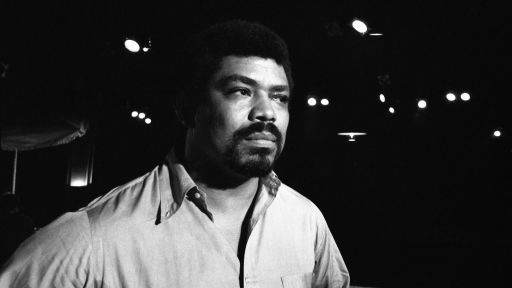

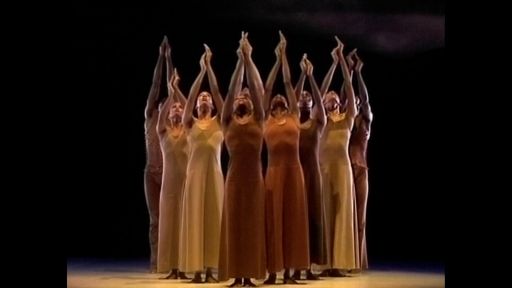

Acclaimed hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris honors the legacy of Alvin Ailey with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s first two-act ballet, “Lazarus” – a trilogy including Harris’ past work “Exodus” and “Home,” as well as an hour-long original piece inspired by the life of Ailey. Through “Lazarus,” Harris addresses America’s racial inequities both past and present, connecting Ailey’s own “blood memories” to modern day.

1. Alvin Ailey founded his company back in 1958. Why does his work still resonate so much today?

Mr. Ailey’s work is timeless. This is the brilliance of his vision. He had the ability to see beyond the trend of the day. He saw the sincerity of the work, the heart and spirit of the work if you will. I’ve found sincerity to be the key to creating meaningful work. Mr. Ailey’s ability to move audiences and speak to them on both an emotional and spiritual level is unmatched. Specifically, he spoke to the plight of African Americans which continues to resonate today. In addition, his choreography allows the Black dancing body to confront colonization, exclusion and its so-called boundaries. This is more than evident in his work, his vision and core values.

2. How has the legacy of Alvin Ailey inspired the work you do?

Not to be redundant, but it’s the timelessness of Mr. Ailey’s work that pushes through time itself. His work not only addressed the issues of African Americans but also challenged the political, economical and social reality of each era. What’s also inspiring to me is his well oiled machine (infrastructure) of the Ailey company and its brand. The fact that the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is still here, still relevant, is a testament not only to Ailey’s vision but also to his determination and spirit. As a Black man, I’ve been especially inspired by Mr. Ailey’s tenacity in the face of racism and discrimination to persevere.

3. In the process of making “Lazarus” for the 60th anniversary of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, what is something new that you learned?

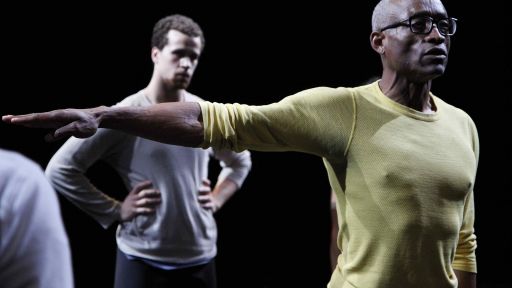

What I learned about Mr. Ailey was that like many of us he was searching for unconditional acceptance, love, and understanding. You could see it in his body language and tone in interviews. His eyes were often sad and “yearning” for lack of a better word to describe what I saw and felt in his eyes. What I learned about myself was that I had an actual process. It wasn’t until choreographing “Lazarus” that I realized not adhering to a process was actually having a process and that it was impossible to not have a process. For years, I never did any preparation or thinking about a work I wanted to create. I simply went into the studio and began creating vocabulary, then movement phrases, blocking and staging, and then I added the story, narrative, or through line last. However, this time I was forced to approach the work differently. I was invited to choreograph the work a year prior to the premiere; this gave me enough cushion-time to dive into this work in a completely different way. What most don’t know is at the time I was invited by Robert Battle to set work on Alvin Ailey I was suffering from severe arthritis in both hips and could barely walk let alone dance. Naturally I didn’t want to miss the opportunity of a lifetime, so I accepted the invitation and began writing down every thought and idea around music, production, and choreography. When it came to being in the studio and creating the work I hired an alumni of Rennie Harris Puremovement, Nina Flagg, to be the rehearsal director and an alumni student of mine from the University of Colorado, Millie Heckler, to be our assistant. Both Nina and Millie were familiar with my terminology, dance style, and rhythm sequences. In addition, I hired a “skeleton” crew of street dancers from New York to rehearse 2 to 3 hours prior to rehearsing with the Ailey dancers. I basically choreographed from the chair. This changed not only my perspective, but my process. Suffice to say, it made me realize I had a process; being forced to write my ideas down gave me a new perspective on creation.

4. Why is hip-hop such a powerful form of cultural expression?

Hip-hop culture is the voice of several generations now. It’s no different than rhythm and blues/rock ‘n’ roll, jazz, bebop, soul and funk music that predate it. It’s not a phenomenon or an anomaly; it’s doing what every new genre of music does and that is speak on the frequency of the generation born of it. Most importantly, music, such as the genres I listed above, reminds that generation that they are free, they have a voice, and have choice. The word “hip” derives from the word hippi (wolof) which according to Dr. Geneva Smitherman (Black Talk), means to open your eyes (*re-open your eyes), to be aware. Per my own research, the word “hop” suggests jump, lift, up, elevation, suggesting something otherworldly or god if you will. In my opinion, hip-hop is a modern day religion and it simply means to be aware of something greater than oneself. The core of hip-hop is made up of five elements that govern its expression: MC’ing, DJ’ing, Graffiti, Breaking, and Knowledge. Knowledge is knowledge of everything. It suggests that the culture is unlimited and that everything human and beyond falls under hip-hop culture.

5. What kind of unique impact do you think dance can have on society?

In my opinion, dance is the most dangerous of all the expressions. It’s the one thing that unites folk in the same space physically. What I mean is movement and rhythm binds folk to an unseen force and when engaged can change reality. Remember, most define dance as following a set of sequenced steps. Therefore, to literally march in protest is an expression of dance. To work collectively to build a building is a form of dance. Dance movement changes reality as we know it.