The first time I heard the name “Helen Keller” – the first time I understood who that was and had any kind of sense of all that the name could represent – I couldn’t have been more than 10 or 12 years old. Possibly younger.

I was born with cerebral palsy and, by all accounts, I started reading early. The earliest memory I have of my lifelong love affair with books was reading a children’s bible in my pediatrician’s office. Formative flights of ecclesiastic fancy soon morphed into an obsession with superheroes and science fiction, then biographies. Whatever the subject matter of any given obsession, I couldn’t get enough. Instead of being concerned with the typical things we’ve been conditioned to associate with childhood: playgrounds, running, jumping, letting the “wild rumpus start” so to speak, my childhood was consumed by the flicker of classic black and white movies on my local UHF stations in Indianapolis, Indiana – pre-cable TV – and my beloved books, stacks of which traveled with me and since I often couldn’t decide which book I wanted to read more, there was always more than one. Since rambunctiousness of the body wasn’t the easiest option due to effort it would take and the fatigue which would later ensue, I was drawn to the unknown, unseen, unimagined worlds patiently awaiting my attention within books, and the broader world that books opened up for me at an early age.

When I started walking at the age of five after a number of surgeries, my grandmother, Katie, knew exactly how to incentivize the exercise the experts at the children’s hospital deemed necessary.

“If you walk with me to Murphy’s,” she’d say referencing the sole remaining neighborhood five-and-dime department store, “We can get a cold drink at the soda fountain and…” these were the magic words, “I’ll give you a dollar to buy some books.”

BINGO.

The destination was an AMVETS thrift store. The secondhand paradise was barely a mile away geographically speaking, but to me, AMVETS was a marvelous place where even a poor kid like me could score a paperback for a quarter, and a hardback book – if I really wanted it — for fifty cents. I would eagerly take her hand and off we’d trundle, grandma and me in search of discount riches. We’d return with a paper bag of recycled folios, new universes, and as of yet unimagined perspectives to explore.

It was during one of these forays I recall asking my grandma what HER favorite book was.

“The Story of My Life” by Helen Keller, she informed me. She’d read it as a child herself.

I’m not sure where we found the book, but I remember reading it almost one sitting on Grandma’s front porch. Unlike me, Keller wasn’t born disabled, she’d become DeafBlind at nineteen months due to illness, but something about her story resonated. And, over four decades later, it still does today.

It wasn’t until long after I’d left home to become an activist myself that I’d become aware of the social justice advocacy that led to Keller being placed on the FBI’s watchlist, her fondness for whiskey, numerous runs on vaudeville with her teacher Anne Sullivan, the fact that she missed her own film premiere because she wouldn’t cross a picket line in 1919, or that she introduced Akita dogs to the United States after a trip to Japan.

During Keller’s lifetime, which spanned nearly nine decades, it wasn’t much different.

After being celebrated as a wunderkind, in the fall of 1891, eleven-year-old Keller wrote a short story called “The Frost King” as a birthday present for one of her benefactors Michael Anagnos, who was also the Director of the Perkins School for the Blind where Keller was a student. Anagnos was so impressed he published the story in the Perkins alumni newsletter. This led to Keller being accused of plagiarism, and her teacher Anne Sullivan being labeled a fraud. Keller and Sullivan’s relationship with Anagnos was a casualty of the controversy which made national headlines, and the furor ended Keller’s association with the Perkin’s school as a student – for a while.

While eventually exonerated after much Sturm and Drang, Keller published her autobiography “The Story of My Life” in 1903 which detailed her account of the hullabaloo that ensued after “The Frost King” was published. After reading Keller’s account, author and humorist Mark Twain, who had become friendly with both Keller and Sullivan by this point, wrote a letter to Keller proclaiming his unwavering support with the following:

“It takes a thousand men to invent a telegraph or a steam engine, or a phonograph, or a telephone, or any other important thing–and the last man gets the credit and we forget the others. He added his little mite–those ninety-nine parts of all things that proceed from the intellect are plagiarisms, pure and simple; and the lesson ought to make us modest. But nothing can do that.”

They remained friends, with Keller even staying at Twain’s home on more than one occasion, until his death in 1910.

With accusations of plagiarism behind her, Keller’s fame continued to grow following the publication of her autobiography. In February 1918, Keller was asked to appear in a fictionalized version of her life, titled “Deliverance” which would use the emerging medium in an overt, unabashed attempt to illustrate the “overcoming of physical blindness and deafness as well as the deliverance from political and spiritual blindness.” Like other movies of the era, the film was high on melodrama and more fantasy than fact, but no one seemed to mind. In Hollywood then, and perhaps now, that was the norm rather than the exception.

While visiting California, Keller and Sullivan had the opportunity meet with Hollywood notables including Charlie Chaplin. Keller recalled later, “he let me touch his clothes, his shoes, his moustache so that I might have a clearer idea of him onscreen. He sat beside me and asked me again and again if I was really interested–if I liked him and the little dog in the picture.”

Helen Keller, Anne Sullivan and Polly Thomson meet Charlie Chaplin during the filming of “Deliverance” (1918).

Reportedly, Chaplin was already familiar with American Sign Language by the time he met Keller which, if true, made their historic meeting easier and, if one believes in such things, almost inevitable. Chaplin was friends with Deaf actor Granville Redmond who reportedly taught the silent film icon finger-spelling, pantomime routines, and helped him hone the silent communication skills Chaplin went on to showcase with his little tramp character. Chaplin, in turn, hired Redmond to act in several of his films including “A Dog’s Life.”

While Helen certainly achieved fame, she found fortune more difficult to obtain. The New York Call newspaper described one defining moment which, in hindsight, offers at least a partial explanation:

On August 18th, 1919, Helen Keller took part in a strike called by Actor’s Equity—joining the picket line against the debut of the silent film “Deliverance,” about her own life. Not only did she join in the picket line, she spoke at the union’s strike meetings in support of their dispute with management regarding their wages. She declared she would “rather have the film fail than aid the managers in their contest with the players.”

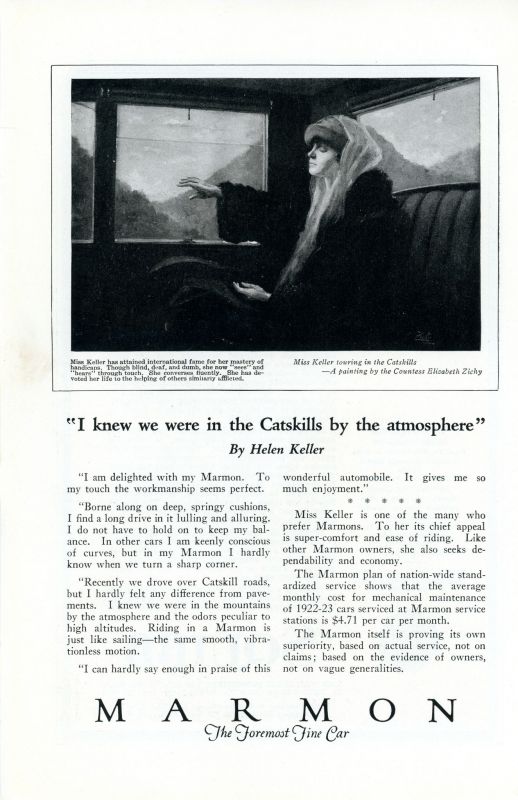

Helen and Anne remained in the spotlight, however, by touring the vaudeville circuit and using Keller’s unique perspective to sell the ineffable. Examples abound, but my personal favorite is an advertisement for Marmon automobiles that I stumbled across in an issue of National Geographic from 1925, while researching her life for a film project I did with Turner Classic Movies.

In the ad, the copy attributed to Keller gushes:

“Recently we drove over Catskill roads, but I hardly felt any difference from pavements. I knew we were in the mountains by the atmosphere and the odors peculiar to high altitudes. Riding in a Marmon is just like sailing—the same smooth vibrationless motion.”

Marmon’s use of a DeafBlind woman as their celebrity spokesperson and the advertisement’s clever subversion of what is traditionally perceived as a handicap re-frames Keller not as superhuman, but rather as someone absolutely in charge, possessing an agency unique to her lived experience. The ultimate authority in a reality non-disabled people routinely take for granted.

So, here we are, nearly a century later leading some to ask: What lessons can Helen Keller teach us today? Why are we still making movies, and writing articles about her? Willfully ignorant internet lemmings consider Keller a hoax, after all.

To them I offer Keller’s own words:

“There is nothing more beautiful than the evanescent fleeting images and sentiments presented by a language one is just becoming familiar with—ideas that flit across the mental sky, shaped and tinted by capricious fancy.”

The march of time can lead one to forget the feeling of newness we had as children and become jaded by the cynicism around us, but within that harsh truth also lies a kind of liberation. If we can resist the compulsion to shut down, close off and tune out, perhaps the enduring legacy of Helen Keller reminds and beckons us to remember the freedom that comes from consciously sailing toward the maelstrom and welcoming the unfamiliar treasures that we discover there.

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Elsa Sjunneson: DeafBlind author [Audio Description + ASL]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2022/03/Rxaa3o7-asset-mezzanine-16x9-JNz2pke-512x288.jpg)

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Helen Keller studied socialism [Audio Description]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2021/10/EqPyQ19-asset-mezzanine-16x9-tGsOsJd-512x288.jpg)

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Helen Keller the suffragist [Audio Description]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2021/10/yTaS3yJ-asset-mezzanine-16x9-4nbxXU4-512x288.jpg)

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Keller's use of oral communication [Audio Description]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2021/10/dUfOBIW-asset-mezzanine-16x9-NlZMY6w-512x288.jpg)