Amanda Kim, director of American Masters: Nam June Paik – Moon is the Oldest TV, shares her journey to discovering Nam June Paik as an artist and authentically telling his story in this conversation with writer Carlos Valladares.

Q: Describe your first encounter with Nam June Paik, as a name or as an artist.

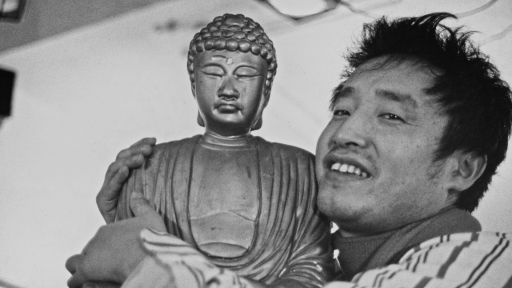

Well, Nam June is a national treasure in Korea. He’s Korea’s most famous artist. And I remember hearing of his name at an extremely young age. My mom went to art school, and my dad would take me to museums where I saw his work. I’d always known about him; he’d always lingered in the subconscious. Then, about six years ago, when I started seriously researching him, I saw [his 1974 video sculpture] “TV Buddha.” To this day, it’s one of my favorite works of art. I remember thinking: “Wow, this is so ahead of its time. I’m curious what others thought of it…” I explicitly connected him to the history of Korea. I’ve always been superstitious and interested in alternative histories of spirituality, so that was the initial spark: his own relationship to Korean spirituality, this kind of ancient form of shamanism in Korea.

After a while, I’d compiled a lot of niche information on Paik, the stuff you wouldn’t find in museums or even old catalogs. Then I talked to my friend David Koh, who is a producer on this film and has produced many other documentaries, and I said to him: “Nam June is so interesting, why isn’t there a documentary about him? I’ve uncovered so much in just my own research.” And David said, “Oh, that’s my bucket-list project. We should make a treatment.”

Q: And I heard you mention that David Koh [one of the producers] also worked alongside Nam June Paik at one point?

Yes! So when I told him about my research, he said: “I was Nam June’s assistant when I was attending college in New York.” He knew him personally. And David said that Nam June just worked on a different plane. He let things happen. Chance operations. Nam June was so nice to everyone he met, and he thought that every encounter was a karmic relationship. So even if he just sat next to a few strangers on a train, or bumped into a lady while walking down Sixth Avenue, that meant something.

Q: How did you get into filmmaking, specifically documentary?

I started production work at VICE. I studied comparative literature and had no experience in filmmaking and production. But I joined VICE and started making short branded content. VICE was very early in the branded content space. They were incorporating brands into these short-form documentaries that VICE was doing anyway, and having the brand pay for it. Then I moved over to TV: Viceland. I was a producer there, developed pilots, managed teams. So that’s where I got my experience in production. But I hadn’t made any narrative work. This is my first feature. I produced a short that was at Sundance in 2020, which was fiction. So I had experience in documentary because of VICE.

Q: Who were some of your influences or inspirations for the making of the film?

Well, “F for Fake” is one of my favorite documentaries. And I love [Orson] Welles’s sense of humor, and the style of “F For Fake.” Maintaining a funny touch was crucial to me for my film. He doesn’t take himself too seriously, which isn’t always a guarantee in the art world.

Q: Was there a specific political or aesthetic urgency — within the art world, or the global sphere — that invested your spirit as you made the film?

In the middle of editing the film, the Russia-Ukraine War broke out. And a lot of everything Nam June was experiencing was related to the Cold War, why he left his home, had fresher significance. But on the whole, for me, the great political aspects were not necessarily contained in current events, but in historic ones. I was interested in learning more about my Korean roots, the Korean War, the Japanese occupation and how that informed Nam June’s interest in why communication is so important and how we can transcend language. His thesis was that you don’t have to speak the same literal language as another in order to communicate and connect with them. Video is another way of communication. It’s not Korean, or Japanese, or German.

Q: You describe [Paik] also as something of a “Nostradamus of our present,” that he was prescient in a scarily accurate way.

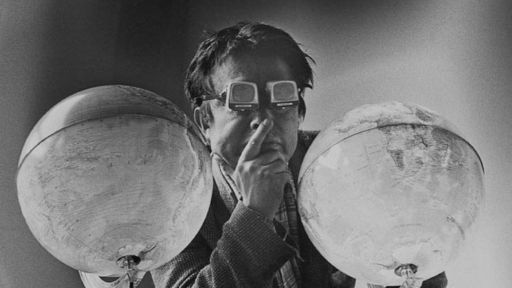

I think people are prescient when they have a macro view of the world. Nam June was not just interested in making art, hermetically sealed. He constantly read the newspaper, he kept up on the latest in technology, the stock market, the business sections. The Fluxus ideology reflects this: Life is art, and art life. And the personal and the artistic, with Nam June, are realms that are so intertwined, so cohesive. Inseparable. Nam June was seeing patterns, and knew where we were heading, and I hope the film, like Nam June’s art, can instill a critical sense in the viewer, questioning the latest iPhone instead of blindly buying it.

Q: I love, too, how much he approaches the world through a very optimistic lens, which is unique and rare, not just then, but today.

I really love that interpretation. Because that’s actually why Nam June is inspirational to me, personally. He knew so much, and he could always see the dark side of things, and saw the gray areas. But he also saw possibility. That’s what I hope people take away from the film: no matter how glum things get, no matter how much we seem unable to break the cycles of history, we should always be thinking about greater possibilities and potentialities.

Q: What parts of Paik’s life did you become interested with or enamored by?

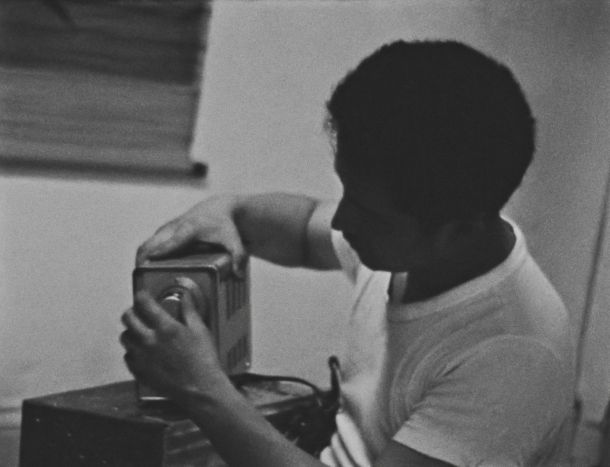

I was so interested in his early life, when much of his psyche was developed. The first act, at one point, was nearly an hour long; there was so much interesting detail. But he doesn’t get to video until way later in his life. It’s not the medium that defines him — it’s cool that he’s the father of video art — but that wasn’t a concern of his to be just known as a video artist. He also did sculpture installations and music performance. And he continued to do all of those things around the video art. And as a result, he’s so hard to define.

Q: It’s fascinating to see how paths cross in the New York art world — for instance, the New York Times music critic who pans his ‘60s “Cageian” performances, but then later unexpectedly becomes Paik’s biggest patron and an intimate of his when he’s getting into video art.

It speaks to his openness. One can make enemies of these critics, but he befriended a lot of them. It’s his idea of him not trying to create division or boundaries between people. He’s not like Jesus or anything, but he made an effort to be conscious of any bias that we grew up with or socialized.

Q: How did your knowledge expand with regards to Nam June Paik’s friends whom you interviewed?

They gave a more colorful, rounded experience of what it was like to be in Nam June’s presence. But it was tough going at first, just to even get to them, technologically speaking! We started filming at the height of COVID-19. We wanted to continue production, and thought it was very in the vein of Nam June to incorporate iPhone footage, more affordable cameras, Zooms. We thought it would be cool, also, to mix high-res and low-res formats, which is part of the style, but also a reflection of the archival material we had to work with. It’s not like [Todd Haynes’s] The Velvet Underground doc where everything is 16mm, 8mm, pristine film and looks gorgeous. Here, it’s splotchy, different aspect ratios, some parts were more pixelated than others.

Q: Yes. It feels apt to Paik’s sensibility.

Sometimes we leaned in to how bad the master looked, because to my eye it does look great, because it honestly reflects the era, the limitations and possibilities of the technologies of the time.

Q: And it democratizes what a “good image” is. So many filmmakers nowadays are disastrously taken up with this compulsion to use a digital image that’s clean, pristine, perfectly rendered. But there is unfathomable beauty in the image that looks like it’s still loading: look at what is accomplished in the latest films of Hong Sang-soo, for instance.

For sure. And I think that part of Nam June’s whole thing is humanizing technology. He understands that this technology will become more and more advanced, but the important thing to understand is how this technology can serve and benefit humanity, not take over and become this cold machinic thing that destroys humanity. That, in itself, in the image, is felt. When you see the glitch or see how broken-down the image is, you feel the human touch.

Q: I think that’s touched on in particular in the section where you cover “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” how everything is collapsing. Nothing is working technology-wise, but Nam June is calm about it all and says, “That’s exactly what we want!”

“I just let it happen!”

Q: I love that you have Steven Yeun narrating so much of Nam June’s own writings.

I thought it was kind of reminiscent of Nam June’s artworks, too. Nam June had this guy named Russell Connor who would narrate a lot of Nam June’s stuff, he was Nam June’s voice. That was one of the things that I thought was interesting and meta: Steven is doing what Nam June himself would have done in a “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell”-type situation. And I also liked that Steven felt this really strong connection to Nam June’s story, and so I felt that the emotion and the body of Nam June was evoked. You can feel Steven’s connection, and I liked that.

Q: What was your biggest challenge when making the film?

With documentary, you never know what’s going to happen, like Nam June’s ethos! With fiction, too. My partner makes fiction, and I can see there’s a million things that can go wrong, so you have to be really open to the process. If you’re doing cinema verité, for instance, following a subject, you have no idea where that story might take you. It’s also the same with archival film. You have what exists, and you have to be so open to the process, and you’re finding a lot of the story in the edit. And so, being OK to the unknown—which is hard for people like myself, who like to have more control over things.

Q: He was working in a particular time I guess when the technologies that are so ubiquitous to us now weren’t ubiquitous. He’s very optimistic about technology, but from today’s vantage point, there’s so much to be cynical [about]. Social media, Elon Musk, what Silicon Valley has become. So how do you reconcile these two strands when you’re making the film: the cynicism towards technology and the optimism towards its possibility?

Whenever I saw Nam June’s work in a museum show, I always thought there was a kind of blind optimism towards technology. But making the film I realized that I think he’s hopeful, yes, but there’s an undeniable cynicism, too. Ultimately, he’s always questioning the latest thing. Creating that satellite show was not just, “This is new and amazing technology, let me use it, because it’s only going to do good.” He saw what was happening during the Cold War, and he said, “How can we use this for good?” It doesn’t have to just be a weapon, it can be a connector. That’s what interests me. And I hope that the viewer will become a bit more critical, to question where we are today about how we’re using our technologies. Is there a better way? And not to be simply excited about the latest gadget.