Paul Robeson was the epitome of the 20th-century Renaissance man. He was an exceptional athlete, actor, singer, cultural scholar, author, and political activist. His talents made him a revered man of his time, yet his radical political beliefs all but erased him from popular history. Today, more than one hundred years after his birth, Robeson is just beginning to receive the credit he is due.

Born in 1898, Paul Robeson grew up in Princeton, New Jersey. His father had escaped slavery and become a Presbyterian minister, while his mother was from a distinguished Philadelphia family. At seventeen, he was given a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he received an unprecedented twelve major letters in four years and was his class valedictorian. After graduating he went on to Columbia University Law School, and, in the early 1920s, took a job with a New York law firm. Racial strife at the firm ended Robeson’s career as a lawyer early, but he was soon to find an appreciative home for his talents.

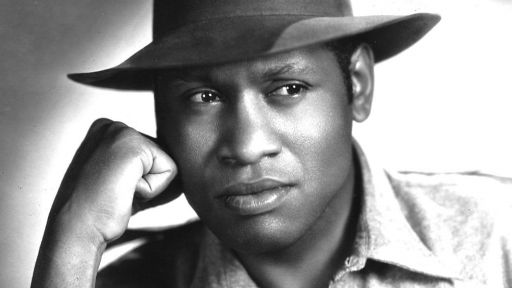

Returning to his love of public speaking, Robeson began to find work as an actor. In the mid-1920s he played the lead in Eugene O’Neill’s “All God’s Chillun Got Wings” (1924) and “The Emperor Jones” (1925). Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, he was a widely acclaimed actor and singer. With songs such as his trademark “Ol’ Man River,” he became one of the most popular concert singers of his time. His “Othello” was the longest-running Shakespeare play in Broadway history, running for nearly three hundred performances. It is still considered one of the great-American Shakespeare productions. While his fame grew in the United States, he became equally well-loved internationally. He spoke fifteen languages, and performed benefits throughout the world for causes of social justice. More than any other performer of his time, he believed that the famous have a responsibility to fight for justice and peace.

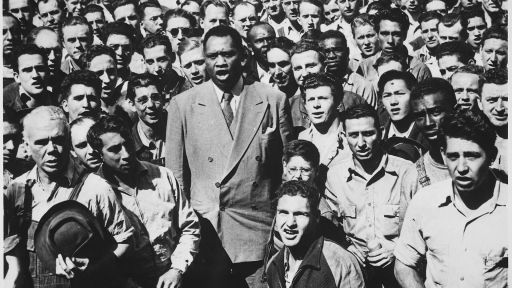

As an actor, Robeson was one of the first black men to play serious roles in the primarily white American theater. He performed in a number of films as well, including a re-make of “The Emperor Jones” (1933) and “Song of Freedom” (1936). In a time of deeply entrenched racism, he continually struggled for further understanding of cultural difference. At the height of his popularity, Robeson was a national symbol and a cultural leader in the war against fascism abroad and racism at home. He was admired and befriended by both the general public and prominent personalities, including Eleanor Roosevelt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Joe Louis, Pablo Neruda, Lena Horne, and Harry Truman. While his varied talents and his outspoken defense of civil liberties brought him many admirers, it also made him enemies among conservatives trying to maintain the status quo.

During the 1940s, Robeson’s black nationalist and anti-colonialist activities brought him to the attention of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Despite his contributions as an entertainer to the Allied forces during World War II, Robeson was singled out as a major threat to American democracy. Every attempt was made to silence and discredit him, and in 1950 the persecution reached a climax when his passport was revoked. He could no longer travel abroad to perform, and his career was stifled. Of this time, Lloyd Brown, a writer and long-time colleague of Robeson, states: “Paul Robeson was the most persecuted, the most ostracized, the most condemned black man in America, then or ever.”

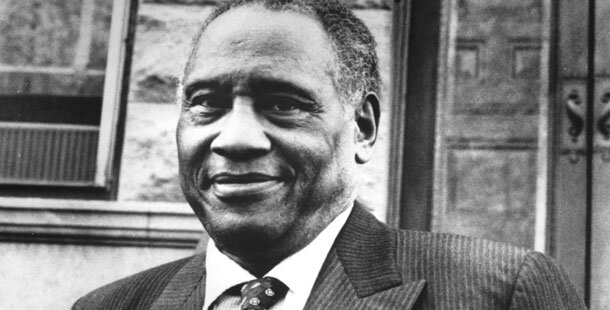

It was eight years before his passport was reinstated. A weary and triumphant Robeson began again to travel and give concerts in England and Australia. But the years of hardship had taken their toll. After several bouts of depression, he was admitted to a hospital in London, where he was administered continued shock treatments. When Robeson returned to the United States in 1963, he was misdiagnosed several times and treated for a variety of physical and psychological problems. Realizing that he was no longer the powerful singer or agile orator of his prime, he decided to step out of the public eye. He retired to Philadelphia and lived in self-imposed seclusion until his death in 1976.

To this day, Paul Robeson’s many accomplishments remain obscured by the propaganda of those who tirelessly dogged him throughout his life. His role in the history of civil rights and as a spokesperson for the oppressed of other nations remains relatively unknown. In 1995, more than seventy-five years after graduating from Rutgers, his athletic achievements were finally recognized with his posthumous entry into the College Football Hall of Fame. Though a handful of movies and recordings are still available, they are a sad testament to one of the greatest Americans of the twentieth century. If we are to remember Paul Robeson for anything, it should be for the courage and the dignity with which he struggled for his own personal voice and for the rights of all people.