In 2001, when I was producing and directing American Masters—Quincy Jones: In the Pocket, Quincy was writing his autobiography. He told me it was the toughest thing he had ever done.

This came from a guy who produced a film with Steven Spielberg, the best-selling album of all time with Michael Jackson, an anthem called “We Are the World” that raised more than 63 million dollars for humanitarian aid, a Presidential Inauguration and a Hip Hop Summit, along with so many other landmark events.

In an interview, Oprah Winfrey said, “I think that Quincy on a bad day does more than most people do in a lifetime.”

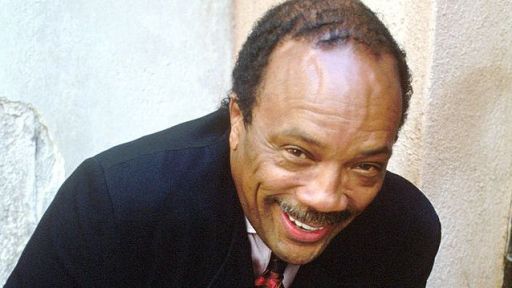

So 22 years after making the film, as Quincy celebrates his 90th birthday, it seems like a good time to try to remember what I learned from him.

https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/archive/interview/quincy-jones-interview-1/

Part of what makes Quincy a “man among men” is his ability to walk with kings, but not lose the common touch.

Quincy is equally at home with royalty as he was on the south side of Chicago, where he grew up during the Great Depression. It was also in Chicago where Quincy lost his mother:

They took my mother away to a mental institution when we were very young kids. . . The kids used to tell us, ‘you’d better be careful ‘cause when your momma gets out, she’s gonna kill you.’ One time we saw when she was out, she yelled out to us, probably trying to see us. We screamed and just ran on down the street.

When I once asked Quincy, “What is music to you?” he said plainly, “My mother.”

At the age of 10, his father (a carpenter—to this day Quincy still keeps his old saw next to his piano) moved the family to Seattle.

We only had radio then . . . it stimulated our imagination, because we could imagine everything, that the Shadow and the Green Hornet and all those people were Black. . . When the big bands came through Seattle and I was 12 and 13, I saw this body of unified Black men playing in 16-piece bands, playing with this worldliness and dignity and pride and form. I turned from a thug to a musician.

The moment of truth came after a night in which Quincy and his friends robbed some grocery stores and broke into an Armory, discovering a canteen stocked with lemon meringue pies and ice cream. After they ate all the ice cream and had a massive food fight, they broke into another room, which had an upright piano in the corner.

I touched that piano, and my life was different ever since. It was over. I knew then inside something happened electrically… That was what I wanted to do all my life.

Quincy learned trumpet, ran away with a band and recorded his first song at the age of 18. He was accepted to music school, dropped out, went to Paris in the early 60s and studied with the greatest music mentor of the 20th century, Nadia Boulanger—teacher of Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein. He learned to arrange music.

Of course, it makes sense to me that at the age of 22, Quincy would be recruited by Dizzy Gillespie to lead a band on a U.S. State Department “Jazz Ambassador” tour to the Middle East, where Quincy and his friends wrote arrangements for the national anthems of every country they visited, starting with Iran. Then Quincy conducts Count Basie’s Orchestra for Frank Sinatra (“Fly Me to the Moon”), becomes the first Black executive at a record company (Mercury), breaks into scoring Hollywood movies thanks to Henry Mancini and Sidney Lumet (who hired him for his first score on “The Pawnbroker,” produced by my late father-in-law, Ely Landau), earns 80 Grammy nominations and wins 28 of them, and brings out the best in people like Oprah Winfrey, Will Smith and musical genius Jacob Collier (whom he discovered on YouTube). His lesson to aspiring young talents is “be ready for the call,” but what stays with me is what the late great singer James Ingram said when I asked him for Quincy’s secret. He told me, “You gotta stay hungry.”

https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/archive/interview/herbie-hancock/

No matter the success, Quincy’s common touch remains, maybe born out of his difficult childhood and his search for love and belonging.

Early in his career, Frank Sinatra gave him a nickname, “Q,” and Quincy often invents his own affectionate nicknames for his colleagues. He called his buddy Ray Charles “Six-Nine”; songwriter Rod Temperton was called “Worms.”

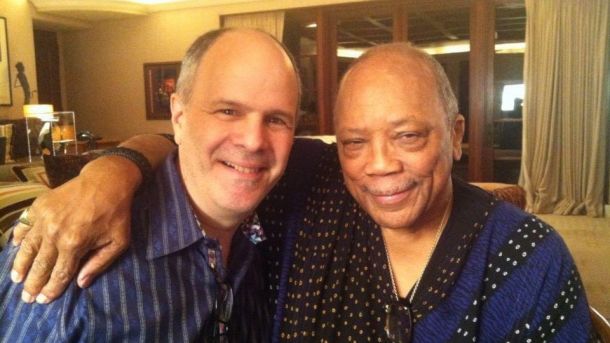

When we created Quincy Jones: In the Pocket, he started calling me “Work Junkie.” From a man who does more on a bad day than most do in a lifetime, I took my nickname as a supreme compliment. When his autobiography came out, Quincy inscribed a copy to me with the following message:

I feel blessed to have you in my life & in my heart. Thank you for your profound & consummate “Junkie” professionalism- (it takes a junkie to know one!). Seriously Mike, I loved every minute in it with you & the frosting on the cake is our cherished friendship. I love you. Quincy ♡

Happy 90th Birthday, Quincy—I love you too, and hope your next 90 years are equally fulfilling.