In this film excerpt, see Pedro E. Guerrero’s photographs of Alexander Calder’s mobile and stabile sculptures in open landscapes, at Lincoln Center in New York City, and in Spoleto, Italy. Guerrero captured the art works’ relationship to space, to the workers who created them, and to the public that observed them. Guerrero and Professor Joan Marter, who knew both Calder and Guerrero, provide commentary on the sculptures and the photos.

Pedro E. Guerrero: A Photographer’s Journey – Book Excerpt

By Pedro E. Guerrero. Published in 2007 by Princeton Architectural Press. Used by permission of Pedro E. Guerrero Archives. In the chapter Calder’s Universe, two portions excerpted here, Guerrero describes his work with fellow American Master Alexander Calder.

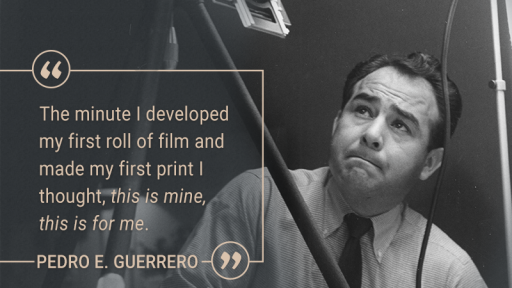

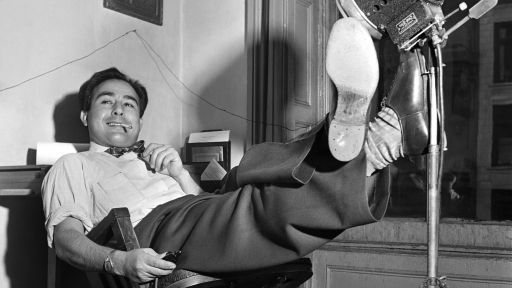

AFTER FIFTEEN YEARS OF SHOOTING STATELY MANSIONS with manicured lawns, gorgeously outfitted living rooms, and spotless kitchens, photography was becoming routine. So I was intrigued in 1963 when Elizabeth Burris-Meyer, House and Garden’s kitchen editor, asked me to photograph Alexander Calder’s home in Roxbury, Connecticut, for a story entitled “A Man’s Influence in the Kitchen.” I knew Calder (1898–1976) as an artist, sculptor, and the creator of the mobile. It was hard to believe that he was going to flip pancakes or toss a salad for us.

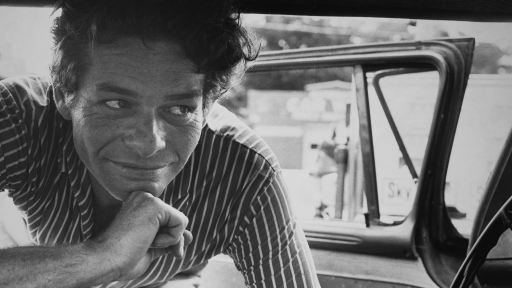

As soon as Elizabeth and I drove up to the Calder house, I saw that this would be no routine assignment. My car came to a stop in front of a typical Connecticut farmhouse, painted black. Calder was having lunch when we walked in. He was wearing a pair of jeans, a blue shirt, and heavy brown work shoes—his preferred attire for almost all occasions, I later learned. On the table was a large bottle of wine, a slab of cheese, and a loaf of coarse bread.

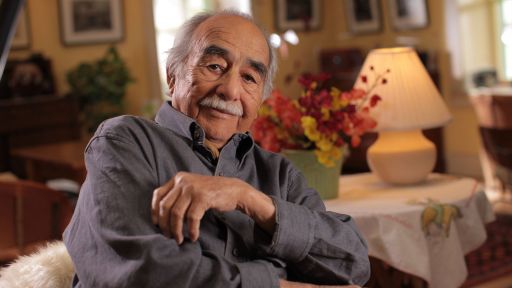

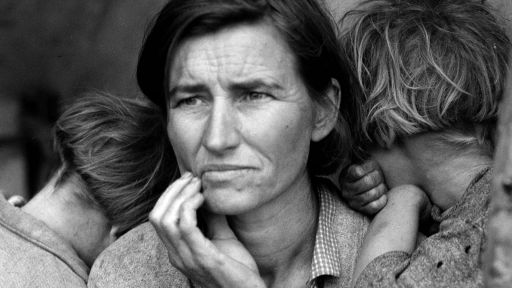

“Call me Sandy,” said Calder when we were introduced. He was sixty-four, a stout man of average height with bright blue eyes and a round face under a shock of unruly white hair. He was gracious and generous even at this first meeting.

“I think Calder had complete trust in Pedro. I think that he saw some of the photographs that he had done early on and he had great confidence in him that he would continue to make very important and really solid images that reflected on the creation of the pieces themselves.” — Joan Marter, Distinguished Professor of Art History, Rutgers University

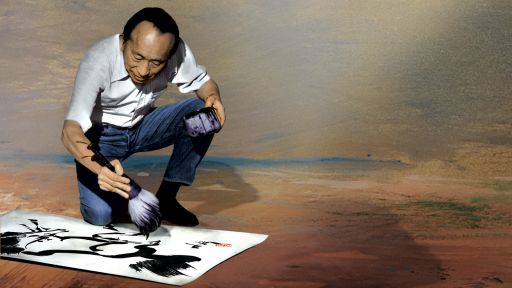

Over the years, I returned to Roxbury and Saché a number of times, a witness to the daily rituals and habits of the Calders’ life. I shot Sandy at work in his studio, lost in some creative endeavor. Starting with a coil of wire or a sheet of metal, he would begin cutting, snipping, bending, joining, and balancing, his large and pudgy hands seeming to caress the elements in which he worked. His big studio in Roxbury served him well. The studio evolved to meet his needs, although it inevitably reached a point of absolute saturation. Narrow footpaths allowed him to make his way among the anvils placed on tree trunks, large rectangular tables teeming with tools and vises, and wooden boxes that he turned into new work stations. Most helpful in navigating this welter was his habit of leaving his visor wherever he meant to begin work the next day.

The Saché studio, by contrast, served more as a storage space than a workroom. Most of his artwork there—gigantic stabiles—was manufactured by a foundry in Tours and transported to the Saché studio. The space became so overcrowded that the excess spilled outside, making a startling display on the hill.

Occasionally, I gave Sandy a progress report on my book about him. Although I did not know it, he was also at work on his autobiography. On January 15, 1965, a year after I started my book, he began dictating the story of his life to his son-in-law. Each entitled simply Calder, the two books came out just months apart in 1966, mine presenting the first two of what would total thirteen years spent documenting Sandy’s life, work, and homes.

See the Pedro E. Guerrero photo gallery for more photos.