Proving that Robert Capa’s “Falling Soldier” is Genuine: A Detective Story

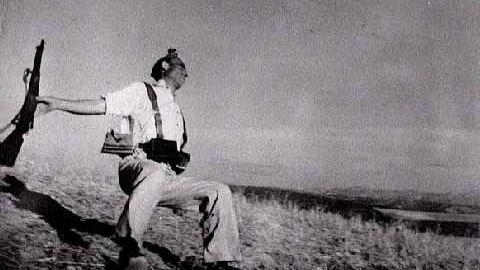

When I began the research for my biography of Robert Capa, in 1980, one problem I inherited was that of dealing with an allegation of fakery regarding Capa’s 1936 photograph of a Spanish Republican (Loyalist) militiaman collapsing into death, the so-called Falling Soldier. (Its proper title is Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936.In this article the photograph will be referred to as The Fal ling Soldier;the man in the photograph, when not referred to by his name, will be called the Falling Soldier [intentionally not italicized].) The picture is one of Capa’s two most famous (the other being of a GI landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day), and it has often been hailed as the greatest war photograph of all time.

The allegation had first surfaced in 1975, in a book by Phillip Knightley, a British journalist and historian, about how war correspondents — ever since the beginning of the profession, during the Crimean War of the 1850s — had often distorted the truth.

The allegation had first surfaced in 1975, in a book by Phillip Knightley, a British journalist and historian, about how war correspondents — ever since the beginning of the profession, during the Crimean War of the 1850s — had often distorted the truth.

Very little concrete information existed about Capa’s photograph. In August 1936, a few weeks after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Capa went to Spain with Gerda Taro (his lover, and herself a tyro photo-journalist) to cover the Republican government’s resistance to General Francisco Franco’s fascist rebels. The Falling Soldier was first published in the September 23, 1936, issue of the French magazine Vu (below), where it was reproduced with another, similar picture on the same page. The sub-head on the top of the page reads, “How they fell,” but there is no mention of where or under what circumstances the pictures had been shot. The stirring text reads, “With lively step, breasting the wind, clenching their rifles, they ran down the slope covered with thick stubble. Suddenly their soaring was interrupted, a bullet whistled — a fratricidal bullet — and their blood was drunk by their native soil.”

Some writers have claimed that both The Falling Soldier and the photograph published in Vu directly below it — showing a man in a further state of collapse — show the same man. Careful examination, however, leaves no doubt that they show two different men who fell on almost precisely the same spot. (The configurations of prominently upstanding stalks of grass in the two pictures are identical.) The Falling Soldier (below left) is wearing a white shirt and what appear to be khaki trousers; from each shoulder a strap runs straight down to a cartridge box at his waist; and he flings his gun away as he falls. The man in the other photograph (below right) is wearing a one-piece boiler suit; the straps running from his shoulders to his cartridge boxes cross at the center of his chest; and he seems to hold his gun firmly as his arm twists behind his back. Another photograph (above) shows the two men lined up with some of their comrades and waving their rifles. The man who was to become the Falling Soldier appears at the far left; the other is the third from the left.

Some writers have claimed that both The Falling Soldier and the photograph published in Vu directly below it — showing a man in a further state of collapse — show the same man. Careful examination, however, leaves no doubt that they show two different men who fell on almost precisely the same spot. (The configurations of prominently upstanding stalks of grass in the two pictures are identical.) The Falling Soldier (below left) is wearing a white shirt and what appear to be khaki trousers; from each shoulder a strap runs straight down to a cartridge box at his waist; and he flings his gun away as he falls. The man in the other photograph (below right) is wearing a one-piece boiler suit; the straps running from his shoulders to his cartridge boxes cross at the center of his chest; and he seems to hold his gun firmly as his arm twists behind his back. Another photograph (above) shows the two men lined up with some of their comrades and waving their rifles. The man who was to become the Falling Soldier appears at the far left; the other is the third from the left.

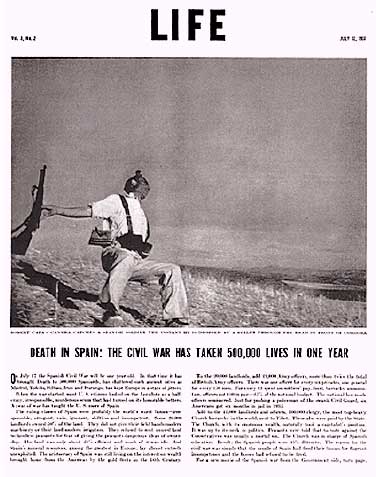

When The Falling Soldier was published in the July 12, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the caption stated, “Robert Capa’s camera catches a Spanish soldier the instant he is dropped by a bullet through the head in front of Córdoba.” Over the following years and decades, during and after Capa’s death, the photograph was widely published without any questions ever being raised about its reliability as an unposed document.

When The Falling Soldier was published in the July 12, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the caption stated, “Robert Capa’s camera catches a Spanish soldier the instant he is dropped by a bullet through the head in front of Córdoba.” Over the following years and decades, during and after Capa’s death, the photograph was widely published without any questions ever being raised about its reliability as an unposed document.

The allegation that Capa had posed his photograph was first made by O.D. Gallagher, a South African-born journalist, who, as a correspondent for the London Daily Express,had covered the Spanish Civil War, at first from the Nationalist (Franco) side and later from the Republican. Gallagher told Phillip Knightley — who published the story in his book The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam; The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth Maker (1975) — that “at one stage of the war he and Capa were sharing a hotel room.” (Knightley does not tell us where or when during the war Gallagher had shared a room with Capa.) Gallagher told Knightley that at that time “there had been little action for several days, and Capa and others complained to the Republican officers that he could not get any pictures. Finally . . . a Republican officer told them he would detail some troops to go withCapa to some trenches nearby, and they would stage some manoeuvres for them to photograph.”

In 1978 Jorge Lewinski published in his book The Camera at War his own interview with O.D. Gallagher, in which the journalist claimed that Franco’s troops, not Republican ones, had staged the maneuvers. The glaring inconsistencies in Gallagher’s accounts to Knightley and Lewinski should have discredited his testimony, thereby ending the controversy immediately.

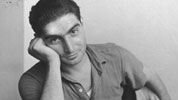

In any case, it is possible to document Capa’s travels in Spain between the outbreak of the civil war and the first publication of his photograph; he was never anywhere within several hundred miles of San Sebastián. Gallagher probably did share a room near San Sebastián with a photographer who made pictures of posed exercises, but that photographer was certainly not Capa. Nearly forty years after the events, Gallagher’s memory had clearly played a trick on him. No doubt in perfectly good faith he confused Capa with someone else with whom he had shared a hotel room there in 1936. There is no evidence that Gallagher and Capa ever met before January 1939, when they were both staying in the Hotel Majestic in Barcelona. On the night of January 24-25, as fascist troops entered the outskirts of the city, Capa photographed Gallagher (below) and Herbert Matthews preparing and telephoning their last dispatches (by candlelight, since the fascists had cut the power lines) before the three of them left the beleaguered city together to drive north to the French border and safety.

In any case, it is possible to document Capa’s travels in Spain between the outbreak of the civil war and the first publication of his photograph; he was never anywhere within several hundred miles of San Sebastián. Gallagher probably did share a room near San Sebastián with a photographer who made pictures of posed exercises, but that photographer was certainly not Capa. Nearly forty years after the events, Gallagher’s memory had clearly played a trick on him. No doubt in perfectly good faith he confused Capa with someone else with whom he had shared a hotel room there in 1936. There is no evidence that Gallagher and Capa ever met before January 1939, when they were both staying in the Hotel Majestic in Barcelona. On the night of January 24-25, as fascist troops entered the outskirts of the city, Capa photographed Gallagher (below) and Herbert Matthews preparing and telephoning their last dispatches (by candlelight, since the fascists had cut the power lines) before the three of them left the beleaguered city together to drive north to the French border and safety.

That a lapse of memory like Gallagher’s is possible, and even expectable, was dramatically demonstrated to me while I was conducting interviews for my biography of Capa. When I interviewed (by phone) cartoonist Bill Mauldin, whose vigor inspired my confidence in his perfect recall, he told me that he had been with Capa on the Roer river front in the spring of 1945. I told him that I was surprised to hear that, for I was quite certain that Capa had been somewhere else at that time. Mauldin assailed my doubts by assuring me that he remembered so clearly being with Capa that he could even describe the photographs Capa made on the Roer front, which were published in Life. His descriptions were so precise that I recognized the photographs instantly when I looked them up in the magazine. They had, however, been made by George Silk, not by Capa, who was then covering the paratroopers who jumped east of the Rhine.

In his book The Spanish Cockpit (London, 1937), Swiss journalist Franz Borkenau tells that he witnessed a battle around the village of Cerro Muriano, eight miles north of Córdoba, on the afternoon of September 5, 1936. He says that he was accompanied by two photographers from the French illustrated magazine Vu ,but he does not give their names. In fact, they were Hans Namuth, who had known Capa in Paris before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and his friend Georg Reisner.

In his book The Spanish Cockpit (London, 1937), Swiss journalist Franz Borkenau tells that he witnessed a battle around the village of Cerro Muriano, eight miles north of Córdoba, on the afternoon of September 5, 1936. He says that he was accompanied by two photographers from the French illustrated magazine Vu ,but he does not give their names. In fact, they were Hans Namuth, who had known Capa in Paris before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and his friend Georg Reisner.

That afternoon Namuth and Reisner photographed the terror-stricken inhabitants of the village as they were fleeing a fascist air raid. When I interviewed Namuth, he told me that he had not seen Capa and Taro in Cerro Muriano. But when Vu, in its issue of September 23, 1936, published (on the page facing Capa’s Falling Soldier) Capa’s photographs of some of the same people that Namuth and Reisner had photographed along the same road outside Cerro Muriano, Namuth realized that Capa had been there that day.

That fact provided the essential clue for pinpointing where Capa photographed The Falling Soldier. On the vintage prints preserved in the files of Capa’s estate with their original chronological numbering written on the back, the numbers of the sequence to which The Falling Soldier belongs immediately precede those of the Cerro Muriano refugee series. Since I had found that the numbering on those vintage prints from Capa’s first trip to Spain closely conformed to the chronology that I had established from other documentation, I concluded that Capa photographed The Falling Soldier during the battle at Cerro Muriano, on September 5, 1936.

Alas, the controversy raged on — with a superabundance of hot tempers and a dearth of objective analysis or research — until a fantastic breakthrough occurred in August 1996, when Rita Grosvenor, a British journalist based in Spain, wrote an article about a Spaniard, named Mario Brotóns Jordá, who had identified the Falling Soldier as Federico Borrell García and had confirmed in the Spanish government’s archives that Borrell had been killed in battle at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936.

The story of how Brotóns made his discovery is a fascinating one. Born in the village of Alcoy, near the city of Alicante, in southeastern Spain, Brotóns had himself joined the local Loyalist militia, the Columna Alcoyana, at the age of fourteen — and was himself a combattant in the battle against the Francoist forces under General Varela that took place on and around the hill known as La Loma de las Malagueñas at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936. When Brotóns’s friend Ricard Bañó, a young Alcoy historian, mentioned to him that he had read (in my biography of Capa) that Capa’s photograph might have been made during the battle at Cerro Muriano, Brotóns began his research. He knew that the man in the photograph must have belonged to the militia regiment from Alcoy, for the distinctive cartridge cases the man is wearing had been specially designed by the commander of the Columna Alcoyana and made by the leather craftsmen in Alcoy. No one in any of the other Loyalist militia units participating in the battle at Cerro Muriano would have worn such cartridge cases.

Because Brotóns had himself fought at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936, he remembered from his first-hand knowledge that Federico Borrell García had been killed there that day. In the course of his research, Brotóns contacted the historian Francisco Moreno Gómez (author of the definitive book about the civil war on the Córdoba front), who informed him that the records in the Spanish government archives in Salamanca and Madrid confirm that only one member of the Columna Alcoyana died at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936. Brotóns then could be certain that the man in Capa’s photograph must be Federico Borrell García. When Brotóns showed Capa’s photograph to Federico’s younger brother, Everisto, he confirmed the identification.

In his self-published book, Retazos de una época de inquietudes,Brotóns tells the story of the Alcoy regiment in Andalusía during September 1936. He recounts that Borrell, a 24-year-old millworker from Alcoy, was one of about fifty militiamen who had arrived at Cerro Muriano on the morning of September 5 to reinforce the Columna Alcoyana’s front line. That afternoon he was defending the artillery battery in the rearguard of the Alcoy infantry when enemy troops infiltrated behind the Loyalist lines and began firing at them from behind as well as from in front, hoping to squeeze the Loyalists in a vise. It was about five o’clock when Borrell was fatally shot. That time accords with the long shadows in Capa’s photograph.

In July 1998, at the time of a Robert Capa retrospective exhibition in London, Phillip Knightley came out with an article dismissing Brotóns’s discovery and stating, “The famous photograph is almost certainly a fake — Capa posed it.” He goes on to argue fatuously, “Federico could have posed for the photograph before he was killed.”

To provide a definitive refutation of Knightley’s absurd suggestion, that “Federico could have posed for the photograph before he was killed,” I turned to an expert whom I had met when I accompanied Cornell Capa to the University of Memphis, Tennessee, where Cornell gave a master class that was open not only to university students but also to qualified members of the public. One of the latter was Captain Robert L. Franks, the chief homicide detective of the Memphis Police Department and a talented sculptor and photographer. We had renewed our acquaintance several times on Capt. Franks’s visits to New York with groups from the university’s photography department. When I asked him, in September 2000, whether he would be willing to give me a reading of the two `moment of death’ photographs as if they were evidence in a murder case, he very kindly acceded to my request.

To provide a definitive refutation of Knightley’s absurd suggestion, that “Federico could have posed for the photograph before he was killed,” I turned to an expert whom I had met when I accompanied Cornell Capa to the University of Memphis, Tennessee, where Cornell gave a master class that was open not only to university students but also to qualified members of the public. One of the latter was Captain Robert L. Franks, the chief homicide detective of the Memphis Police Department and a talented sculptor and photographer. We had renewed our acquaintance several times on Capt. Franks’s visits to New York with groups from the university’s photography department. When I asked him, in September 2000, whether he would be willing to give me a reading of the two `moment of death’ photographs as if they were evidence in a murder case, he very kindly acceded to my request.

The most decisive element in his reading is the soldier’s left hand, seen below his horizontal left thigh. Capt. Franks told me in conversation that the fact that the fingers are somewhat curled toward the palm clearly indicates that the man’s muscles have gone limp and that he is already dead. Hardly anyone faking death would ever know that such a hand position was necessary in order to make the photograph realistic. It is nearly impossible for any conscious person to resist the reflex impulse to brace his fall by flexing his hand strongly backward at the wrist and extending his fingers out straight.

Taking all of the available information into consideration, I shall now put forward my hypothesis of Robert Capa’s experience on the afternoon of September 5, 1936, during the battle between various Loyalist militias and the Francoist forces led by General Varela.

Taking all of the available information into consideration, I shall now put forward my hypothesis of Robert Capa’s experience on the afternoon of September 5, 1936, during the battle between various Loyalist militias and the Francoist forces led by General Varela.

across a shallow gully and hugged the ground at the top of its Capa encountered a group of militiamen (and at least one militia-woman) from several units — Francisco Borrell García among them — in what was at that moment a quiet sector. Having decided to play around a bit for the benefit of Capa’s camera, the men began by standing in a line and brandishing their rifles. Then, with Capa running beside them, they jumped to the far side, aiming and firing their rifles — thereby, presumably, attracting the enemy’s attention. I have always assumed that they next continued their forward advance, running down the exposed hillside. I now realize that that assumption is incorrect. What actually must have happened is that at least a couple of the men — including Borrell — turned around and climbed back up the side of the gully that was behind them when they pretended to fire. In Capa’s two photographs of the soldiers crossing the gully, we can clearly see, in the upper left corner of each picture, upstanding stalks of grass like those underfoot in the two `moment of death’ photographs.

Once Borrell had climbed out of the gully, he evidently stood up, back no more than a pace or two from the edge of the gully and facing down the hillside, so that Capa (who had remained in the gully) could photograph him. Just as Capa was about to press his shutter release, a hidden enemy machinegun opened fire. Borrell, hit in the head or heart, died instantly and went limp while still on his feet, as Capa’s photograph shows. As soon as he had fallen to the ground, comrades must have dragged his body immediately back into the gully. That would explain why his corpse is not visible in the other picture. Indeed, Capt. Franks concluded that the Falling Soldier was the first to be shot. He wrote, “I base this upon the cloud formation that seems to be tighter in [The Falling Soldier] and more dissipated in the [other] picture. The second soldier’s photograph is in focus, which indicates to me that Robert Capa had time to attend to the settings on his camera between the two shots.” wor Capa — presumably with at least a few of the militiapersons — must have remained safely in the gully until the coast was sufficiently clear to allow a return to the village. It is not known whether they carried with them the bodies of the dead or abandonned them on the hillside. In either case, Federico’s body was not returned to Alcoy for a proper funeral and burial.

Once Borrell had climbed out of the gully, he evidently stood up, back no more than a pace or two from the edge of the gully and facing down the hillside, so that Capa (who had remained in the gully) could photograph him. Just as Capa was about to press his shutter release, a hidden enemy machinegun opened fire. Borrell, hit in the head or heart, died instantly and went limp while still on his feet, as Capa’s photograph shows. As soon as he had fallen to the ground, comrades must have dragged his body immediately back into the gully. That would explain why his corpse is not visible in the other picture. Indeed, Capt. Franks concluded that the Falling Soldier was the first to be shot. He wrote, “I base this upon the cloud formation that seems to be tighter in [The Falling Soldier] and more dissipated in the [other] picture. The second soldier’s photograph is in focus, which indicates to me that Robert Capa had time to attend to the settings on his camera between the two shots.” wor Capa — presumably with at least a few of the militiapersons — must have remained safely in the gully until the coast was sufficiently clear to allow a return to the village. It is not known whether they carried with them the bodies of the dead or abandonned them on the hillside. In either case, Federico’s body was not returned to Alcoy for a proper funeral and burial.

The arrow indicates where Federico Borrell García was standing when he was shot; the X indicates where Capa was hugging the side of the gully.

The arrow indicates where Federico Borrell García was standing when he was shot; the X indicates where Capa was hugging the side of the gully.

There can be no further doubt that The Falling Soldier is a photograph of Federico Borrell García at the moment of his death during the battle at Cerro Muriano on September 5, 1936. May the slanderous controversy that has plagued Robert Capa’s reputation for more than twenty-five years now, at last, come to an end with a verdict decisively in favor of Capa’s integrity. It is time to let both Capa and Borrell rest in peace, and to acclaim The Falling Soldier once again as an unquestioned masterpiece of photojournalism and as perhaps the greatest war photograph ever made.

by Richard Whelan

Copyright © 2002 by Richard Whelan

Robert Capa photographs copyright © 2001 by Cornell Capa

Another version of this article appeared in APERTURE magazine, No. 166, Spring 2002

FURTHER READING

Borkenau, Franz. The Spanish Cockpit.London: Faber & Faber, 1937.

Brotóns Jordá, Mario. Retazos de una época de inquietudes,second edition. Alcoy: self-published, 1995.

Capa, Cornell, and Richard Whelan, eds. Robert Capa: Photographs.New York: Aperture, 1996.

Heart of Spain: Robert Capa’s Photographs of the Spanish Civil War.Catalogue ofan exhibition organized by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; with essays by Catherine Coleman, Juan P. Fusi Aizpúrua, and Richard Whelan. New York: Aperture, 1999.

Knightley, Philip. The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam; The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth Maker.New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1975.

Levinski, Jorge. The Camera at War: A History of War Photography from 1848 to the Present Day. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978.

Whelan, Richard. Robert Capa: A Biography.New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985; London: Faber & Faber, 1985. Paperback edition published 1994 by University of Nebraska Press, 1994, and still in print.