“I get my energy, I think, from being afraid to choreograph, being afraid to fail.”

In 1952, a 22-year old athlete with little training or experience won a work scholarship to the American Dance Festival.

Powerfully built, he immediately captured the attention of dance giants Martha Graham, José Limón, and Doris Humphrey. This young dancer had a commanding presence, instinctive talent, and a unique way of moving. Taylor was invited to join the Martha Graham Dance Company, where he began his professional career. While starring as a soloist with Martha Graham’s company, Paul Taylor assembled The Paul Taylor Dance Company. Throughout the long career that has followed, his company became one of America’s premier troupes. Today, Taylor is considered by many to be the greatest living choreographer.

Born in Wilkinsburg, PA, in 1930, Taylor had a turbulent and lonely childhood, often separated from his parents. After attending Syracuse University on scholarships in painting and swimming, he began to study dance. Two years later he joined the Martha Graham Dance Company, where he performed in a number of pieces, including “Clytemnestra” (1958), “Alcestis” (1960) and “Phaedra” (1962). While still with the Martha Graham Dance Company, he danced for a number of other great contemporary choreographers, including Merce Cunningham and George Balanchine. It was, however, with his own dance company, which he founded in 1954, that Taylor made his greatest contribution to the art of dance.

In the mid-fifties, as New York was confidently asserting its position as the major cultural center for the arts, Taylor’s emerging talent was beginning to be recognized. Excited by the experimental arts of the time, Taylor became friends and collaborators with the painters Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Taylor shared their desire to bring the vernacular into high art. Using gestures and stances from the street, Taylor’s work reflects the beauty and pathos of society. In a number of his early pieces, Taylor composed dances of everyday gestures, such as checking a watch or waiting for a bus. Once seen separated from their context, one can recognize the richness of these everyday movements. For Taylor, a dance is the first step in returning the viewer to the street more aware of the beauty in the simple movements he or she sees every day.

Throughout the late 50s, 60s, and 70s he performed some of the most exciting and inventive dances of the time. “Duet” (1957) was an experimental piece in which Taylor stands next to a reclining woman in street clothes, and neither one moves. This four-minute piece was a distillation of many essential elements of dance, calling attention to posture and the interconnection of people within a space. Similar to other minimalist experimental artists of the time, Taylor’s break with convention was simply a starting-off point for further investigation. His later pieces combine this minimalist performance with ballet. Among the best known of these are “Three Epitaphs” (1956), “Orbs” (1966), “The Book of Beasts” (1971), and “Airs” (1978). His “Aureole” (1962) is one of the most highly respected dance works of the time for its grace and technical difficulty. It is Taylor’s combination of the subtlety of ballet with the spontaneity of everyday gesture that has made him such a powerful force in modern dance.

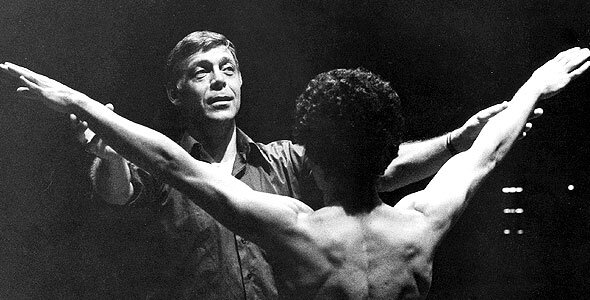

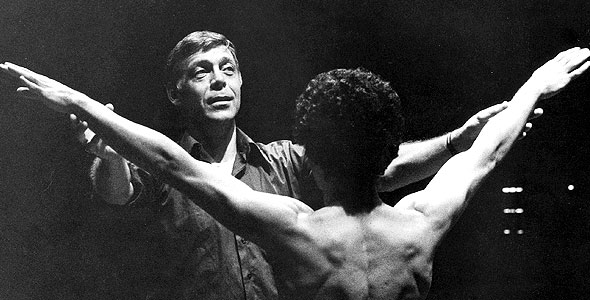

No longer dancing himself, Taylor has spent the past two decades devoted completely to directing his company and teaching the younger generations the rigors and beauty of dance. Taylor continues to find his inspiration both in the streets and in the studio. For him, watching the dancers move and responding to those movements is an essential part of his work. In this way the choreography becomes both an individual and communal endeavor. Among the dancers to move through his company on the way to starting their own were Laura Dean, Twyla Tharp, Dan Wagoner, and Senta Driver. Through these students and through the continued productions of his dance company, Paul Taylor’s work continues to inspire people throughout the world.