1953: Rita Moreno arriving at the premiere of ‘Lili’. (Photo by M. Garrett/Murray Garrett/Getty Images)

“Esa es Rita Moreno. La nuestra,” said my maternal grandmother Ada Loubriel into the cassette recorder. It was 1976, and I, a precocious 10-year-old documentarian, was recording my family watching a dubbed Spanish version of “West Side Story” on TV in the Puerto Rican urbanización of San Gerardo.

For many Puerto Ricans like my grandmother, Rita Moreno was one of the most visible parts of the collective self, a part that we were proud of and made us proud. The sole Puerto Rican woman to become a movie star in Hollywood’s Golden Age, and the only one to have earned all of the entertainment industry’s top recognitions—Oscar, Tony, Emmy (two), and Grammy, Moreno signified the victory of Puerto Ricans over colonialism, poverty, and racism. As Moreno recalls in her book, “Rita Moreno, A Memoir,” “While the Oscars were being televised, there was a sacred silence in El Barrio—Spanish Harlem—and in all of the other Puerto Rican neighborhoods in New York…And what an outcry when I won! People were literally hanging out their windows, yelling, ‘She won!’ She won! She did it. What they were really saying was ‘We won!’” Her rise from a wooden cottage in the small rural town of Juncos to an elite global stage verified our worth and asserted our potential as human beings and as Puerto Ricans.

Equally important, it was not a one-way affair. Moreno loved Puerto Rico back and used every significant opportunity to say so. A particularly emotional instance took place in 1975. After receiving a Tony award for her performance in “The Ritz,” she beamed: “Rita Moreno is thrilled. But Rosa Dolores Alverio from Humacao, Puerto Rico is undone!” Her triumph was for and about Puerto Ricans.

Fittingly, Moreno has had an outsized influence on Puerto Rican women dreaming of careers in film and television, industries that since their founding have consistently offered Latinas limited, stereotypical, and demeaning roles as beautiful señoritas, Latin sexpots, and gang girls. Jennifer Lopez, the only Puerto Rican woman superstar in Hollywood history, summed up her predecessor’s importance in a speech accepting the 2014 GLADD Vanguard Award from Moreno: “Her [Moreno’s] performance in it [“West Side Story”] had more impact on me than anything else when I was young, on my artistic life, my career path, and ultimately, my confidence . . . Watching this beautiful, strong, Puerto Rican woman command the screen with her talent at a time when Latina women did not have every door in this industry open to them . . . made me feel worthy.”

Although Lopez has reached unprecedented prominence, Moreno’s iconic status shows no sign of diminishing. Her enduring relevance is evident when the then 31-year-old star of Jane the Virgin, Gina Rodriguez, offered a love letter to Moreno—one of her co-stars—during the 2015 Kennedy Awards. In her two-minute address, Rodriguez tearfully declared: “A fifteen-year-old girl from Chicago who had never seen a Puerto Rican represented once asked her mother. Mom, when did Puerto Ricans come about?… I never see us in my favorite TV shows or movies. We must not have existed back then, right? And then she introduced me to you…And I just wanted to be just like Rita. You gave me hope, you gave me a reason to fight, to speak up, you gave me a voice.”

Of course, not every Puerto Rican feels the same way, at least not always. For some scholars and activists, Moreno represents a complex challenge. The educator Blanca Vázquez wrote on how she felt as a teenager watching Moreno sing denigrating lines about Puerto Rico such as “let it sink back in the ocean” in “West Side Story’s” “America” number, “I remember seeing it and being ashamed.” Most recently, Moreno became the object of criticism after she defended Lin Manuel-Miranda’s “In the Heights” film adaptation, which many Latinxs panned for its colorism in the representation of a Dominican-majority community. To Moreno’s quip to critics – “can’t you just wait a while and leave it alone?” – a part of Latinx Twitter lashed back. “Sorry, I love Rita Moreno but her attitude is exactly what needs to be addressed,” wrote journalist Arturo Domínguez.

Moreno immediately apologized for her remarks, stating that she had disappointed herself by being “dismissive of black lives that matter in our Latin community.” It is however, revealing that throughout the media maelstrom, Moreno still inspired respect from her critics. As journalist Theresa Braine put it, “Moreno received social media clapback over her statements, though all came with accolades for the trail she had blazed over a 70-year career.” This is because what makes Moreno a star to her fans goes beyond Hollywood fame. Many recognize that Moreno’s value not only lies in her luminous craft as an actress, singer, or dancer. It also encompasses two other no less critical dimensions: her decades-long fight to enjoy a dignified career as a Latina in Hollywood, and her gifts of transformation, which can turn stereotypical roles into meaningful characters, and colonial harm into insurgent praxis. Like few other performers in Hollywood history, nothing is the same after Moreno leaves the stage, and something else is possible.

The best-known example is Moreno’s portrayal of Anita in “West Side Story.” In this film, for which she became the first Latina to win an Academy Award for best-supporting actress, Moreno played the quintessential sexy Latin spitfire in brown-face and with an outlandish accent. As noted by Vázquez, Anita also had the burden of voicing disdain for Puerto Rico. Yet, that the role demanded Moreno to display “the full force of her talent” as an actress, singer, and dancer allowed her to show a degree of excellence that far exceeded generalized assumptions of what Latinas were capable of achieving. By embodying Anita as a “real Puerto Rican” who “stood up for herself” Moreno similarly infused the character with ferocity and force. Fittingly, even as she was performing a stereotype, Moreno put it in question by “executing” her role so extraordinarily well that she killed it. Step by step, line by line, Moreno’s Anita proved that Puerto Ricans and other Latinos were neither “bad” people nor less talented than others. Instead, to paraphrase Jessica Rabbit, they were only written that way.

Still, Moreno’s initial approach to survive Hollywood by breathing life into stereotypes turned out to be personally costly. After “West Side Story’s” enormous success and receiving the industry’s highest honor did not change the type of roles that the studios offered her, Moreno made a consequential choice: to refuse. Instead of accepting the even more trite “gang” and B-movie roles that continued to come her way, she started to use all available opportunities to disrupt stereotyped knowledge with creativity, honesty, and wit.

In quick succession, Moreno developed the Tony-award-winning character of Googie Gomez, which appeared in both the Broadway (1975) and film versions of “The Ritz” (1976). Through Googie, Moreno aimed to expose and unsettle the toxic ridiculousness of Latina stereotypes. In Moreno’s words, “‘By playing Googie, I’m thumbing my nose at all those Hollywood writers responsible for lines like ‘Yankee peeg, you rape my seester, I keel you!'” In addition to conceiving Googie, Moreno became a regular cast member in The Electric Company, a children’s educational series that ran on PBS from 1971 to 1977. Going against her agent’s view that performing in the show would signal that she was “out of work,” Moreno saw it as a precious opportunity. Through the series, Moreno would contribute to not only teach a new generation the value of reading but also of racial diversity, gender equity, and social justice: “I have to do it…. It’s doing everything that’s great, and noble, and fine.”

In her post-“West Side Story” work, Moreno’s presence did more than increase Latina media representation, as crucial as this was. She likewise demonstrated the capacity of Puerto Rican performers to fashion novel forms of language, performance, and communication which were generally unavailable on American screens. As playwright Charles Ludlam once said about queer Puerto Rican performers of the 1960s, Moreno “knew she was Puerto Rican and used it.” This is clear in most of her appearances, including the bilingual “Muppet Show“ music sketch “Fever!” whose artistry Moreno described as “a fury of Puerto Rican sensuality and rage…” and in Googie Gomez, which Moreno dubbed a “crazy Puerto Rican” of “my creation.”

Moreno is then as much a part of Hollywood history as a precursor to the Puerto Rican cultural movements that emerged in the late 1960s. Deploying her knowledge of multiple linguistic codes and her experience of growing up poor, female, and brown, Moreno uses Spanish, Puerto Rican expressions, and accented English to open up new meanings and compel English to tell different stories. For instance, Googie’s claim to her backup dancers that, “My career is no joke”—pronouncing “joke” as “yoke”—prompts a reflection on the vexed history of Latinxs in Hollywood. At the same time, Moreno’s wordplay and award-winning performance underscores the power of Latinxs to turn a yoke into laughter, underlining that joy rather than profit or dominance is the ultimate reason to act.

No less important, Moreno incorporated a biting critique of the sexism and racism of the industry into her star persona, rarely wasting an opportunity to challenge it in interviews and other public appearances. As Moreno once stated: “Like many aspiring actresses, I came to Hollywood wanting nothing more than to be the next Lana Turner, but my education was to be abrupt and painful…Latino contract players were afforded no options in the old studio system; we played the roles we were given no matter how demeaning they might have been.”

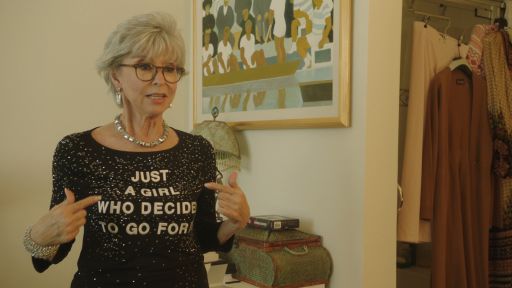

For Moreno, the price of her defiance may have been the industry’s containment to character and supporting rather than A-list roles. Not even her EGOTs reward a conventional lead. This realization begs the haunting question of what else could Moreno have created if she had not faced such relentless racism and sexism. But Moreno’s strategy to, like Googie, believe in herself and stare stereotypes down has allowed her to remain a star for an unprecedented seven decades, well into her eighties, and in the process redefine the meaning of stardom for Latinas.

Rita is then “la nuestra” not only because she came from Puerto Rico but also because of how she fought, loved, and thrived in the midst of formidable obstacles. Which is also why Rita is more than our star. Her legacy belongs to everyone determined to bring different worlds into being.