a hold of it and make that coal into diamonds.

It didn't belong to marketing crews and well.

Anyway, that was sort of what it was like.

I guess.

I sat and thought about my personal chronology with the Velvet Underground, and I remembered that my introduction to the Velvet Underground was entirely visual.

Living in a rural area of South Jersey, I was very much involved with the work of Bob Dylan and read a lot of poetry, of course, myself.

But what I knew of the Velvet Underground was really through photographs.

There was a huge exhibition in Philadelphia, an Andy Warhol exhibition, in the mid-60s, and that was very exciting and very foreign to me, being a girl in South Jersey.

And I found through Andy Warhol, specifically a book, I believe by Billy Name, of black and white photographs, and so my whole relationship with the Velvet Underground was entirely visual.

I'd never heard their music.

All I knew was the silver Mylar pillows, the dark glasses, the grainy skies, the water cisterns?

What do they call them? Water towers.

It's like my whole relationship with the Velvet Underground was image.

And of course it was a very strong image, from the boat-neck shirt to again, the Ray-Ban-style glasses.

And when I eventually came to New York, by the time I came into the Chelsea Hotel, which was 1969, they had already disbanded.

And so all of my knowledge of the Velvet Underground was through other people expounding about them.

People like Donald Lyons or Lenny Kaye or Lisa Robinson, people in the Chelsea Hotel.

They all spoke of the strength and the power and how much the Velvet Underground so completely encapsulated the city.

And I really didn't see them until they converged again at Max's Kansas City in the very early 70s.

Donald Lyons took me to see them.

He really wanted me to hear the Velvet Underground 'cause I hadn't yet heard them.

I hadn't had any of their records.

And so it was very interesting to sonically hear what I had only known by sight.

And I was, the two things I was taken with, and that I related to personally, was, one, their cerebral surf rhythms, which I could very much relate to, and the way that Lou phrased his language over it, which I mean, I thought it was very cerebrally sensual music, and it was satisfying for me.

It was intellectually satisfying without being pretentious or standoffish.

And I, well, I liked them very much.

But I think that what kept me, what kept me very interested in them was Lou, obviously, very well-read, his poetics though, were quite crystalline and simple.

He had a way of taking mounds of knowledge and paring it down to a few lines.

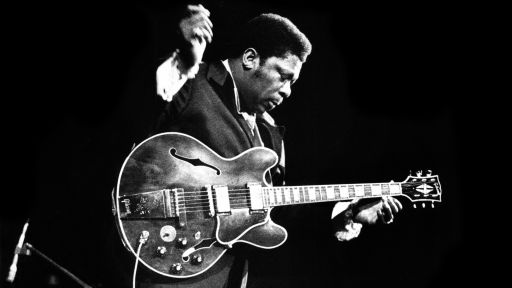

But 'Heroin' is a song and is a work of art, to me is one of our more perfect American songs, because it addresses a very conflicting subject, a subject that has so many stigmas attached to it.

It addresses all of the deeply painful and destructive elements of it and also whatever is precious about it in one piece, in a nonjudgmental piece, in a non-preaching piece.

And just with, again, Lou's such beautiful, simple, direct language.

I mean, I find, I mean, after all of the first two verses that are very descriptive and very strong and very, they seem so beautifully masculine with this very feminine rhythm, feminine being that it just, if you imagine the sensual part of it, that it quietly cascades.

It's not like a fast spurt. It quietly cascades.

So I think it's a very beautiful mergence of the masculine and feminine.

And then, he just leaves the whole thing with this little, 'I wish that I was born a thousand years ago.

I wish that I had sailed the darkened seas on a great big clipper ship.'

I mean, it's just like any boy's dream.

I mean, it's like, any part of him that was going through a conflict, pain, about what he was doing, about the drug itself, about his life, for a moment, a beautiful clarity, he expressed the boy's dream, and I just think that's so beautiful, really.

I found that that song, because, especially at the end of it, where it took me just in listening was to a black expanse with a spray of stars and this Wynken, Blynken, and Nod ship, this boyhood ship going through the night skies.

- [Interviewer] What is it about rock-and-roll where if you write in the first-person, they think it's autobiographical.

Whereas if you're Shakespeare, you can write it, and it doesn't... - I don't know, because I have had that difficulty throughout my own, my own time as a worker.

I mean, I find it amazing that if you, if I, that people are immediately ready to categorize you if you shift gender in a song, or you know, I've often in my work been the predator, the rapist, the murderer, or the one admiring a beautiful female, and people immediately want to categorize each thing.

And I think it's media.

I think it's really media, and just our tabloid consciousness.

I was amazed when I was confronted with that.

I used to say to people, well, when Hemingway created these really great women and spoke as them, like Brett or something, did that make him a cross-dresser or something?

We're in a very label-conscious time, which I find really unfortunate.

Artists never like to be labeled.

I remember reading, even though I always found the term, something like 'action painter,' a very cool term, Jackson Pollock didn't wanna be called an action painter.

He was an artist.

I myself, I don't really like being called a female vocalist, which I find absurd.

They don't call, it's like calling Jim Morrison a male vocalist, or Picasso, a white painter.

And they always, people seem very, very label-conscious, but we can take this into anything.

I really, it's one of my things that I find disturbing and sometimes humorous, but I really look forward to a time where we don't have to, where I don't have to pick up a book and read that this person is a gay poet, a black artist, a female artist.

I think if people's work is heightened to where it should be, if a person has a calling and really, truly articulates that calling, there needs to be no label, no matter what that particular calling is.

And I look forward to a time when people are, relate to each other in terms of their, how they exemplify themselves, how they carry themselves as a human being.